Bookends with Mattea Roach32:33What would it take to become the first Cherokee astronaut?

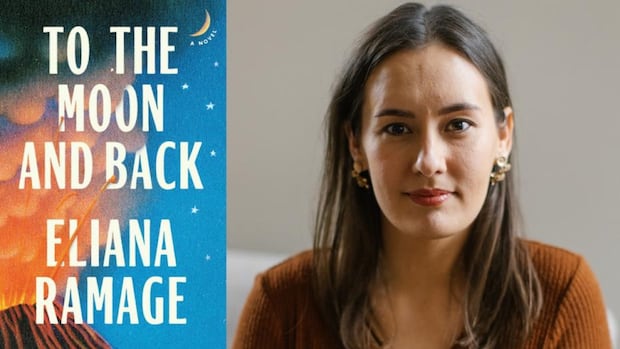

Eliana Ramage’s debut novel To The Moon and Back tells the story of Steph Harper, who is dead set on becoming the first ever Cherokee astronaut.

The book follows Steph through growing up in the 90s in Oklahoma, the messiness of university life and adulthood, embracing her queerness and setting off on the journey of a lifetime to realize her dreams.

It also explores the lives of her sister, mother and the other women that she’s in community with, who all have their own stories about belonging, identity and family.

“I was writing about these very different Cherokee women who all had those same questions, but they were all given the space to take that in different directions,” said Ramage, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, on Bookends with Mattea Roach. “There are different ways of showing up as a Cherokee person.”

Ramage joined Roach to share how she experienced coming-of-age in tandem with her characters and the bright future she sees for young Cherokee people.

Mattea Roach: Where does your interest in space and in this astronaut journey come from?

Eliana Ramage: I’ll preface this by saying I’m a writer, not a scientist. There are people who do both. That’s not me. I am really interested in the story of science though, what it means to us as humanity as sort of a group project and how it represents possibility.

In this particular story, the first time we meet Steph, she’s escaping this traumatic incident. Space, at that point, for her, represents escape, taking this story and starting over with a new one, forgetting everything that came before all of that history.

I wanted to write against that because I feel like as a Cherokee person, the dominant story that’s told about us is the Trail of Tears. It’s a story of loss, as if there were kind of like a point of authenticity in the past, and then everything that goes from that moment of removal from the homelands is like becoming less and less and less.

Of course, that’s not true. Cherokee people have always changed. Everyone has always changed. What’s exciting about space to me is how, when I think about the future, it calls on us to keep looking, to let that story keep going. So this is a book where I wanted to use space to be able to contemplate Cherokee identity today and what Cherokee identity could look like 1000 years from now.

How did Steph come to be as a character?

That’s such a good question. She is really frustrating. She is so single-minded in a way that I, in some ways, admire. I think it’s interesting and it’s complicated and exciting to spend time with people who define themselves by their ambition. That’s not how I understand myself. That’s not my most important value.

(Simon & Schuster)

(Simon & Schuster)

And so as much as Steph sometimes makes me uncomfortable, over the years as she’s coming of age, I was also coming of age. I wanted to kind of explore this area that is interesting to me but is not home to me.

What was it like to come of age with your character as you were writing her and as you were learning about her and perhaps learning about yourself?

I can’t really think about this book without thinking about her coming-of-age and my coming-of-age. It worked out really well that it took so long, even though I wanted it to go faster.

The way that I think about this in terms of the parts of my life that I spent writing it were that I started it when I had just left my parents’ home for college and I turned in the edits the night that my daughter was born, and a lot of change happened in that time. That part of my life did not go exactly the way I thought it would. Then this book didn’t turn out to be like a simpler, more straightforward story that I originally thought it would be.

I can’t really think about this book without thinking about her coming-of-age and my coming-of-age.- Eliana Ramage

I think that it really changed the way I understand coming of age in books and in real life because as I was writing it, I thought, “Oh, this book is going to take us ’till age, 26 for Steph because that’s when you’re fully realized as a person.” And then I was like, “Okay, not quite. Maybe, 28, 30.”

Now I’m 34 and I’ve arrived in this place of understanding that there is not this point of arrival. I have this understanding and appreciation that just like the Cherokee story is going to continue, our own individual stories are going to continue, the change that these characters go through, the mistakes that they make, the starting over over and over again. Now, that’s something that I think is really beautiful about life.

What are your hopes for the future, for your kids, as they grow up? What do you hope their engagement will be with Cherokee culture, with Cherokee identity?

I hope that they can understand themselves as linked to both the past and the future and as part of this continuing Cherokee story.

Being part of that story could mean connection to other Cherokee people, it could mean the smallest of details, like if my daughter knows just like the tiniest bit of the language, like I know the tiniest bit, then that would be really powerful to just have access to that, or to these stories, or to just like be part of something that has survived for a long time.

But I don’t want that story of survival to be one of, “You went through A, B and C loss, loss, loss and still you are here.” I would like her to have some excitement about the future. I think that if she were to think about Cherokees on Mars, I would hope that that didn’t feel like the farthest place you can get from Cherokee identity. I would hope for Cherokees on Mars to just feel like the next part of the story.

Eliana Ramage and her daughter on a recent visit to Nova Scotia. (Submitted by Eliana Ramage)

Eliana Ramage and her daughter on a recent visit to Nova Scotia. (Submitted by Eliana Ramage)

This interview was edited for length and clarity. It was produced by Ailey Yamamoto.