Dying to Know

Mystery Writers Answer Burning Questions

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

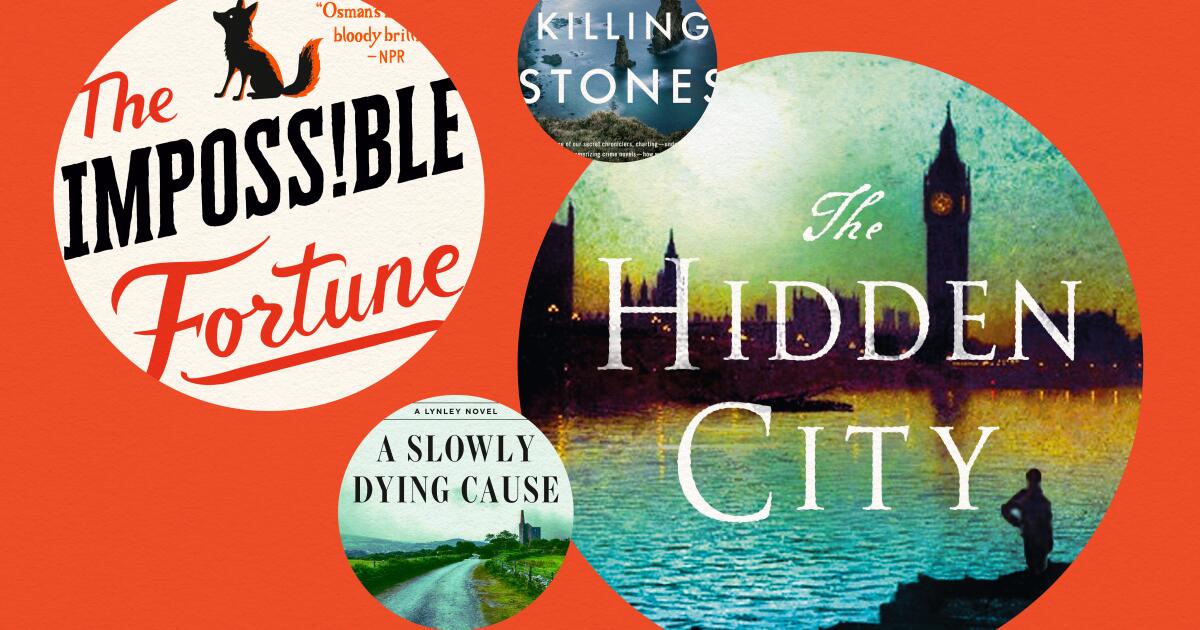

This fall, check out these noteworthy British mysteries, three with film or television connections and a fourth that’s ripe for adaptation. Their authors, from both sides of the pond, weigh in on two central questions — what does it take to write a “British” crime novel and what writers would they invite for a proper British tea?

A Slowly Dying Cause

By Elizabeth George

Viking: 656 page, $32

Out now

On the heels of the rebooted “Lynley” TV series comes George’s 22nd mystery set in Cornwall and featuring the unlikely pairing of the aristocratic Detective Inspector Thomas Lynley and the all-too-human Detective Sergeant Barbara Havers. Michael Lobb, 56, a Cornish tinsmith and jeweler, is found stabbed to death in his studio. Numerous flashbacks include Lobb’s diary entries, which lay bare his marital infidelity and family abandonment for a second marriage to a woman not much older than his children. In addition to Wife No. 2 and a would-be business associate, suspects include the dead man’s abandoned first wife and adult children as well as the workers on the Lobb property who just happen to be related to Daidre Trahair, the London veterinarian who’d previously deflected Lynley’s romantic overtures.

It takes 120 pages for Lynley himself to show up, called home on family business with Havers in tow, she on one week’s enforced bereavement leave due to the death of her mother. It’s a convenient setup for Lynley being called to join the investigation by the Cornish inspector on the scene and George to write with authority about a part of England she clearly loves and knows well. While readers’ attention might flag over the investigation, or the novel’s numerous subplots and legal machinations, George is setting a complicated trap of misdirection and a diabolical level of hiding in plain sight while exploring love and relationships from multiple vantage points. An emotional revelation promises the possibility that Lynley’s cause may not be dying after all.

What makes a British mystery distinctive? Which begs the question: Can someone who is not from Britain write a British mystery?

Of course, the number one thing that makes a British mystery distinctive is that it’s set in Great Britain, where police do not carry guns and where over the years homicide investigations have undergone some remarkable changes. To make that understandable and realistic for the reader, I’ve interviewed many British police professionals, from detectives to press officers to constables on the street. That enables me to give the flavor of an actual police investigation without using the myriad individuals who are actually part of a homicide investigation. There is additional information that I’ve had to amass on the criminal justice system, and to do this I’ve interviewed barristers, solicitors, magistrates and judges. So it’s definitely possible for someone who isn’t British to write a British crime novel, but one has to be willing to put in the work to do it.

How is the recently rebooted “Lynley” series different from the original?

All of the adaptations for this new series are of books that haven’t been adapted before now. Also, this series is different from the original in that entirely new actors are playing the characters, and my detectives are part of a murder squad that is centered in Norwich and not in London. This is, of course, an enormous change. But I’ve seen the episodes of the season in rough cut and while they differ from the novels, they’re really great fun to watch and I enjoyed them thoroughly. People will be very surprised by the casting — especially of Barbara Havers — but I think both of the actors will grow on the viewer. There are moments that stand out particularly as “pure Lynley” and “pure Havers.”

You’re inviting three British crime novelists, living or dead, to tea. Who would they be and why?

Oh, gosh. That’s a tough one. I would definitely invite Dorothy L. Sayers as her life after Lord Peter Wimsey really interests me and I’d love to know how she adjusted to it, having made Peter Wimsey so famous. I would invite Patricia Highsmith so that we could talk about “Ripley” and how she feels about the latest adaptation of Ripley in comparison to the film with Matt Damon. I would stretch the idea of “British crime writer” to Ireland and invite Tana French to pick her brains about her gift at depicting locations so brilliantly.

The Impossible Fortune

By Richard Osman

Pamela Dorman Books: 368 Pages, $30

Sept. 30

In “The Thursday Murder Club’s” fifth outing, the Coopers Chase retirement community’s amateur sleuths are in a lull after their last case. Elizabeth, a former spy, is grieving her husband; psychiatrist Ibrahim is counseling an ex-con; while Joyce is busy with her daughter’s wedding. At the reception, when cybersecurity expert and best man Nick Silver confides to Elizabeth about an attempt on his life, she feels called back into action and life: “For the last year her heartbeat has felt like a machine, a mechanical pump keeping her alive against her will, but now it feels flesh.” Silver’s subsequent disappearance and the bombing death of his business partner, Holly Lewis, reveals the pair was in the throes of selling a small fortune in bitcoin. That surfaces suspects aplenty and serves as a counterpoint to the TMC members’ various other crime-related concerns. “The impossible Fortune” strains at times to manage its numerous plot threads and twists; that’s one of the quirkier hallmarks of Osman’s writing. But does that detract from the novel’s overarching message about the value of love, in all its forms, in the lives of these always-endearing characters? That would be impossible.

What makes a British crime novel distinctive? Which invites the question: Can someone who is not British write one?

British people are far too polite to ever tell the truth about anything, which makes us all potential murderers. The moment a British person says to a neighbour, “Well, your garden is looking lovely today, Geoffrey,” you know for certain that Geoffrey is about to be murdered with a pickaxe.

“The Thursday Murder Club” has been brought to the screen for the first time. How involved were you in the book-to-screen adaptation?

I chose not to get involved in the film and leave it to the professionals. My job is to give everything in my head and heart into writing the books. The film is like a lovely bonus. Like a grandchild instead of a child, I get all of the fun with none of the responsibility.

You’re inviting three British crime novelists, living or dead, to tea. Who would they be and why?

Great question. Dorothy L. Sayers — I think of her as “the hipster Agatha Christie” — Ian Rankin and, if I’m allowed to include him as a crime writer (surely George Smiley is one of the great detectives?), John Le Carré.

The Killing Stones

By Ann Cleeves

Minotaur: 384 pages, $29

Sept. 30

Ann Cleeves reportedly ended the Shetland mysteries with 2018’s “Wild Fire,” although Detective Inspector Jimmy Perez’s colleagues, led by DI Ruth Calder, continue in the TV series. (A 10th season is forthcoming on BritBox.) But readers were left wondering was this the end of Perez and his pregnant lover and superior officer, Willow Reeves, who by the end of “Wild Fire” had moved to Orkney — some 150 miles southwest of Shetland? So was Cleeves, who has now given Perez and Reeves a reprieve and readers a case that reintroduces the couple. Archie Stout, Perez’s oldest friend, is missing from his home on isolated Westray. Jimmy travels by boat from their home on the Orkney mainland to investigate and discovers his friend’s body close to an archaeological dig, a nearby stone artifact with spiral carvings the presumed weapon. As the case unfolds, so does the reader’s understanding of how Jimmy and his growing family have become intrinsically bonded to the Orcadian people and land, rich with history and customs. Skillfully and compassionately told, “The Killing Stones” may have been conceived as a standalone, but there are enough revelations about Orcadian culture and these emotionally engaging detectives for readers to hope for another Perez and Reeves mystery, and soon.

Why come back to Jimmy Perez after a long hiatus?

I thought I’d seen the last of Jimmy, but I felt a longing to go north again, a sort of homesickness. It occurred to me that it would be fun to explore Jimmy in a different set of islands, with his partner, Willow, as his boss. And it was interesting coming back to a character I believed I’d left behind and looking at him from a new perspective, putting him within different communities within Orkney, developing a new community to which he could belong. I’m definitely tempted now to continue writing about Jimmy and Willow. He might even develop a sense of humour!

For you, what makes a British crime novel distinctive? Which invites the question: Can someone who is not British write one?

As a Brit from the south of England, I have the same dilemma when I’m writing about Orkney. It’s the small details that make a book credible and authentic. I need to spend time walking in locals’ footsteps and listening to their preoccupations. I couldn’t write a book set in a place I’d never visited.

You’re inviting three British crime novelists, living or dead, to tea. Who would they be and why?

Vaseem Khan, Mick Herron and Val McDermid. They’re all alive, all good writers and great fun. They’ve moved British crime-writing away from its traditional subject matter. Though I suspect that Val and Mick might prefer beer to tea.

(Timothy Greenfield-Sanders)

The Hidden City

By Charles Finch

Minotaur: 288 pages, $29

Nov. 4

Over more than a dozen mysteries featuring the pioneering detective Charles Lenox, L.A.-based writer, book critic and COVID-19 diarist Charles Finch has blended his comprehensive knowledge of Victorian history with memorable mysteries equal to the best in the genre. In Lenox’s 15th outing, the detective, painfully aware he’s now 50, must rouse himself from lingering fatigue and physical pain from a stab wound sustained while in America. He’s meeting a Portsmouth ship arriving from India bearing his second cousin, Angela and — a surprise to Lenox — her lifelong friend and companion, an Indian girl named Sari. Lenox’s loyalty and affection for his first cousin, Jasper — who moved to India as a young man and lived there until his death — spurs him to welcome the two young women into his household in London. There he involves his wife, Lady Jane, who must balance securing their entry into London high society — and thus their future prospects — with her growing involvement in women’s suffrage.

Meanwhile, Lenox investigates the mysterious death of a chemist and the former occupant of rooms now inhabited by a beloved housekeeper from Lenox’s early days as a London detective working with Graham, his lifelong friend and former valet. The housekeeper, having spied a man sleeping in the vestibule of her building, believes he’s connected to the murder and thus fears for her safety. As Lenox and Graham, now an influential member of parliament, join forces to investigate the case, it leads them to a sordid, underground London, populated by the upper crust and criminal classes, the ordinary people caught in between who did not have what Lenox recognizes as his privilege or his opportunities. Finch does an excellent job of balancing these and other political and social elements while advancing the story of a detective yearning to reconnect at midlife to his sense of wonder and purpose. An intriguing denouement confirms that readers of icons from Charles Dickens to Anne Perry can do no better than spending time with Charles Lenox, his family and ever-widening circle of friends.

Charles Lenox was stabbed near the end of “An Extravagant Death.” What informed your sensitive descriptions of his recovery in “The Hidden City”?

I had a long illness during the time I was writing this book. As I recovered, regaining trust in my body was hard — progress felt so tentative, and the fear of regression was so stark. I was really interested in describing the emotion of that physical pain through Lenox. Maybe partly to understand it for myself.

For you, what makes a British mystery distinctive? Which begs the question: Can someone who is not from Britain write one?

Every British mystery lives and dies on feel — feel for the culture, its jokes, its food, its people. I’m American, and it’s hard to judge your own books anyway, so I don’t know if I pass that test myself! I do know that I’ve long lived inside the books of Trollope, Dickens, Austen, Gaskell. They’re my teachers. I hope that helps it feel real.

You’re inviting three British crime novelists, living or dead, to tea. Who would they be and why?

I adore this question! Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. He gave birth to us all. Agatha Christie. The best to ever do it. And Elizabeth George. My favorite living writer of British crime novels. The tea is lapsang souchong. The biscuits are custard creams. The conversation lasts way past dinner time.