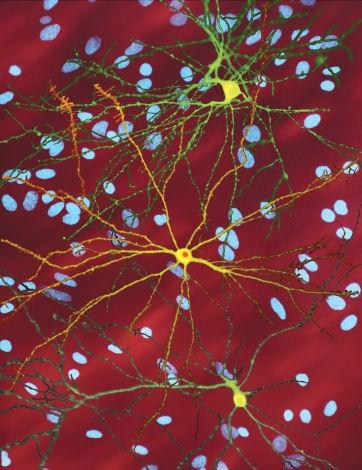

This image shows three brain cells with the faulty protein that causes Huntington’s disease. The bright yellow cell in the middle has built up a clump of this protein inside it. The blue spots in the background are the cell nuclei of nearby, unaffected brain cells.

Dr. Steven Finkbeiner, Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease, The Taube-Koret Center for Huntington’s Disease Research, and the University of California, San Francisco

New data from a gene therapy trial provide the first credible evidence that the progression of Huntington’s disease may be slowed by a single, targeted intervention. Huntington’s is a rare but devastating genetic illness caused by a single inherited mutation. If you carry the defective gene, you will almost certainly develop the disease, often in mid-adulthood. It affects about 30,000 people in the United States and places another 200,000 at risk.

For families facing Huntington’s disease, the search for meaningful treatment has been long and heartbreaking. The disease gradually robs people of movement, memory, and emotional stability, and until now, there has been no way to slow or stop it—only medications to ease symptoms. Many families live with the heavy knowledge that they or their children may face it one day as well. After decades of disappointment, a wave of cautious hope is now emerging. A new type of gene therapy—called AMT-130—is showing the first credible signs that it may actually slow the progression of Huntington’s disease. Unlike standard medicines that only treat symptoms, this experimental therapy targets the root of the disease: the faulty gene itself.

Huntington’s disease occurs because the huntingtin gene doesn’t function properly. The defect causes brain cells to produce a damaged protein that slowly poisons the nervous system over many years. What makes this disease especially cruel is its certainty: if you have the harmful version of the gene, you will develop symptoms. Genetic tests can reveal risk decades before the disease develops, leaving families burdened by years of uncertainty and worry.

What the New Therapy Does

The new therapy works by “turning down” the faulty gene inside brain cells. In the trial, doctors used a harmless, engineered virus to carry tiny bits of genetic instructions, called microRNAs, directly into specific regions of the brain. These microRNAs are designed to reduce the expression of the huntingtin gene, which produces the mutant protein responsible for neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. This means that it essentially tells cells to make less of the harmful protein. It’s a one-time treatment, delivered by surgery, rather than something patients would need to take daily.

Early results are striking: people who received higher doses showed approximately a 75% slowing of disease progression over three years, compared to similar patients who did not receive the treatment. These early findings suggest that gene therapy may have the potential to alter the course of the disease. For conditions like Huntington’s, which typically progress rapidly, this could mean years of preserved independence and quality of life.

Safety remains a central consideration for gene therapies, especially those involving direct delivery to the brain. In this study, side effects were manageable and aligned with expectations for neurosurgical procedures. Biomarkers—measurable substances that indicate the state of disease—in the brain showed favorable trends among treated participants. Importantly, no new long-term safety concerns were identified during follow-up. This is a critical milestone for therapies that induce lasting genetic changes. While these results are preliminary and warrant cautious interpretation, they point to a possible clinically meaningful benefit in a disease that has, to date, lacked disease-modifying treatments.

Why These Results Could Change the Future for Patients and Families

For decades, Huntington’s families have been told there is no way to change the course of the disease. Medications exist to reduce mood changes or uncontrolled movements, but nothing has been able to touch the relentless decline itself. The idea that a single treatment might slow Huntington’s at its source—for the first time—marks a turning point.

Multiple companies have pursued diverse strategies for Huntington’s disease, though many have faced setbacks. Roche and Ionis Pharmaceuticals discontinued their tominersen program, and early candidates from Wave Life Sciences did not achieve sufficient reduction in mutant huntingtin protein. Nevertheless, research efforts continue, including Wave’s WVE-003, immune-modulating agents from Selecta Biosciences, and small molecule therapies from PTC Therapeutics. Academic groups are also advancing preclinical gene-editing research.

Given these prior challenges, the safety and efficacy observed with uniQure’s approach are particularly noteworthy. The use of a viral vector may help overcome obstacles in delivering and sustaining therapeutic effects that have limited the efficacy of earlier interventions. Still, the research on AMT-130 is in its early stages, involving a few dozen patients in the U.S. and Europe. Larger studies are needed to validate the results. If validated, the impact could parallel advances achieved with gene therapies for conditions such as hemophilia or spinal muscular atrophy.

From a commercial perspective, a therapy that modifies Huntington’s disease would be positioned as a leader within the market. uniQure has already received breakthrough and regenerative medicine advanced therapy designations for AMT-130 from the FDA. The company plans to file for approval in early 2026, with the potential to bring the first disease-modifying therapy to Huntington’s patients soon after.

A New Chapter for Huntington’s

For people living with Huntington’s, even modest progress means everything. A disease once thought to be unstoppable may finally have a treatment that alters its natural course. Families who have watched loved ones lose speech, memory, and independence may now have reason for new optimism.

While Huntington’s is not yet curable, the success of this trial represents something families have long hoped for but never had: real evidence that science can not only ease symptoms, but actually fight back against the disease itself. It marks the beginning of a new chapter, one where hope is no longer just wishful thinking, but something grounded in data and possibility.