On June 8, two days before our interview, David Byrne surprised the crowd by getting onstage during Olivia Rodrigo’s set at the Governors Ball in New York. The two performed Burning Down the House, a single he released with his band Talking Heads in 1983. Both singers wore red overalls and white T-shirts as they made their way through choreography inspired by Byrne’s own moves in the film Stop Making Sense (1984), a recording of the band’s tour directed by Jonathan Demme, considered one of the creative peaks of popular music in the second half of the 20th century, and which, after being remastered, returned to theaters last year.

Rodrigo would spend the rest of the summer inviting her other musical heroes to the stage, including Robert Smith and Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo, but the only one with whom she had a matching outfit and dance routine was Byrne.

Such singularity has marked the 73-year-old artist’s career ever since the first time he picked up a guitar alongside his classmates from the Rhode Island School of Design. A constant search for the next step, continuing to gaze when everyone else thinks they’ve seen it all, saying something when everything seems to have already been said.

Talking Heads was one of the bands that took shape in the era of New York’s East Village club CBGB. Byrne, Tina Weymouth, Jerry Harrison and Chris Frantz were going for a vibe that was a little punk, like their neighbors the Ramones and Richard Hell & The Voidoids, until one day in the dressing room, Lou Reed told them that they, unlike the others, didn’t have to play so fast.

The group took his advice and became one of the most important creative forces of the late 1970s and 1980s. They sold 30 million albums, but never played a stadium show. In 1991 the band broke up, leaving behind an immeasurable legacy in which punk and pop blend with Latin and African sounds, experimental electronica and performance art. Few bands have been at once so intelligent and so fun.

“Well, technically we haven’t broken up,” clarifies Byrne, who showed up to his interview in a London hotel in the same clothes he wore to perform with Rodrigo in New York. He lets out a chuckle that lands somewhere between mischievous and shy, the likes of which reappear various times throughout the chat, usually denoting a moment in which he is very pleased with what he’s said, or unsure about what he’s about to say.

“I never called them to say it,” he continues, confirming that the group’s separation was as bitter as it was expected, to the point that he saw no reason to make it official internally.

Talking Heads is, along with The Smiths, one of the era’s only major bands that never returned to the stage after its breakup. And Byrne, allergic to nostalgia, is responsible for that. It’s rumored that the last offer to reunite with the group with which he recorded Remain in Light with Brian Eno in 1982 was extended just a year ago, and that the amount on the table was $80 million.

In 2010, Byrne published the book ‘Bicycle Diaries’, a reflection on mobility.Manuel Vázquez

In 2010, Byrne published the book ‘Bicycle Diaries’, a reflection on mobility.Manuel Vázquez

Today, Byrne is in London to promote his new solo album, Who Is the Sky? The title comes from a voice message that was misunderstood by Siri, and is an optimistic and organic celebration full of wind instruments, acoustic guitars and crystalline melodies. It is the work of someone happy who is still capable of producing strong songs without plagiarizing themself, and of being current without chasing any trend.

The album came out on September 5 and was produced by Kid Harpoon (Florence Welch, Harry Styles). It features collaborations with artists like St. Vincent, with whom he recorded the album Love This Giant in 2012, which perhaps brought him back into the spotlight in the only way he finds truly fulfilling: with new songs that tell new stories and sound fresh.

Then came American Utopia (2018), nominated for a Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album, which would later become a Broadway musical full of the movement and positivity that defines the current era in which Byrne finds himself.

The success of American Utopia was followed by the 2023 re-release of Stop Making Sense and an album in which contemporary artists like Paramore and Miley Cyrus covered Talking Heads songs, introducing his music to a new generation of listeners without needing to go viral on TikTok.

Byrne sips water in the hotel, located a few feet rom Hyde Park. “I’m in style,” he says. And laughs.

Question. You wrote a book titled How Music Works, and it really does explain that. But why do you make music? Are you as clear on that subjet?

Answer. I think, to feel okay. It’s not always easy to feel okay, because I read the press and the news today doesn’t make you feel happy or hopeful. I think that I make this music as an act of resistance, as a counterweight to what I read in the press. It’s not entirely conscious, it involves a lot of intuition. I don’t sit down and say to myself, “I’m going to write something positive, a pretty song.” But if I put out something like that, without being sentimental or simplistic, it makes me feel good, it helps me and I think sometimes, it can help others too.

Q. How has music helped you?

A. I try to understand the world and people through songs. Someone once said that I was an anthropologist from Mars and I liked that idea. I pose questions all the time. Why do people fall in love? Why do they do that? Why do I do that? A lot of the time, I make music just for myself.

Q. The album is a call for empathy and collective and communal feeling. Has that been lost? Has individualism conquered all?

A. Without a doubt. Perhaps not everywhere, but where I live, that’s exactly what it’s like. And it’s been like that for many years. It is a gradual erosion of the sense of community and of empathy. This idea of being like, a separate entity from everything that surrounds us is relatively new. It’s not entirely wrong, but if you take it to the extreme, which is what is happening, it becomes something very painful and damaging to the survival of the species.

Talking Heads performance in the 1980s.Richard E. Aaron (Redferns/Getty)

Talking Heads performance in the 1980s.Richard E. Aaron (Redferns/Getty)

Q. Does that individualism lead many to end up believing that there are as many truths as people, with all the risks that implies?

A. That is terrible. When everyone says, “This is my truth, I made it, it belongs to me.” That is terrible and obviously false. I don’t know where that comes from. I think that more and more, the idea of an individual being is a fallacy. We are ever-changing. We exist in relationship with that which surrounds us. This idea that everything we are and that which we believe in comes from us is false.

Q. What musical profile would you have if you were beginning your career today? What seems clear is that you’d be going solo from the very start.

A. Clearly [laughs]. Yes, yes [more laughter, takes a sip of water, pauses]. Nowadays you can do everything at home with your computer. Young people are doing that and they’re happy. Right now, everything is more complicated economically, making money from your recordings is getting more and more difficult. Musicians have to be small businesses, sell shirts, diversify, be focused on the bottom line. It seems like there is more innovation now in the music that I hear than in the past. A lot of current music doesn’t fit into any category and that is wonderful.

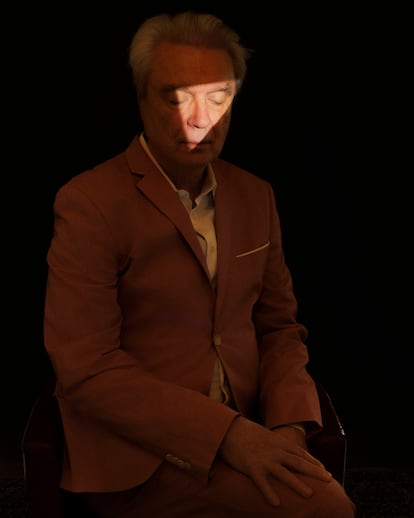

David Byrne, pictured in June in London. His new solo album, ‘Who Is the Sky?’, was released on September 5.Manuel Vázquez

David Byrne, pictured in June in London. His new solo album, ‘Who Is the Sky?’, was released on September 5.Manuel Vázquez

Q. One of your priorities when you started Talking Heads was that the way you moved on stage wouldn’t be like anyone else. That quest to be unique is a constant in your career. Does it overcomplicate things for you?

A. [Laughs] Too much so, yes. It’s true… when I got started as an artist, I was watching Mick Jagger, James Brown, incredible people. I was seeing other musicians from my generation try to imitate them and I thought, why are they doing that? They already exist, and doing it brilliantly. Look for your own path. I thought that it was possible to find your own language through your movements. Little by little, I wrote my story and now I’m known for really crazy moves that I thought up. It’s fascinating [laughs]. I have to maintain that idea of reinventing myself, keeping the good and seeing what I can add to the nonsense I do onstage. I have to re-imagine what makes an artist. For example, I can’t return to the idea of us all being still onstage. I want to maintain that sense of movement. Make it so that the idea also moves. I’m not sure if I’m explaining myself.

Since the dissolution of Talking Heads in 1991, Byrne has put out eight albums, both solo and in collaboration with musicians like Brian Eno and St. Vincent.Manuel Vázquez

Since the dissolution of Talking Heads in 1991, Byrne has put out eight albums, both solo and in collaboration with musicians like Brian Eno and St. Vincent.Manuel Vázquez

Q. Up to what point does going onstage help you to break with your eternal shyness?

A. I didn’t use to think about that, it was all compulsive. I only wanted to go out onstage and express myself. That was enough for me. It took a lot for me to relate to other people, so I convinced myself that onstage I was anonymous and from that anonymity, I could do whatever I wanted. Then, after I came offstage, I could go back into my shell. Now, it’s easier for me to talk to people. I discovered that if I could express myself on the stage, perhaps I could also try to communicate off of it. The precedent for that dates back to my high school years. I ran for election as a class officer without being able to talk to anyone. One always looks for solutions.

David Byrne, photographed on the eve of his new solo album release in London.Manuel Vázquez

David Byrne, photographed on the eve of his new solo album release in London.Manuel Vázquez

Q. Is art the search for solutions?

A. For me it is. It’s essential. Sometimes there are people who help us and show us the way, or lend us a hand, but on other occasions, we have to discover it for ourselves, because what is important to us isn’t always important to everyone else. I understood that not everyone is like me, what can you do? [Laughs]. Sometimes, you also see that in politics: there are people who have not fixed their own problems and all they do is dump them onto us. They haven’t gotten it together, and the rest of us are paying for it.

David Byrne, former frontman of Talking Heads.Manuel Vázquez

David Byrne, former frontman of Talking Heads.Manuel Vázquez

In 1988, Byrne won an Oscar with Ryuichi Sakamoto for the soundtrack to the Bernardo Bertolucci film The Last Emperor. At the time,his mind and concerns were drifting further and further away from his work as the frontperson for Talking Heads.

After releasing the organic and moderately rock-oriented True Stories album in 1986 — the kind of record any established band was expected to make in the latter half of the 1980s — the group put out its last album, Naked, in 1988, an almost tropicalist project that heralded its end and the beginning of Byrne’s solo career. The artist had already worked on side projects with Brian Eno, but it was in the 1990s that he began to more deeply explore Latin and African rhythms. The journey led him to collaborate with Peret and Caetano Veloso.

At the end of the decade, Byrne was feeling penned-in by music. He conducted his process of seeking out new forms of creation by bicycle, and in the 2000s, became a fervent advocate of the urban cycling movement. He published a book, Bicycle Diaries (2010), on his experience of pedaling through half the world’s major cities and his reflections on mobility issues. He designed bicycle racks, and returned to visual arts and photography, even discovering in PowerPoint a medium for creating art.

In 2013, he published How Music Works, an impressive treatise on music and creativity. He launched Reasons to Be Cheerful, a website about innovation and positivity that despite the current state of the world, remains active. He was invited to run for the mayor of New York City. He said no. A journalist came to his studio and asked where he kept his Oscar. “No idea,” he responded.

Question. Has music always been the way you best express yourself?

Answer. The truth is that at first, I didn’t realize it, I didn’t consider music to be something that could channel my artistic intentions. I tried to study something related to science and technology, I thought there was space for creativity there. For a time, science was art to me. In art school you have to be creative in the moment, while in science, you spend years accumulating knowledge before you can be. And I told myself: I want this to happen now. So I studied art, but never music. A lot of punks went to music school and learned techniques and theories and I also thought I wanted to know about those things. But I saw how some of my friends have later tried to forget those lessons, which were dogmatic and classicist. At any rate, my idea when I got to New York was to be a visual artist — I didn’t think I had any talent for music, that was something to play at with my friends. We didn’t take ourselves seriously. Some time ago, I read a book by Fernando Trueba in which he says that many directors put out their best films when they’re not taking themselves seriously, with little intention, but a lot of play. The only way to create a masterpiece is by not trying to create a masterpiece.

Q. What are you like to work with?

A. I try to make it so that everyone is part of the process, but it hasn’t always been like that. As a young person, I was a dictator: this is what I want and this is what is going to happen. Sometimes I was right, but the process wasn’t very pleasurable. Now, I can share my vision and the direction that I think we should take, making sure that everyone feels like part of the process. And if we all take the same path, all the better. I don’t force anyone to do anything. I have improved the way I collaborate.

Q. Have you improved your social skills?

A. Now I can talk to people.

Q. Between the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, you took an interest in and started collaborating with Brazilian and African artists from what at the time was called “world music.” Do you feel that in a certain way, you helped to perpetuate colonialist stereotypes?

A. “World music” seems like an us versus them label. And the truth is, we Americans are not separate from the world. We’re part of a world that we sometimes struggle to understand isn’t ours. That term still exists, but even back then it was beginning to change. In the United States, people began to appreciate certain artists, Brazilians like Caetano Veloso, Mexicans like Selena. That managed to individualize them, because before, everything was Brazilian music, African music…

Byrne, during a concert in Oxford in 2018.Jim Dyson (Getty Images)

Byrne, during a concert in Oxford in 2018.Jim Dyson (Getty Images)

Q. Did you feel like a tourist?

A. I remember when, many years ago, I was on tour with the Latin band — people in Mexico, Brazil and Argentina liked what we were doing. The rhythms were familiar to them, it was their parents’ music. And there I was, this punk guy saying that he really liked his parents’ music, that it shouldn’t be forgotten, that it was very good. I think that they felt like I was truly interested, but it is true that I was a tourist, I’m not going to deny it. I said all the time, “What is that? Tell me, what do I need to know? How do you do it?” I asked a lot of questions. They understood it was sincere. I remember that in Argentina, I met León Gieco. He started out as a rock ‘n’ roller, and began incorporating folkloric elements to his music. One day he said, “Do you want to meet Mercedes Sosa?” We went to her apartment and it was like meeting the queen. A wonderful experience. Meanwhile, in the United States what I was doing was seen as a betrayal.

Q. Is the domination of English-language music coming to an end?

A. I think so. Some of these Spanish-speaking and African artists are very successful. Although, many still believe that they have to leave their countries and work in Europe or the United States to achieve international success. The big change will arrive when the musical ecology of those countries supports local talent to become stronger globally. In music and other art forms, it’s not enough to be a great artist, you need a system to support that.

Q. You always said that you were a functional and undiagnosed autistic at a time that those kind of confessions weren’t common. Times have changed and those subjects are more talked-about. How do you experience that?

A. Many young people who I have met these days are very on top of that. At a certain point, social media and all that absorbed them and they wound up talking about the subject in their songs. They speak openly about the false necessity of always having to be sharing your life, comparing yourself with others, suffering anxiety over what others are thinking about you. They write about that and it’s good that they’re doing it. They heal themselves through their songs.

Q. Up to what point have you revisited your past and found things you’re ashamed of?

A. [Laughs] A few years ago, I remembered that I made a promotional video for Stop Making Sense. It had a lot of characters responding to things in the film, and one of them was Black. I painted my face black. No one has said anything to me about it in years, even though it’s been on YouTube. But I thought I should confess: look, I did this and I won’t do it again. It was many years ago and there was no malicious intent. Many people told me it was OK, that it was understandable. But others saw it and said, “David, we can’t work with you anymore.” I was canceled in several places. I remember I was working with Spike Lee at the time and I told him, “Spike, you should know I did this.” He said, “David, I’ve known you for years, don’t worry.”

Q. You have always been a big fan of technology. Have we been too enthusiastic with all this progress? Have we been assuming that it is something inherently positive when it isn’t always?

A. Like many others, I have seen these cycles in which the world of technology appears and says that they’ve got it, that they are going to put an end to all problems, that it is going to connect us, even that it will fix democracy. That is almost never true. Plus, the intentions of the people running the world are not so clear, or generous. They just want to make money. I think that ultimately, people don’t trust the world of technology as much anymore. It’s gotten complicated. Before I took the flight here, I had breakfast at the airport in New York, in a restaurant. It’s one of those where there is only one person who tells you if you sit here or there. The menu is a code and you put your telephone on it and you insert your card. A nightmare. But I managed to do it. It took me much more time than if I had talked to a person. You can’t order anything different, none of that. An older man sat next to me. He had no idea what to do. I tried to help him, but he got fed up and left. Another couple came, started to do the process, but they also got fed up and left. That’s not very good for the business. Sometimes they adapt these technologies to save money and they don’t realize that they’re losing customers because it’s kind of cold and alienating. Customers hate it. You can’t reduce everything to what’s practical.

The musician attends the interview wearing the red jumpsuit he had worn two days earlier at a concert with Olivia Rodrigo in New York.Manuel Vázquez

The musician attends the interview wearing the red jumpsuit he had worn two days earlier at a concert with Olivia Rodrigo in New York.Manuel Vázquez

Q. What is it like being an American of your fame abroad, given the current climate and the person in the Oval Office?

A. [Laughs] Wow. Sometimes I feel like we have to explain ourselves. A lot of people come and ask you, “What happened?” Well, it’s not just happening in the United States, but of course, our case is very crazy. The explanation is not something you can unlock in one sentence, it goes back many decades. Perceptions have been changing for some time. Many economic decisions have been made that affect the way people see things, which sometimes isn’t real. But feelings matter more than facts. There are a lot of people who have more money than they think, but they feel like they don’t. And at the end, that makes the difference.

Q. How did it feel doing promo with the members of Talking Heads for the premiere of the new version of Stop Making Sense?

A. For the most part, it was wonderful. We are all still so proud of it. And it wasn’t just the older fans who went to the theaters, there were a lot of young people. I liked that.

Q. Were you prepared for that press cycle to revive rumors about the band’s return?

A. I’m aware of all those rumors. I think that for a lot of people who heard that music at a time in their life, it means a lot, they want to recover that connection. But it’s impossible, it wouldn’t be the same. It’s nice when you see a band like Pulp, which is getting back together now, playing in much bigger venues than the ones it played in the 1990s. Maybe now they’re earning the money they deserved back then. In that case, getting back together makes sense. In ours, it doesn’t.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition