EDMONTON — On a Friday morning in January 2023, Alex Kearney, a research scientist at DeepMind Alberta, was checking her emails when she saw the bad news.

It was the day of her doctoral defence and parent company Google had just told staff that it planned to lay off 12,000 people. DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis warned Kearney and other staff at the AI unit that they’d see changes, too. Later that day, she celebrated her new PhD with colleagues from school and work. The following Monday, her dream job disappeared.

DeepMind Alberta, the firm’s first overseas office when it opened in July 2017, was shutting down. The news, a blip amidst a wave of tech industry layoffs at the time, was seen by many outside Edmonton as a major blow to the region’s AI ambitions.

Talking Points

In July 2017, when DeepMind opened its first overseas research lab in Edmonton, it was seen as recognition of Alberta’s AI expertise. In January 2023, when DeepMind closed its Alberta office, it was seen by some as a blow. Two and a half years later, Edmonton’s AI ecosystem is thriving.

Former researchers at DeepMind Alberta have launched startups like Artificial Agency and RL Core, which now employ more people between them than the Google AI lab ever did. Ex-staff are also advancing reinforcement learning techniques, which were pioneered in Edmonton, at industrial labs and research institutions in the city.

DeepMind had been a dream destination for students like Kearney working on reinforcement learning, a field of AI research that trains systems through trial and error. “I wanted to go to this place, DeepMind, and I wanted to work on solving intelligence,” she says. Now, DeepMind was ditching Alberta.

It wasn’t the first time the province’s AI community had faced doubters. Alberta has always taken its own path to solving intelligence. While other AI research centres focused on more logic-based methods or brain-like neural networks, many researchers at the University of Alberta’s computing science department worked on fringe disciplines like reinforcement learning. DeepMind’s arrival in Edmonton helped bring attention and acclaim to that unique strand of AI research. So its departure was taken as a blow.

Two and a half years later, Edmonton’s AI ecosystem is thriving. Researchers who stayed when DeepMind left are continuing to advance the science of reinforcement learning at UAlberta and at a new lab they’ve helped open. Other former staff have launched AI startups, like Kearney’s Artificial Agency. Still others are working on AI for multinationals like Sony. Meanwhile, a new cohort of students and researchers are dreaming different AI dreams.

Related Articles

By

Murad Hemmadi and Jesse Snyder

DeepMind’s arrival helped open up the horizons for AI in the Prairies, but so has its departure. Richard Sutton—the reinforcement learning sage who co-led DeepMind’s Alberta office—predicted this. The firm’s decision to exit Edmonton “is really worse for them than it is for us,” he told The Logic days after the decision was announced. “We are freed up,” he said, to “make new things.”

In the early 2000s, Edmonton was one of a few places in the world where deep networks of researchers were trying to make AI actually work.

UAlberta was “the best place in the world” for reinforcement learning, says Marc Bellemare, who left Montreal for Edmonton in 2007 to work on his PhD in the field.

At the time, reinforcement learning was known as “the discipline that doesn’t work,” Bellemare says. As a result, few AI researchers bothered with it. Sutton and some of the school’s other professors, however, believed that it would eventually work. By the time Bellemare arrived, they had formed a lab of 30 or so people within the Alberta Ingenuity Centre for Machine Learning (AICML), to try and crack the reinforcement learning code.

By the end of the 2000s, Edmonton was “one of the most prolific places on the face of the earth in terms of graduating AI students,” says Cameron Schuler, the organization’s executive director from 2010 to 2018. Those graduates didn’t have many places to go, though. Only a few professor or postdoctoral positions opened up at universities each year, and corporate Alberta “wasn’t overly interested in AI at the time,” he says.

Some from the Edmonton AI school went to Silicon Valley to work as regular software engineers. Others left tech altogether. “We were still in the AI winter,” says Brian Tanner, who studied at UAlberta between 2003 and 2010. He never finished his PhD, instead moving back to his hometown of Winnipeg to run a fire-safety company.

Other UAlberta graduates found work at DeepMind, which at the time was a little-known AI startup based in London. Canadians were at the heart of DeepMind’s early work, and UAlberta alumni formed its reinforcement learning core. Bellemare arrived in September 2013, joining the likes of David Silver, whose doctorate Sutton supervised, and Vlad Mnih, a UAlberta master’s student who’d gone on to a PhD at the University of Toronto under neural networks pioneer Geoffrey Hinton.

In those early days, the AI community was skeptical of DeepMind’s work, Tanner says. Many predicted the startup would be “a money pit” and “a total waste of time.” In 2012, when Silver called Tanner to ask if he’d be interested in a job at DeepMind in London, Tanner said no.

Then the AI winter began to thaw. In December 2012, Hinton and two of his students in Toronto presented proof that a neural network could significantly beat other AI systems at classifying images.

In London, DeepMind was also generating buzz—and UAlberta alumni were playing a key role. Mnih led a team that combined Alberta reinforcement learning and Toronto neural networks into a new kind of AI system that learned to play classic Atari 2600 games by “watching” the screen. It got a lot of attention. “When people see a game like Space Invaders or Pong or Breakout, they know it—they understand it,” says Bellemare, who played a key role on the project.

From left, Go player Lee Sedol, DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis and the firm’s reinforcement learning lead David Silver speak in Seoul during Sedol’s 2016 exhibition series with DeepMind’s AlphaGo AI system. Photo: Kim Min-Hee, Pool/Getty Images

DeepMind’s next AI trick also owed a lot to UAlberta. In March 2016, its AlphaGo system beat Lee Sedol, the best human in the world at the Chinese strategy game Go. Silver, DeepMind’s reinforcement learning head, had been working on Go-playing AIs since his time in Edmonton.

Back in Edmonton the next year, the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute (Amii)—a rebranded AICML—was chosen as one of three research hubs to deliver the federal government’s new $125 million Pan-Canadian AI Strategy. Amii was also trying to get industry more interested in AI, encouraging big businesses like RBC to open labs in Edmonton. By early 2017, the institute had “a queue of about 175 companies wanting to work with us,” Schuler says.

At the same time, Sutton had been talking to two other research leaders at UAlberta, Michael Bowling and Patrick Pilarski, about building closer ties to the private sector. “We are a world-class research place,” Sutton says they thought at the time. “Why don’t we do some world-class company building?”

DeepMind liked what it saw in Alberta. In July 2017, Hassabis announced the firm would open a research lab in Edmonton to pursue “core scientific research,” led by Sutton, Bowling and Pilarski.

The company’s arrival validated Edmonton’s underappreciated AI expertise, according to people in the industry, and was reward for Alberta’s longstanding investment in the technology. “It definitely gave some recognition to the area,” says Schuler, now chief commercialization officer at Toronto’s Vector Institute.

DeepMind also helped deepen Alberta’s AI talent pool by keeping top researchers in the province and bringing others back. In early 2017, Finbarr Timbers, an Edmonton-born and -raised data scientist, had been applying for jobs in Silicon Valley. Then DeepMind Alberta opened its doors. “This was the dream job, and I could get in without having to leave my home city,” says Timbers, who joined the lab in November 2017 as one of its first research engineers.

DeepMind’s arrival in Alberta also brought Tanner back. Some six years after turning down DeepMind in London to stay in Winnipeg, he sold his fire-safety business and moved back to Edmonton to join the firm’s new office as a research developer. It was, he recalls thinking, a “second shot at a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Former DeepMind Alberta colleagues Alex Kearney, left, and Brian Tanner co-founded Artificial Agency, a startup that makes AI tools for game developers. Photo: Larry Wong for The Logic

Inside DeepMind Alberta, the new hires worked in groups under Sutton to try and make fundamental advances in reinforcement learning, and under Bowling on systems to master more kinds of games. The office eventually grew from 10 to 27 people. While DeepMind’s London headquarters worked on bigger AI applications that required huge processing power, the Edmonton lab focused on earlier-stage AI research, Tanner says. “We were a very ideas-driven team.”

Former DeepMind staff say the firm had access to larger quantities of compute, and a more organized and experienced team than the academic labs in which they’d previously worked. “When industry is good, it kind of can’t be beat,” says Sutton, thanks to an alluring mix of more resources, good pay and fewer distractions. In addition to their research, star professors in a university computer science department still have to teach and apply for grants, and their academic labs are filled with students still honing their skills.

DeepMind, by contrast, could afford to bring together dozens of already-trained researchers to just do science, says Bellemare, now a co-founder and chief scientific officer at Montreal-based Reliant AI, which makes AI tools for pharmaceutical firms.

Abhishek Naik was among those drawn to Alberta by a mix of Sutton and DeepMind. Under Sutton’s supervision, his doctoral thesis focused on developing systems that continued learning through their lifetimes, like animals are hardwired to do. To test his algorithms, Naik worked with engineers at DeepMind including Tanner to create an open-source library of never-ending challenges. “I had some vision of what it could be,” he says—and DeepMind helped make it real.

DeepMind Alberta had quickly become a default dream for aspiring AI researchers in Edmonton. With DeepMind gone, they would need to make other plans.

In November 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT. It sent Google, and DeepMind, into turmoil.

Researchers at Google Brain had invented the technique behind the LLMs that powered ChatGPT five years earlier only to dawdle on rolling out generative AI products. Now Google had to play catch-up.

ChatGPT was “met with maybe more than healthy skepticism” inside DeepMind broadly and the Edmonton office specifically, Tanner says. Many researchers in Edmonton shared the view that generative systems were just regurgitating the material on which they had been trained. DeepMind Alberta hadn’t been working on LLMs, but Tanner drafted a proposal to explore how much they might benefit from reinforcement learning.

Quite a bit, it turns out. Today, leading AI labs use reinforcement learning to fine-tune their LLMs to produce better results, while the most advanced reasoning models use the technique to play out different solutions for tasks and problems, and pick the best one.

The Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute traces its history back to 2002, when the provincial government and University of Alberta jointly established a new AI centre. Photo: Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images

DeepMind Alberta’s closure in January 2023 meant Tanner’s project never got going. The firm told staff it was shutting the Edmonton lab because it wasn’t housed in an existing Google building like the unit’s other sites. Several former DeepMind Alberta employees said the firm handled the closure well, offering researchers and engineers positions at other DeepMind offices in Canada or the U.K. if they wanted to move.

While they considered those options, others in Edmonton’s tight-knit tech industry made clear they had alternatives. AI fund Flying Fish Ventures held office hours at Amii for a dozen or so former DeepMind staff who were considering working at or launching startups. It was a chance “to be helpful, but also maybe be part of their next step,” says principal Tiffany Linke-Boyko.

Seattle-based Flying Fish had hired Linke-Boyko, a former CEO of Startup Edmonton, in April 2022 to run a new Edmonton outpost because of the city’s AI talent and expertise in reinforcement learning. DeepMind’s presence had helped reinforce the VC firm’s belief in the city. “The ironic thing is that, as investors, we’re always like, ‘When are people leaving these places?’” says Linke-Boyko. Suddenly, many were seriously thinking about leaving DeepMind.

Kearney hosted gatherings at coffee shops in Edmonton where DeepMind staff discussed the opportunities they might pursue. Generative AI was clearly going to change the tech sector, and Kearney was increasingly drawn to the idea of working with a small, focused team to build a startup. “It just felt like the right time to take a risk and do something new,” she says. So she did.

Almost all the former staff of DeepMind Alberta are still in Edmonton today.

Kearney and Tanner, along with two other DeepMind Alberta colleagues, co-founded Artificial Agency in March 2023. The startup is developing AI models and tools that game developers can use to bring their work to life.

Artificial Agency’s game engine launched in July. The company claims it can make non-playable characters more realistic than ever and turn wooden in-game interactions into complex conversations.

The firm’s technology also lets developers add “game directors” that adapt the game in real-time based on players’ actions. The tool has full control over the world—“almost like a little God,” says CEO Tanner. Artificial Agency claims studios have already shown interest in using its technology in games under development.

Like so many of the field’s best minds, Kearney is focusing on games because they make the esoteric science of reinforcement learning more understandable to the public. “We all play,” says Kearney. “That’s tangible, anyone can get that.”

Kearney, who is Artificial Agency’s head of agents, also wants to inspire more startup founders in Edmonton. The firm now employs 25 people, on par with DeepMind Alberta at its peak. Artificial Agency has raised US$16 million in venture funding to date, from backers including Flying Fish, Toyota Ventures and Radical Ventures. Two of the startup’s original co-founders left earlier this year, with one joining DeepMind Montreal.

Adam White, left, Martha White and Alden Christianson, not pictured, co-founded RL Core Technologies, a startup selling industrial automation software for water treatment plants. Photo: Larry Wong for The Logic

Edmonton remains “an underdog,” compared to other tech clusters in Canada, according to Martha White, a UAlberta professor and CEO of RL Core Technologies. Despite that, or perhaps because of it, “it’s a very supportive ecosystem,” she says. DeepMind’s closure helped return some talent to the pool, and RL Core Technologies is among the beneficiaries—her co-founders, husband Adam White and Alden Christianson, are both DeepMind Alberta alumni. Founded in October 2023, the firm uses reinforcement learning to help automate industrial facilities like water treatment plants. It’s an extension of work the Whites had been doing at Amii before DeepMind quit Alberta.

The technology saves clients money by reducing the amount of power and chemicals they use, while helping their filters and equipment last longer. “We’re creating the software for industrial automation,” says White, RL Core’s CEO. The firm has raised US$5.79 million from backers including Flying Fish and TQ Ventures.

Edmonton’s AI startup scene is now in rude health. Linke-Boyko says the number of firms that pitch their ideas to Flying Fish has increased, and more students at the city’s universities are considering entrepreneurship as an alternative career path to academia or a job at a Big Tech firm. “There’s some really exciting momentum,” Linke-Boyko says.

Post-DeepMind, it’s also easier for Edmonton startups to access capital, according to Timbers, who advises RL Core backer TQ Ventures on AI investments. “We’re now on the circuit of places that VCs visit,” he says. Thanks in part to DeepMind, some of tech’s most high-profile executives and investors “have eaten at Tres Carnales and been to Oilers games.”

In addition to his VC work, Timbers is lead research engineer for Ai2, a Seattle-based AI research non-profit, where he’s applying reinforcement learning to LLMs. “I want to work on the stuff that is most useful or most promising,” he says; at the moment, that’s generative AI. Sony AI, meanwhile, has snapped several former DeepMind staff to form a small Alberta research hub. Those jobs have kept people in Edmonton, where they’re still collaborating today.

Alberta also continues to produce world-leading AI science. Sutton is currently working on step one of his 12-part Alberta Plan for AI Research, which he published with Bowling and Pilarski shortly before DeepMind left Edmonton. Designed to last up to a decade, the plan tries to address what Sutton sees as a major problem with current machine learning systems like LLMs: they don’t have goals, and they don’t learn. “An essential part of intelligence is that you keep learning,” he says.

The first step involves perfecting the basic units for a new kind of neural network that can generalize and learn continually. Sutton and DeepMind’s Silver also recently published a paper predicting that a new generation of AI agents will “acquire superhuman capabilities by learning predominantly from experience.” The article “has caught people’s imagination” and increased interest in the Alberta Plan, Sutton says.

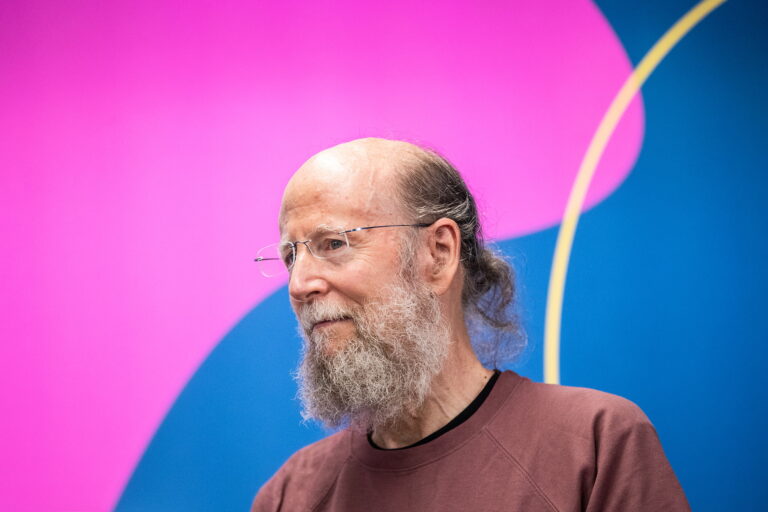

University of Alberta professor Richard Sutton, left, is working on AI systems that learn continually, while Amii CEO Cam Linke helps researchers apply the technology to fields like medicine and space. Photo: Larry Wong for The Logic

Sutton has always focused on the fundamental, unanswered questions of AI, and he says DeepMind never pressured him to come up with commercial applications for his work. But he couldn’t persuade the firm’s senior leaders to focus on systems capable of continuous learning. It was also difficult to do “scientific, systematic, careful, thoughtful research in AI” at DeepMind, Sutton says, because the firm was too busy chasing “the hype and the buzz” of the field. “I think better outside of that company,” says Sutton, who’s wearing a DeepMind hoodie.

Sutton is doing his work on the Alberta Plan at UAlberta, Amii and at Keen Technologies, a startup he joined in September 2023 that’s pursuing artificial general intelligence. He’s also helping raise money for the Openmind Research Institute, an Edmonton-based non-profit he co-founded in November 2023 to back young AI researchers to pursue their scientific interests without the pressures of academia or industry.

Amii and UAlberta have stepped up, too, hiring former DeepMind Alberta staff and creating 20 new faculty positions to focus on applying AI to areas like health and energy; Bowling played a key role.

Corporate Alberta, much like the rest of the world, is now very much interested in AI. As a result, Amii is getting its breakthroughs out into the world via a residency program that dispatches AI graduates to help smaller industrial firms adopt the technology. There’s now “a lot more opportunity” for AI talent in the province, says Amii CEO Cam Linke.

For the five and a half years between DeepMind Alberta’s arrival and departure, the lab took up a lot of space in the general conception of Edmonton’s AI scene, and in the ambitions of the city’s young researchers.

The firm’s exit broke the spell. Naik, for one, realized he’d been on autopilot, imagining his future at DeepMind. “Once the office closed, I had a lot of thinking to do,” he says. Long enthralled by the cosmos, he started volunteering with a group of UAlberta students building cube satellites.

Today, Naik works at the National Research Council, where he hopes to develop space rovers and robots that will one day control themselves using reinforcement learning as they explore distant planets. “AI is my expertise, space is my passion,” says Naik, whose home is filled with Lego models of the Space Shuttle Discovery, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Apollo Saturn V rocket.

DeepMind proved it was possible to build a world-class lab in Edmonton, fill it with top researchers, and do great work. The talent it left behind is now pushing that work ever further. For his part, Sutton believes Edmonton’s AI ecosystem has come of age. “There’s nothing holding us back,” he says, “except our imagination and our will.”

With files from Jesse Snyder