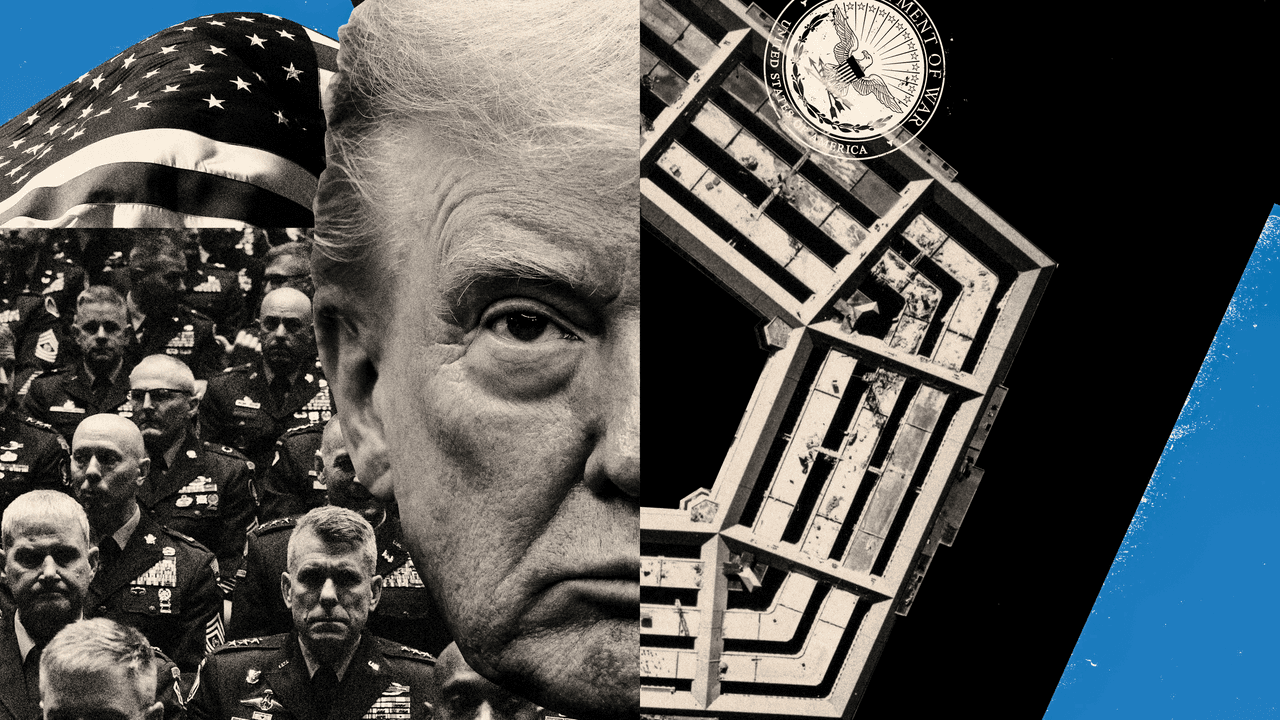

For someone openly campaigning to get a Nobel Peace Prize, Donald Trump has been going about it in an unusual way. Early last month, the President proclaimed in a press conference that the Department of Defense would thereafter be known as the Department of War. At the same briefing, the presumed new Secretary of War, Pete Hegseth, promised that the armed forces will deliver “maximum lethality” that won’t be “politically correct.” That was a few days after Trump had ordered the torpedoing of a small boat headed out of Venezuela, which he claimed was piloted by “narco-terrorists,” killing all eleven people on board, rather than, for instance, having it stopped and inspected. After some military-law experts worried online that this seemed uncomfortably close to a war crime, Vice-President J. D. Vance posted, “Don’t give a shit.”

So it felt fairly ominous when hundreds of serving generals and admirals were summoned from their postings around the world for a televised meeting on Tuesday with Trump and Hegseth, at the Marine Corps base in Quantico, Virginia. “Central casting,” the President said, beaming at the officers in the audience, who sat listening impassively, as is their tradition. He praised his own peace efforts, particularly in the Middle East, and mused about bringing back the battleship (“Nice six-inch sides, solid steel, not aluminum,” which “melts if it looks at a missile coming at it”), then issued what sounded like a directive. He proposed using American cities as “training grounds” for the military, envisioning a “quick-reaction force” that would be sent out at his discretion. “This is going to be a major part for some of the people in this room,” Trump said, like a theatre teacher trying to gin up interest in the spring musical. “That’s a war, too. It’s the war from within.”

Peace abroad and war at home? It was an unusual note to strike in an electoral democracy, even if recent reports had indicated that a draft National Defense Strategy would shift the military’s focus from Russia and China to domestic and regional threats. But though Trump keeps talking about his domestic military missions in a dramatic future tense, not much has been demanded of the ones deployed so far. In Washington, D.C., where troops were sent this summer as part of a supposed war on crime, they were seen picking up trash, painting fences, and finding lost children, while the arrests they initiated often led to trumped-up charges that grand juries rejected, in what the Times described as a “citizens’ revolt.”

When that offensive petered out, Trump turned his attention to immigration enforcement in the Windy City. (“Chicago about to find out why it’s called the Department of WAR,” he warned on social media.) Yet there has been an asymmetry between the Sturm und Drang of that operation—a midnight raid featured agents rappelling from helicopters onto a South Side apartment building—and its effect. Alderperson Andre Vasquez, who chairs the city council’s Committee on Immigrant and Refugee Rights, said that his office had not seen enforcement “to the level of what is being promoted by the President,” and reporters struggled to square government claims about the number of detainees with court records. Even so, the Border Patrol announced that a marine unit would be relocated to Chicago. “Lakes and rivers are borders,” an official said. With what, Michigan?

Cities do have problems, but no matter how much Trump wants to literalize the culture war they are not war zones. Memphis and Portland are next on the President’s list. But the generals and the admirals assembled at Quantico might have reasonably noticed a paradox: although Trump seems to want no restraints on what he can do with the military, he hasn’t yet articulated anything specific for it to do, other than make a show of reducing crime in places where the rate is generally already falling.

The call to Quantico initially came from Hegseth, lately seen staging a pushup contest with Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. At the Pentagon, Hegseth, who has few typical qualifications for his position, has largely focussed on a de-wokeification program, restoring the names of Confederate generals to military bases and, last week, rejecting efforts to revoke the Medals of Honor for soldiers involved in the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee. At Quantico, he declared that to instill a “warrior ethos,” a new promotions policy would be based on “merit only.” But it sounded like a pretty superficial idea of merit. “It all starts with physical fitness and appearance,” Hegseth said. He mentioned beards and fat (he’s against them) more than he did drones or missiles. “It’s completely unacceptable to see fat generals and admirals in the halls of the Pentagon,” he added. “It’s a bad look.” But does Hegseth want the best generals, or just the best skinny ones?

It’s interesting that the long tail of the misguided wars in Iraq and Afghanistan should wind its way here, to a militaristic right-wing President who loudly denounced those foreign conflicts but means to treat American cities as war zones, and to a Defense Secretary who wants to do away with rules of engagement. Among the defense community, the reaction to the Quantico speeches was an extended eye roll. “Could have been an email,” an anonymous senior official told Politico. On Tuesday, the White House announced that troops would be sent to Portland to “crush violent radical left terrorism.” That sounded much more frightening than the policy details reported by Oregon Public Radio: two hundred National Guard troops would be sent to provide additional security at federal facilities. For now, there is a heavy element of make-believe in the President’s domestic military ambitions, which, as was the case with the now greatly diminished doge project, allows him to pretend that he wants a major substantive change when what he really seems to want is more power.

On Wednesday, in Memphis, the White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller told a group of deputized federal officers, “You are unleashed.” That same day, the President’s lawyers asserted in a letter to Congress that the country is now formally in an “armed conflict” with the drug trade broadly, a determination through which Trump can claim extraordinary wartime powers. (There have been three more lethal attacks on boats in the southern Caribbean since early September, the most recent on Friday.) Each of these steps has elements of military theatrics and cosplay authoritarianism, but the more the White House insists on the trappings of war—the troop deployments, the “warrior ethos” grooming, the emergency legal powers—the more it risks nudging us toward an actual one. ♦