A commercial freighter that ran aground in the Northwest Passage earlier this month is the latest in a string of Arctic shipping incidents where experts say luck prevented a worse outcome.

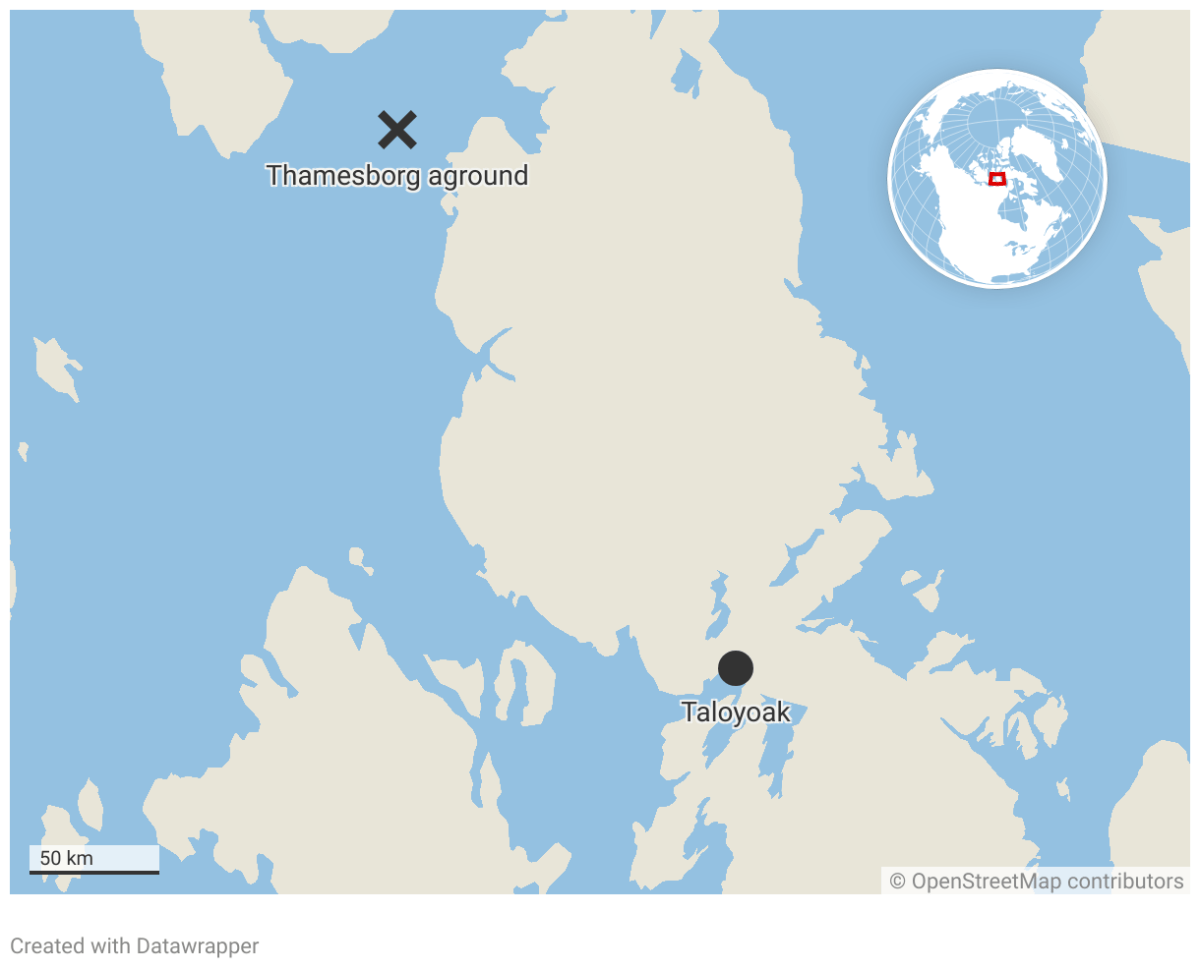

On September 6, the Dutch-owned cargo ship MV Thamesborg was transporting industrial carbon blocks from China to Quebec when it hit a shoal in the Franklin Strait, which lies between Prince of Wales Island and the Nunavut mainland.

Another commercial vessel was soon directed to the scene, followed by two Canadian Coast Guard icebreakers.

A Canadian Coast Guard ship, left, alongside the Thamesborg in the Northwest Passage. Photo: Canadian Coast Guard

A Canadian Coast Guard ship, left, alongside the Thamesborg in the Northwest Passage. Photo: Canadian Coast Guard

None of the 16 people on board were injured, and no cargo or fuel was spilled into the environment according to the Wagenborg, the ship’s owner, and the Canadian Coast Guard. An assessment by the crew revealed damage to the hull and flooding in multiple ballast tanks.

The vessel is still stranded. A draft salvage plan submitted by the ship’s owner is being reviewed by authorities, the coast guard said last week.

Everything seems to have unfolded as best it could, says Suzanne Lalonde, a professor of public international law and law of the sea at the Université de Montréal.

“It feels like this is another instance we’ve been lucky,” she says, adding there are still many unknowns about the circumstances surrounding the grounding.

It’s not the first time a ship has been grounded in the Canadian Arctic, nor the most dramatic case in recent history.

In 2010, the expedition cruise ship Clipper Adventurer ran aground on a shoal about 100 km from Kugluktuk. After roughly two days, the ship’s 128 passengers and 69 crew had to be brought to Kugluktuk and flown south.

Similarly, in 2018, the research vessel Akademik Ioffe grounded on a rocky shoal about 145 km northwest of Kugaaruk. The ship’s 163 passengers and crew were transferred to the Ioffe’s sister vessel and 81 litres of fuel oil were spilled into the sea.

There have been close calls for larger spills, too.

The fuel tanker MV Nanny ran aground three separate times between 2010 and 2014. In one instance, the ship was stuck on a sandbar for nearly two weeks with 9.5 million litres of diesel on board.

According to Lalonde, while people often say melting sea ice is making the Northwest Passage more viable, incidents such as the Thamesborg grounding highlight challenges that still exist in the area.

“It’s not an easy route,” she says.

Only a fraction of Arctic waters have been mapped to modern standards, ice and weather conditions are challenging and increasingly hard to predict in a changing climate, and when something goes wrong, help is often far away.

With shipping traffic in the region expected to keep growing, more incidents and groundings are likely, according to Jackie Dawson, Canada Research Chair in environment, society and policy at the University of Ottawa, who studies Arctic shipping and climate change.

“I think this situation is fairly under control,” she says. But, she adds, “it’s just a matter of time before these close calls become more disastrous.”

Climate change creates challenges for shipping

The Northwest Passage refers to a handful of routes connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans along the northern coasts of the United States and Canada.

As sea ice declines, interest in these routes is growing, as they have potential to become a shorter and cheaper alternative for ships travelling between Europe and Asia.

Warming has caused a drastic loss of sea ice in recent decades. Since 1979, Arctic sea ice extent has shrunk by more than 40 percent during late summer, and what’s left is thinner and more fragile.

Meanwhile, shipping traffic in the Arctic is increasing. The number of voyages undertaken in the Canadian Arctic has quadrupled since 1990.

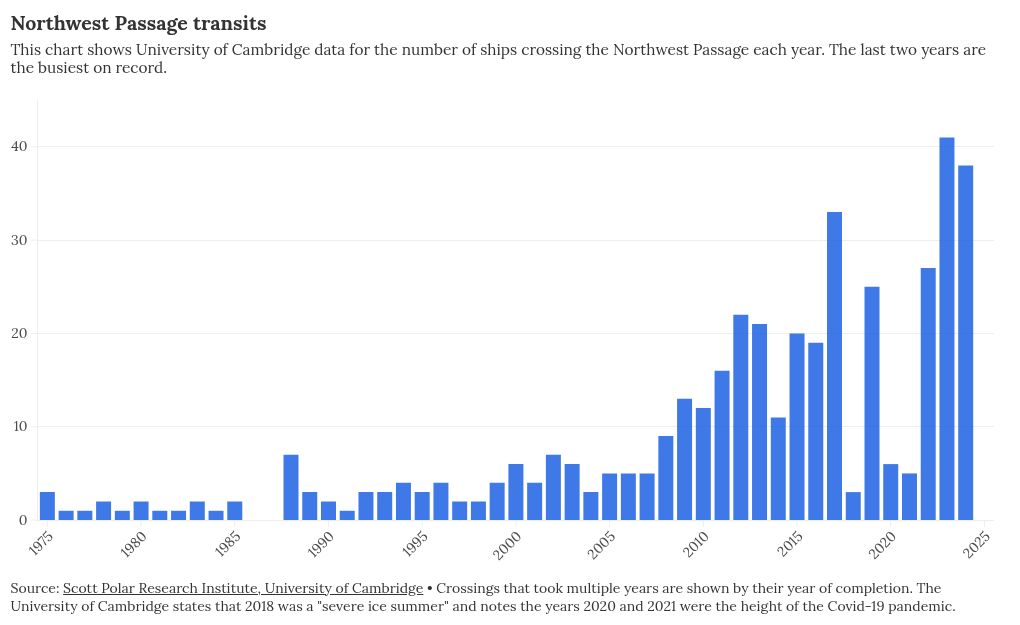

Traffic transiting the Northwest Passage has also seen a significant rise. Up until the late 1980s, less than three ships transited the route per year. In the past few years, roughly 40 ships have traversed the Northwest Passage annually, according to a 2025 report from the University of Cambridge. (This number does not include trips within but not through the passage, which “have become too numerous to record” using their tracking method, the report’s authors wrote.)

The general assumption is that the Northwest Passage will become easier to navigate as sea ice melts, but the reality is murkier.

As the planet heats up, large sheets of ice are breaking up into smaller pieces that flow southward and create choke points. In a 2024 study, Dawson and her colleagues found that despite a reduction in sea ice cover, the overall length of the shipping season actually declined from 2007 to 2021 because of this.

“The Franklin Strait is one of the areas where we often see choke points,” she says, adding that pile-ups of ice can push ships into slightly uncertain and uncharted waters.

In another 2024 study, Dawson and her colleagues found that sea ice concentrations were significantly correlated to shipping accident rates. This mobile ice, combined with windier and wavier conditions expected in a changing climate, creates challenges for ships.

Dawson says she isn’t surprised by the Thamesborg grounding, having heard from her students and colleagues on ships in the Arctic that ice conditions were particularly challenging this summer.

“Most of the vessels didn’t make it through,” she says. “There have been many groundings this year. It’s just that we only hear about the ones that can’t self-rescue.”

At least one other cargo vessel was reported to have run aground in Pelly Bay, near Kugaaruk, on August 23.

There are still a lot of questions about the circumstances around the Thamesborg’s grounding.

Survey data for the area is not up to modern standards, as Eye on the Arctic previously reported, but the shoal the ship hit was shown on navigational charts and guides.

Wagenborg is also fairly experienced in transiting the Northwest Passage, according to Brian Tattuinee, business development manager at Nunavut Sealink and Supply Inc, which operates ships throughout the Canadian Arctic.

Authorities are still investigating what went wrong.

Ship grounded in proposed protected area

The nearest community to the grounding is Taloyoak, in Nunavut.

The incident is “very upsetting,” says Jimmy Ullikatalik, manager of the Taloyoak Umaruliririgut Association.

The site of the grounding is within Aqviqtuuq, a proposed Inuit Protected and Conserved Area that encompasses upward of 90,000 sq km of land and waters around the community.

Protecting the area, which is rich in wildlife, is critical to residents.

“We are hunters and gatherers, fishers,” Ullikatalik says. “That means our wildlife is our food.”

His main concern is an oil spill, which would destroy the marine ecosystem. But increased shipping traffic is already disrupting the region’s wildlife and the community’s ability to harvest.

This year’s community hunt was disturbed by ships, according to Ullikatalik. Because there was too much traffic in the area, belugas wouldn’t go into the shallow waters where they typically go to shed their skins.

“Every year, we get requests for ships to go through the Northwest Passage,” Ullikatalik says. “We never, ever approve any of them. But yet, there’s still so much traffic.”

Through the establishment of Aqviqtuuq, which is targeted for 2030, the community hopes to gain more control over ships coming through the area. Specifically, Ullikatalik says, the community doesn’t want any ships in the area during the first two weeks of August.

Although the risk of a major spill is what immediately comes to mind with Arctic shipping, there are other consequences associated with ship traffic, according to Sam Davin, a senior specialist in marine conservation and shipping at WWF-Canada.

He says ship traffic brings noise pollution, water pollution from waste such as sewage and grey water, and air pollution from exhaust.

Ballast tanks can accumulate contaminants such as oil residues, rust and heavy metals, or carry invasive species.

While Davin said it’s good news that no fuel was spilled from the Thamesborg, the ship’s ruptured ballast tanks raise questions about what was in that ballast.

“There’s a lot of other ways a ship can pollute the environment that aren’t quite as dramatic [as a fuel spill] but are still really impactful,” he says.

According to Davin, the incident highlights that Canada is not ready for projected increases in Arctic shipping. Stronger regulations are needed, he added, to better manage pollution and address community concerns.

Preparing for a major disaster

Although challenging conditions in the Northwest Passage currently limit ship traffic, Dawson – the University of Ottawa Arctic shipping and climate change scientist – thinks we will see more commercial traffic in the not-too-distant future.

“The economics are enticing, the geopolitics have changed and, even though the ice is definitely not open, it’s certainly way more open than it used to be,” she says.

With increasing traffic come greater risks.

The freighter Thamesborg is seen in a file photo published by its operator, Wagenborg.

The freighter Thamesborg is seen in a file photo published by its operator, Wagenborg.

Martin Lougheed is the manager of environment and wildlife in the policy advancement department at Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, which represents Inuit in Canada.

Lougheed is concerned about the prospect of a major disaster.

“We’re not sure right now that we’re seeing enough action towards response to be able to meet the growing demand,” he says.

The Canadian Coast Guard is responsible for responding to vessels in distress in federal waterways, according to Peter Kikkert, associate professor in public policy and governance at St Francis Xavier University, who studies search and rescue in northern communities.

The military, working closely with the coast guard through the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre, is responsible for coordinating the response.

The marine search and rescue system also makes use of other vessels in the vicinity of an incident to assist. In the case of the Thamesborg, for instance, another commercial vessel was the first on scene.

One positive side effect of more ship traffic, according to Kikkert, is more ships can assist with search and rescue.

The federal government has also taken recent steps aimed at making Arctic shipping safer. Federal agencies and authorities have surveyed Arctic waters to improve navigational products, undertaken more rigorous training to prepare for a potential mass rescue, and built stronger relationships with territorial and community partners to improve coordination during emergencies.

According to Kikkert, there has also been a substantial effort to increase marine search and rescue capacity in the North.

In 2015, there were nine coast guard auxiliary units north of 60, only three of which functioned year-round. Now, Kikkert says, there are 41 units, with more than 500 members in the Arctic.

Depending on where a shipping incident occurs, these all-volunteer units might support search and rescue efforts by getting eyes on the situation, Kikkert says.

In an urgent situation, however, the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre would be responsible for deploying not only marine assets like icebreakers but also search and rescue aircraft and helicopters, which are all based in the south.

“It’s going to be hours and hours to get on scene,” Kikkert says.

While we are better prepared for shipping incidents than we have been in the recent past, he adds, any kind of rescue operation is still going to be an enormous test.

Kikkert describes incidents over the past 15 years as “warning shots.”

Each situation could have required a challenging response had we been a little less lucky, he says, adding the takeaway is we need to keep investing in Arctic search and rescue.

Lougheed, from ITK, echoed Kikkert, saying the Thamesborg incident could have easily been a disastrous scenario.

While he says there are risks with increased shipping, there are also potential benefits, such as more frequent resupply to communities.

Lougheed would like to see a bigger role for Inuit in managing shipping. Inuit need to be involved in discussions about planning shipping traffic and safe routes through the Northwest Passage, he says.

With communities like Taloyoak continuing to serve as first responders and logistics hubs when incidents occur, he adds, investment in community infrastructure is also urgently needed.

Related Articles