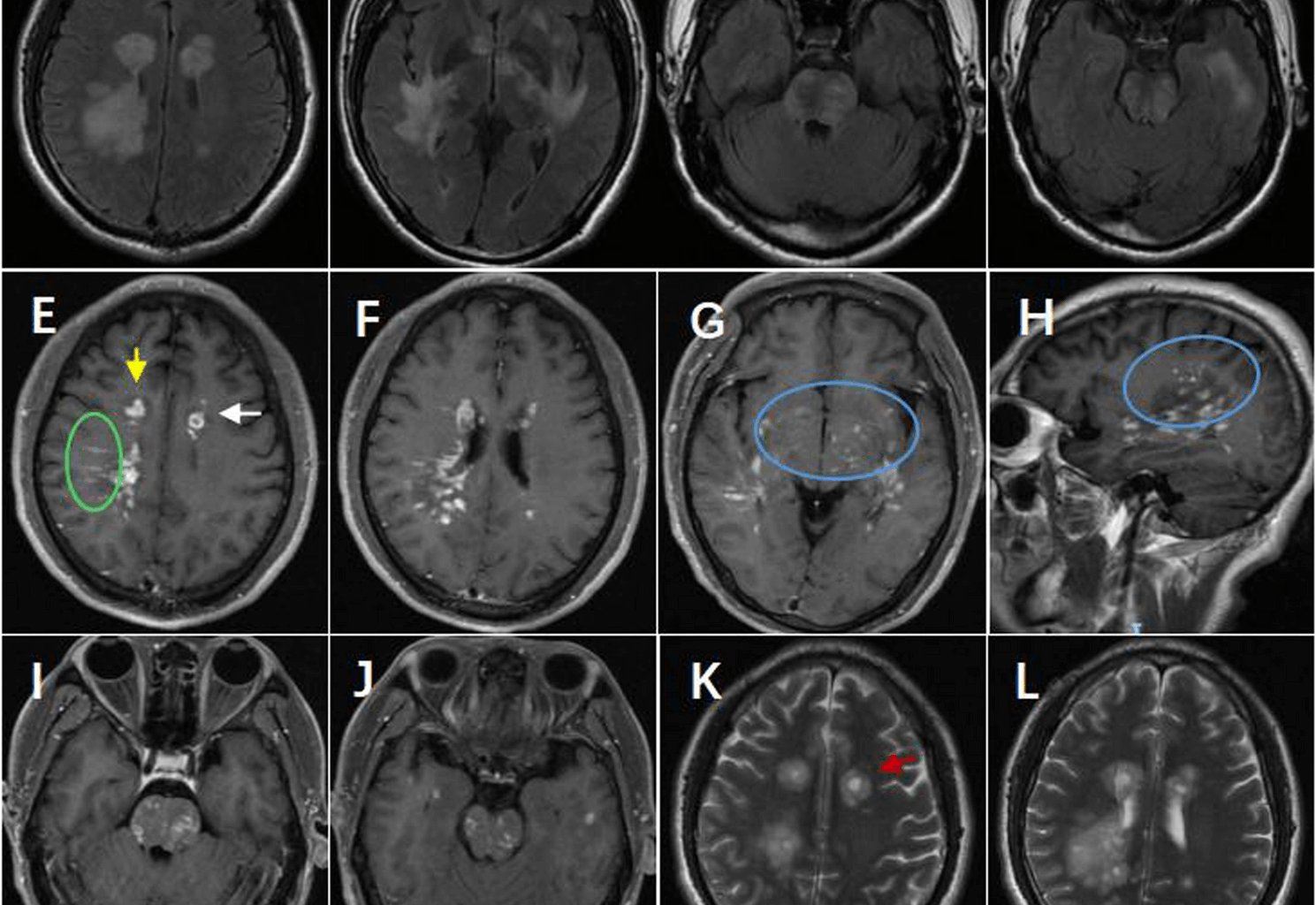

MOGAD is an immune-mediated inflammatory demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) [5]. MOGAD is considered distinct from both MS and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD). In this report, the patient presented with a clinical phenotype that included encephalopathy and brainstem syndrome. The patient also had multifocal T2/FLAIR hyperintensities in the supratentorial white matter, basal ganglia, and brainstem, which are pivotal features of MOGAD [6]. This study reports a case of MOGAD with rare “peppered” and perivascular enhancement on brain MRI (Fig. 1E–J). The “peppered” enhancement was more pronounced in the supratentorial region (Fig. 1G–H) and showed overlap with the fried egg sign on T2 images (Fig. 1K–L).

In addition to the aforementioned imaging characteristics, although no clinical deterioration or relapse was observed during follow-up, the patient’s cranial MRI revealed persistent progression of brain lesions. Unlike MS, neurological deterioration in MOGAD does not typically progress in the absence of relapses [7]. This case observed radiological progression during clinical stability in a MOGAD patient, a phenomenon that shares similarities with multiple sclerosis (MS), but requires verification through larger cohort studies.At the last follow-up, we suspected MS; however, a review of the entire disease course revealed that the initial clinical episode, strong response to high-dose corticosteroids, MRI features, and remarkable temporary improvement on MRI were consistent with the typical MOGAD [6]. Additionally, there were no other clinical episodes indicating MS. Meanwhile, multifocal deficits were accompanied by T2/FLAIR-hyperintensity lesions in the supratentorial white matter, juxtacortical region, deep gray nuclei, and brainstem (Fig. 2L–N). Therefore, despite red flag signs such as MS-like lesions and positive OCBs, we diagnosed MOGAD.

Challenges in diagnosing MOGAD persist despite established diagnostic criteria. The clinical features of MOGAD overlap with those of other CNS demyelinating diseases, including MS. Diagnostic confusion can also arise from radiological features, which may be attributed to other conditions and are not specific to MOGAD. Therefore, it is essential to analyze all findings comprehensively rather than focusing on any single aspect.

We investigated the mechanisms behind this pattern of disease progression and how to differentiate it from MS. The patient’s attention was drawn to positive OCBs, noting that OBC positivity is reported in approximately 10% of MOGAD cases [8]. OCBs can make differentiation between MOGAD and MS challenging. The significance of positive OCBs in patients with MOGAD has not yet been fully clarified. The new MOGAD diagnostic criteria have emphasized the need to rule out MS in the diagnosis [3]. However, there is still insufficient data to assert that all cases meeting red flags are MOGAD rather than MS. In this study, we speculated that patients with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD) who are positive for oligoclonal bands (OCB) may have an increased risk of disease relapse.OCB-positive MOGAD can mimic clinical and imaging features of MS. Therefore, patients with MOGAD and positive OCBs should be informed about the possibility of progression independent of relapse activity and closely monitored with CNS imaging during follow-up.

A previous observational study has revealed that corticosteroids are tapered gradually to mitigate relapse risk [9]. Maintenance therapy for patients with MOGAD remains disputed, particularly considering that approximately half of these patients present with a monophasic course [5] .Currently, predicting relapse in newly diagnosed patients remains challenging. A previous study has shown that bridging immunosuppressive agents with oral steroids is associated with better therapeutic outcomes [10] .Additionally, a prospective observational cohort study provided evidence that MMF therapy reduces relapse in patients with MOGAD [11]. Consequently, MMF was used for maintenance treatment in our patient. Unfortunately, a follow-up MRI demonstrated radiological progression.While large patches of irregular lesions, perivascular enhancement, and pepper-like enhancement were initially observed, they were not present at follow-up. The association between OCB positivity in MOGAD and MS-like phenotypes or progressive disease courses still requires confirmation through prospective cohort studies.For instance, perivascular and pepper-like enhancements indicate good responses to hormone therapy and effective prevention therapy with MMF.Current treatment decisions should be based on comprehensive clinical and radiological assessments rather than relying solely on a single biomarker. The cases reported in this study are merely descriptive clinical observations intended for academic discussion and do not constitute specific treatment recommendations. Regarding therapeutic strategies for MOGAD patients with OCB positivity, the clinical significance and optimal treatment approaches still require further validation through large-scale clinical studies in the future.

In summary, our case reveals an unusual characteristic of MOGAD in the brain MRI and emphasizes the features of neuroimage deterioration in the absence of relapses. Our findings also demonstrate that assessing imaging features and OCBs may help guide treatment decisions. Given the potential for subclinical disease activity in MOGAD patients (as evidenced in this study by persistent MRI abnormalities despite the absence of relapse symptoms), we recommend regular CNS MRI follow-up monitoring for all MOGAD patients (at least annually), with particular importance for OCB-positive cases.

MOGAD exhibits significant clinical heterogeneity in its disease course. Approximately 50% of patients demonstrate a monophasic disease pattern, and this subset may not require long-term immunosuppressive therapy. However, recent studies suggest that patients with MOG antibodies who are positive for cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands (OCB) face a higher risk of relapse [1,2,3].

Highlighting any challenges in diagnosing and managing MOGAD and suggesting areas for further research or improvements in clinical practice are important.