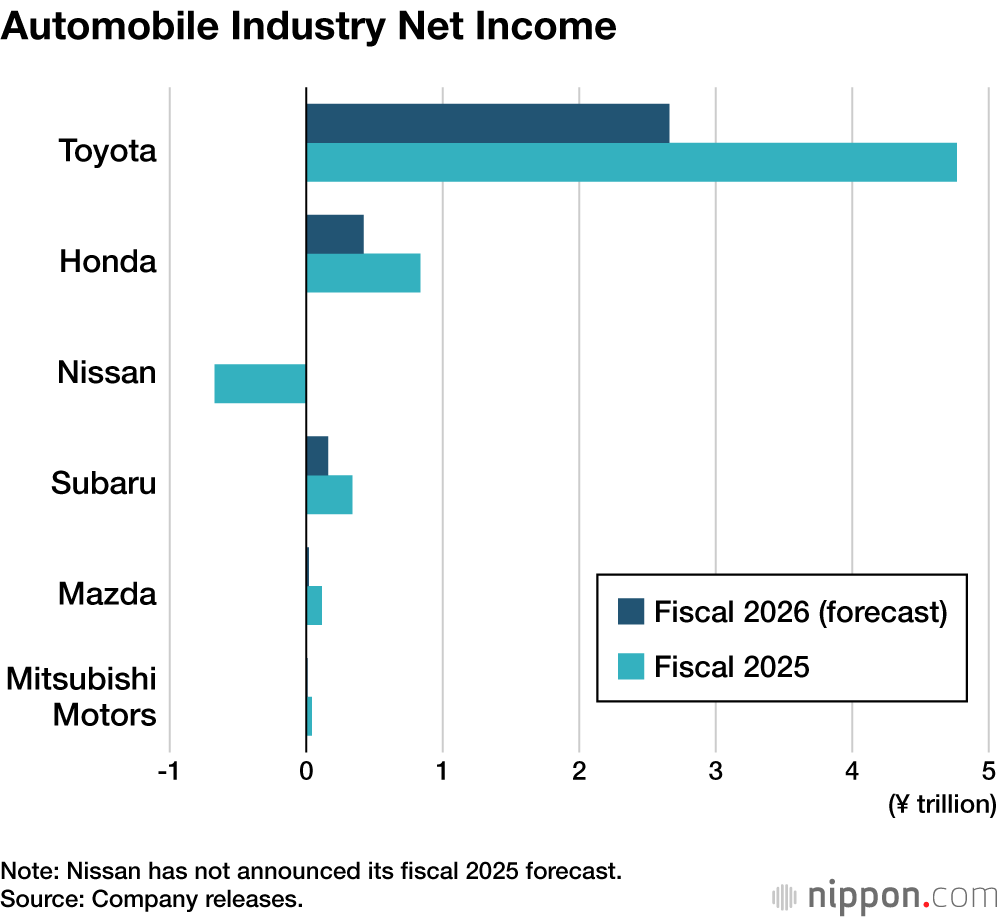

Japan’s automotive industry is suffering a severe blow from US President Donald Trump’s punitive tariff rates. The top six automakers are looking at a ¥2.6 trillion blow to their bottom line, meaning pain for the Japanese economy as a whole and possible industry consolidation going forward.

A ¥2.6 Trillion Impact

“It’s likely that America’s high tariffs will remain even after the Trump administration,” said an executive of a leading automaker with a pained expression. “We can’t offset the costs just by raising prices.” It was August, and automakers had recently announced their earnings for the April–June period of 2025.

The 25% additional tariffs the US administration of President Donald Trump introduced in April on cars and their parts hit harder than automakers had anticipated. For the April–June period, Nissan, which is struggling with weak sales, and Mazda, which relies heavily on exports to the United States, both recorded net losses. Most of Mitsubishi Motors’ revenue was wiped out, and Honda’s was cut in half. Toyota and Subaru saw their earnings drop by more than 30%.

Automakers dealt with tariff costs in the April–June period by lowering export prices from Japan and having their US-based operations responsible for sales absorb part of the burden. They also shouldered part of the costs of parts manufacturers. The impact was severe for companies like Mazda and Subaru, for which US sales make up a significant portion of their business and which are highly dependent on exports from Japan. Across the industry, according to estimates for April–June released by the automakers as of early August, the effect is projected to total ¥2.6 trillion, taken out of operating profit—and this total was based on assumptions that tariffs would be reduced to 15% from August 1 based on the July bilateral agreement, so the actual impact may be even greater.

Expected Impact of US Tariffs in Fiscal 2025

Toyota: ¥1,400 billion

Honda: ¥450 billion

Nissan: Up to ¥300 billion

Subaru: ¥210 billion

Mazda: ¥233.3 billion

Mitsubishi Motors: ¥32 billion

Prepared by the author for fiscal 2025 (April 2025–March 2026) based on materials released by the companies (calculation methods differ by company).

In September, President Trump finally signed an executive order that would reduce tariffs on Japanese cars and auto parts to 15% in exchange for major investment from Japan into the United States. Even so, the rate remains high, and the burden on Japanese automakers is heavy.

Shifting Away from Free Trade

Japanese automakers had fully leveraged America’s liberal trade system, arguably benefiting more than any other industry. Tariffs on Japan-produced cars were low, at just 2.5%. The companies built sales, production, and supply networks for parts and raw materials within the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) framework from Trump’s first term. They took advantage of reduced or waived tariffs for completed vehicles, as well as for parts that met specific criteria.

Furthermore, since the 1990s, Japanese automakers have been growing increasingly dependent on the US market as the Japanese market shrank due to demographic decline and younger generations grew less interested in cars.

The situation changed dramatically with the start of Trump’s second administration in January 2025. Automobiles and parts were hit with an additional 25% of tariffs in April, and raw materials such as steel and aluminum were also subjected to high tariffs. According to the UK research firm Oxford Economics, the average tariff rate in the United States as of August stood at 16.7%, up sharply from the single-digit level of last year.

Trump Won’t Let Go of Tariffs

In Japan, calls continue for tariff reductions or relief measures, but in the United States, there are reasons why tariffs cannot be easily removed. One of the funding sources for the Trump administration’s large tax cuts, one of its key policies, is revenue from tariffs. In July, Trump signed into law a bill permanently extending individual income tax cuts from his first term, which were set to expire at the end of 2025, along with tax exemptions on tips and overtime pay for certain workers, such as those in restaurants.

Initially, the US Congressional Budget Office projected that permanent tax cuts and other measures would increase the federal deficit by $3.4 trillion over 10 years through 2035. But in August, citing higher tariff revenues, it revised its forecast to show a $4 trillion reduction in the deficit and improved fiscal health. During last year’s election campaign, Trump promoted high tariffs as a “cure-all” that would simultaneously deliver tax cuts, deficit reduction, and a revival of manufacturing and jobs. Reacting to the CBO forecast, he expressed satisfaction and a sense of vindication.

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, a key figure both in fiscal and tariff policy, also appears to be keen on securing tariff revenues. In late August, he said that America’s annual revenue from tariffs will exceed $500 billion and could even reach $1 trillion. While the Japanese government considers Bessent a moderate on tariffs and pro-Japanese (according to a government insider), what Bessent is most concerned about is the US Treasury market (according to a researcher at an American think tank). He is expected to remain cautious about tariff cuts that could raise the deficit.

Since Trump’s first victory in 2016, the industrial area called the Rust Belt which includes parts of Michigan where the auto industry is concentrated has become a decisive battleground in elections. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat seen as a future presidential hopeful, criticized Trump’s disorderly tariff policy in April but said she agreed there was a need to promote fair trade, signaling some measure of alignment with Trump’s stated goal of bringing jobs and supply chains back home.

A senior Japanese government official also emphasized that even if the administration changes, once tariffs have been raised, it is difficult to lower them again. According to this official, the series of high-tariff measures turning away from free trade may not be just a temporary policy under Trump but may very well be a structural policy shift in the United States going forward.

Industry Alliances

The United States is the largest customer for Japan’s leading automakers, and some believe changes there could spur new alliances and partnerships in the industry. According to sources, Nissan is in talks with Honda to produce pickup trucks at its US plants, which are struggling with low capacity utilization, and supply them to Honda. Delivery of other types of vehicle is also under consideration. Although merger talks between the two companies collapsed in February, they are moving to rebuild relations.

Mitsubishi Motors, which agreed to procure electric vehicles from Nissan for the North American market, is reconsidering the details of the arrangement in the light of US regulatory changes. Within the industry, speculation persists that Toyota will expand collaboration with Mazda and Subaru, in which it holds stakes. “Only Toyota has the strength to weather the Trump tariff crisis on its own,” said one megabank executive. “The others will be forced into alliances or restructuring.”

Automakers are scrambling to adjust to what Fujimura Eiji, a director at Honda, has described as the “new normal,” where it is assumed that US tariffs are here to stay. They plan to reduce tariff burdens by slashing costs and revising product lineups based on profitability in fiscal 2025.

Companies are also eyeing opportunities to pass on costs to consumers in the US market. The problem is timing. There are concerns that raising prices would hurt sales. One executive explained that no company really wants to be the first to make large price increases. They are watching the moves of European and Korean rivals as they decide when to act. The executive added that the decision is particularly difficult because if the currently strong US economy slows down, consumer spending will drop, making price increases impossible even if desired.

Many believe that, in the medium to long term, automakers will have no choice but to increase production in the United States. According to the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association, the auto industry, including suppliers of parts and raw materials, employs about 5.5 million people domestically, accounting for roughly 10% of all industrial employment in Japan. Capital investment and R&D total ¥5.5 trillion, or about 30% of all manufacturing. If production shifts overseas, the effects would be felt across the entire Japanese economy. “We need a nationwide approach,” says an executive at a leading automaker.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)