The Anthony Bourdain Reader (Bloomsbury) includes “An Exquisite Corpse”, the last, mordant, previously unpublished piece that the television star, bestselling author and acclaimed chef wrote before taking his own life in 2018, when he was 61. This collection features his fiction, essays, graphic novel articles and travel writing. Unsurprisingly, the book contains copious wild antics from a man who says that he spent 28 years “serving dead animals and sneering at vegetarians”.

His admirers will love the book and although there are plenty of entertaining moments, I wearied (after nearly 500 pages) of the repetitiveness of the shtick that underpins tales of a drug-addled past. I preferred his highly original reflections on life in restaurant kitchens. For instance, his quirky short essay “The Purpose of the Hamburger Bun” is spot on: the brioche roll is overrated – and bog-standard ketchup is better than artisan condiment sauce.

Mark Forsyth’s Rhyme & Reason: A Short History of Poetry and People (for People who Don’t Usually Read Poetry) demonstrates yet again that the patriarchy has long tentacles. First World War soldier poets such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon and Rupert Brooke have been fêted for more than a century, yet I was surprised to read in Forsyth’s book (Allen & Unwin) that of the roughly 2,000 poets published in Britain in the years 1914-1918, “there were more women than soldiers” and that “their poetry was what soldiers were reading in the trenches”. As Forsyth remarks, “they’ve almost all been edited out of history”.

Finally, my first Christmas present recommendation of the year is for Michael Hogan’s smashing debut novel, The Dogwalkers’ Detective Agency (Penguin). Hogan is a witty journalist, and his warm, waggish tale of a group of murder-solving canine owners in the sleepy coastal town of Framstone is ideal for a dog-loving book lover.

The choices for memoir, novel and non-fiction book of the month are reviewed in full below:

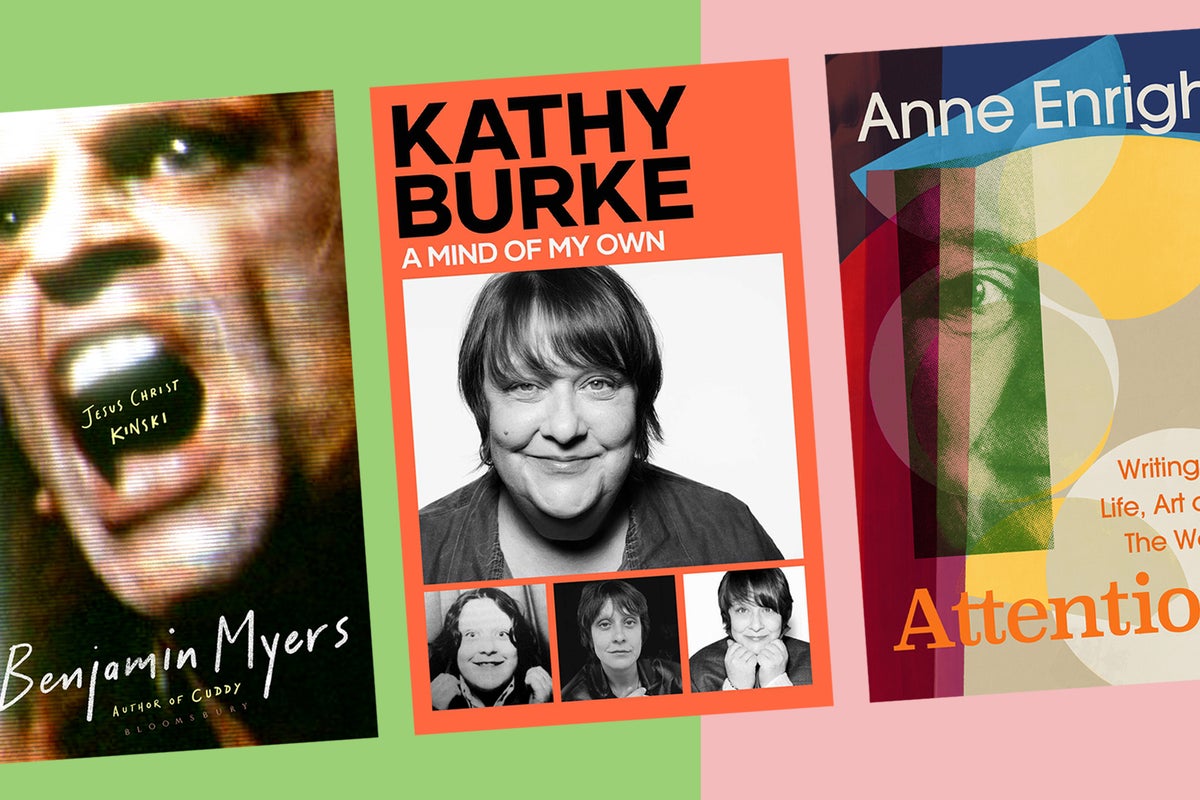

Memoir of the Month: A Mind of My Own by Kathy Burke

★★★★☆

open image in gallery

Kathy Burke’s memoir tells a revealing story of her class and her gender in a bygone time (Ian Rankin/Simon&Schuster)

Even though her exalted television characters Waynetta Slob and the teenage oik Perry are truly memorable creations, there is so much more to Kathy Burke than the recurring roles on Harry Enfield and Chums and French and Saunders that made her a household name. Not that celebrity matters to Burke, who dismisses being famous as “embarrassing”.

As I read the printed version of her memoir A Mind of My Own, it was easy to imagine the treat in store for those who listen to Burke’s own narrated audio version, especially when she reads aloud lines such as “walk, crunch, walk, crunch. Lovely”, the evocative way she describes the pleasure of spending the bus fare on crisps when she strolled home as a child. Burke is a London contemporary of mine. She was born in June 1964 in Islington – a mile or so from where I grew up, having been born that same summer – and her anecdotes of places such as Coram’s Fields, Chapel Market and “the dreaded Eastman Dental Hospital on Gray’s Inn Road” are accurate and amusing.

Burke’s mother Bridget died of stomach cancer at just 38, when the future actor was two, and she was raised by a father who was subject to frequent “drunken rages”. It is no surprise that Burke was naughty at school. There are touching stories of her path to acting success – sparked by gaining a place at the celebrated Anna Scher Theatre – which culminated in glory at the Cannes Film Festival in 1997, when she won Best Actress for her work in Gary Oldman’s Nil by Mouth. The story of collecting the prized movie trophy is an absorbing one, ending with “accepting a bellini cocktail from Harvey f***face Weinstein”.

Burke is equally blunt about some of the other people who have crossed her path – the actor Kerry Fox is recalled as a “charmless prick”, a harsh teacher is “a rotten old b****” – although the acerbity is balanced by her warmth towards the many kind souls she has encountered, including Rik Mayall, Donald Pleasence, Minnie Driver and Oldman.

The memoir, which tells a revealing story of her class and her gender in a bygone time, is as forthright as you would expect from Burke, who has never been afraid to speak her mind. One time, when she was performing in a show at Chelsea Army Barracks, she caused a rumpus among the soldiers by saying into the microphone, “Give Ireland back to the Irish.”

There are candid tales of her life in “straight acting” – including as a playwright and theatre director – and she also deals with her own mental health and addiction issues. She notes that when she confessed to fellow thespians about her psychological problems, a friend warned her: “Be careful, Kath, this business doesn’t like people being unwell.” The one area Burke is more guarded about is the turmoil in her private life; she brushes off the emotional scars of bad relationships by quipping: “The odd fling was more than enough.”

I went into the book expecting to like Kathy Burke and came out with a great deal of affection for this generous, unpretentious and shrewd person. Above all, what I really enjoyed about A Mind of My Own was Burke’s fiery spirit, which shines through in every chapter, including the one detailing her interactions with frontman of The Pogues Shane MacGowan. The singer only ever greeted her by saying, “Alright, stupid?” She was not cowed, though, answering, “Yes, thanks for asking, prick.” A mind and mouth of her own.

‘A Mind of My Own’ by Kathy Burke is published by Gallery on 23 October, £22

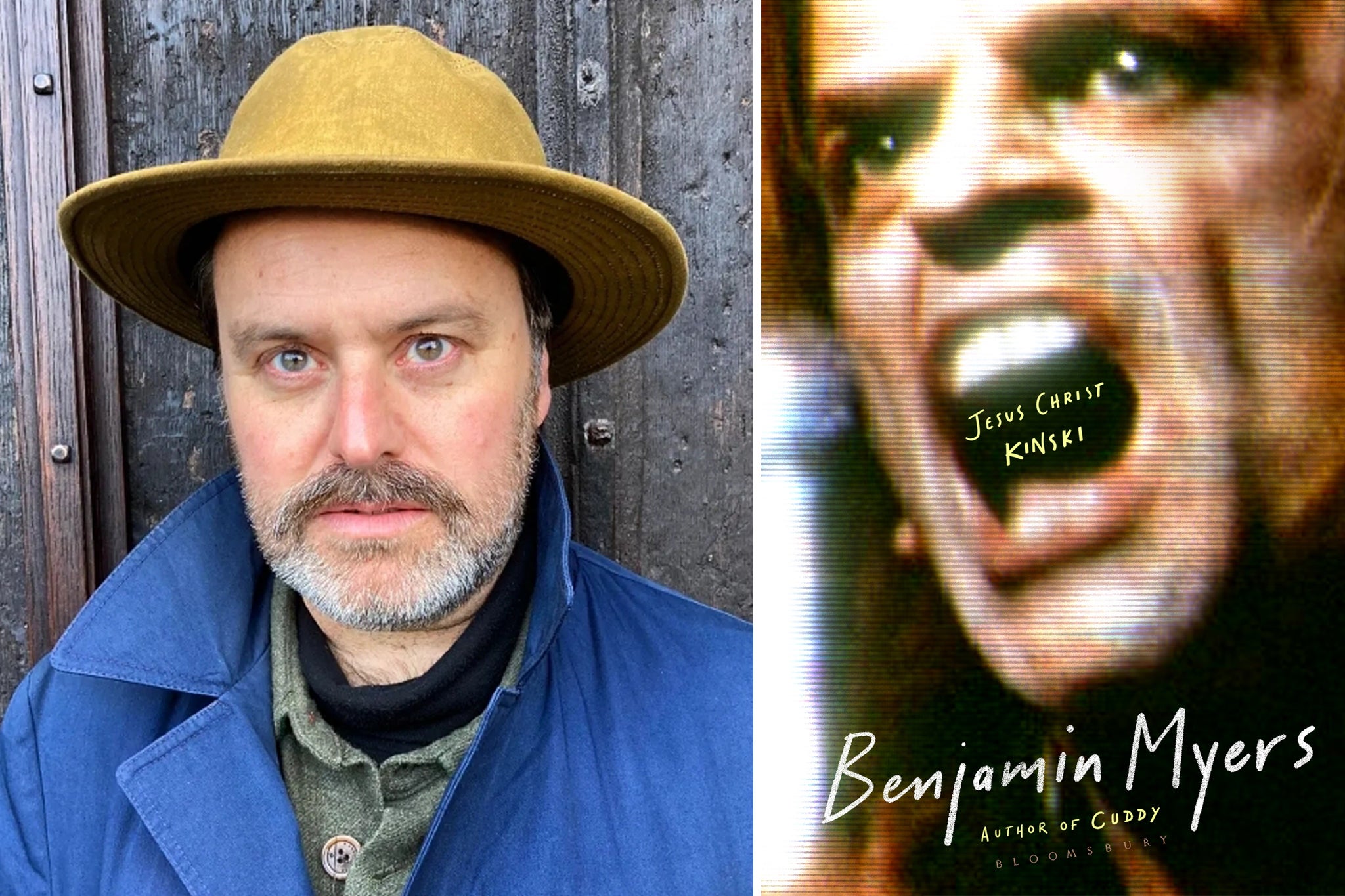

Novel of the Month: Jesus Christ Kinski by Benjamin Myers

★★★★☆

open image in gallery

Benjamin Myers serves up bold and inventive structure in his obsessively narrated novel (Bloomsbury)

The housebound writer who becomes obsessed by the late German actor Klaus Kinski in Benjamin Myers’s highly original new novel Jesus Christ Kinski, describes him as a “strange, blonde golem”, something that rings sharply true if you look closely at the 50 or so photographs of Kinski within the pages. His renowned actress daughter Nastassja must surely have gained her looks from her mother.

The novel centres around a one-man show Kinski delivered in Berlin in November 1971 about Jesus (“mankind’s most exciting story”), one that ended in tumult and which marked his end as a stage performer. Myers captures the dark and forceful energy of Kinski, who died in 1991, and his startlingly aggressive and vicious mind. The fictional recreation of his performance at Berlin’s Deutschlandhalle gives Myers the chance to imagine what was going on in Kinski’s head as he delivered his monologue.

Myers offers some respite from the fetid mind of Kinski in two sections about “the author”, set in West Yorkshire during the Covid lockdown. The writer, who has playful echoes of Myers’ own life, is the same age as Kinski was in 1971. The Kinski narrator muses on the morality of writing from the perspective of someone who “almost certainly abused women and children” (including, it was alleged, the German’s own daughter Pola).

This bold, inventive structure and content also give Myers the room to reflect on performance, censorship, mental health, loneliness, cancel culture and what we do with great art made by horrible people, especially in a 21st century in which people revert so easily to indignation.

Myers offers a stunning rendering of the intensity of the crazed Kinski, and although the book is bleak at times (because of his ugly personality), it is also funny. Kinski slates his theatre audiences as a bunch of farting, coughing, smelly, ignorant “sleepwalking bastards”. In one of his internal monologues, his Jesus complex is on full display as he muses that he is “up on the cross for this lot of s***bags”. The audience is presented as a vicarious entity in the novel, getting their kicks from seeing Kinski weep, seeing him broken.

Both Kinski and his “biographer”, housebound by winter snowstorms, reflect on the English character. While the 2021 author describes a “confused and sometimes cruel place called England”, Kinski in 1971 is scathing about a people who have perfected ways of masking their cruelty. “The English hide behind a false veneer of fairness and respectability… they are hypocrites who would slit your throat from behind at the first available opportunity,” he is quoted as saying.

Myers pokes fun at the writing process – “it’s just lonely people typing, punctuated by biscuits” – and his own character’s decision to pick such a “niche” subject for his fiction. The book works because Kinski makes a compelling subject for a novel, even if it’s hard to be convinced of his claims to genius. And despite the heavy subjects in Jesus Christ Kinski, Myers’s novel is much more fun than you might expect. One final tip: read right to the end of the unusual “credits”.

‘Jesus Christ Kinski’ by Benjamin Myers is published by Bloomsbury Circus on 23 October, £18.99

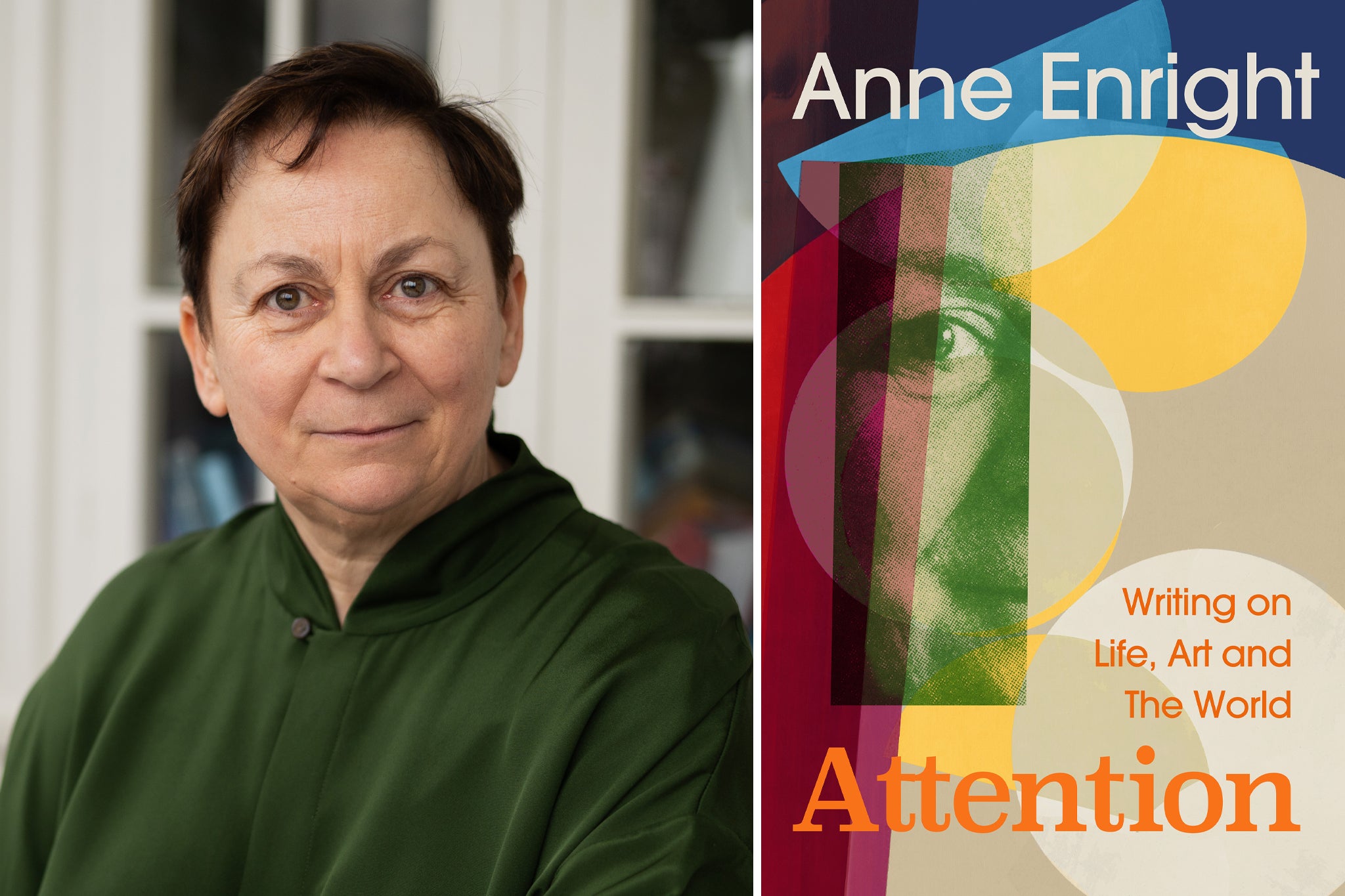

Non-fiction Book of the Month: Attention: Writing on Life, Art and the World by Anne Enright

★★★★★

open image in gallery

Booker winner Anne Enright’s literary pieces are full of sharp wit and disarming simplicity (Penguin Random House)

Dublin-born Anne Enright is a dazzling novelist – think of The Green Road, The Booker Prize-winning The Gathering, or Actress – and an insightful essay writer. Attention: Writing on Life, Art and the World brings together Enright’s wide-ranging cultural criticism, literary and autobiographical prose for the first time.

The literary pieces, in a section called “Voices”, include her assessments of titans such as James Joyce, Angela Carter, Toni Morrison and Edna O’Brien, and she brings an original perspective to her appreciation of their work.

The section called “Bodies” features her take on contemporary issues such as the #MeToo movement and abortion, and both articles are full of sharp wit and disarming simplicity. In “Time for a Change”, for example, written in 2018 about Ireland’s referendum on abortion reform, she cites that there had been 63,897 live births in Ireland that year, which she looks at in the context of a respected American study, which estimated that up to a quarter of pregnancies end in miscarriage. She adds, “which means that around 20,000 conceptions could have failed in Ireland last year due to natural causes. If all life is sacred, then all life did not get the memo.”

The most powerful section is “Time”, in which Enright explores her own Dublin upbringing, her marriage and several different periods of her life as a professional author. The highlight is “House Clearance”, a moving, wise piece of reflection on family mortality and nostalgia. Anyone who has had to empty a family home of their dead parents’ possessions will recognise the truth and pain in her account. “Every clearing day, the same fog sets in,” she writes.

I admire Enright’s fiction. Attention confirms the intelligence, compassion and humour of the mind behind the novels.

‘Attention: Writing on Life, Art and the World’ by Anne Enright is published by Vintage on 30 October, £20