As a child, Eli Robinson liked his noodles covered in ketchup. So his younger brother Duncan did, too.

“Disgusting in hindsight,” Duncan Robinson said. “But there was legitimately a three-month stretch where I tried to convince myself and others that I actually liked that, because that’s what he did. I just wanted to be him.”

It was why when Eli became interested in animals, that passion became Duncan’s, too.

“Steve Irwin,” Duncan said, “was like our LeBron James.”

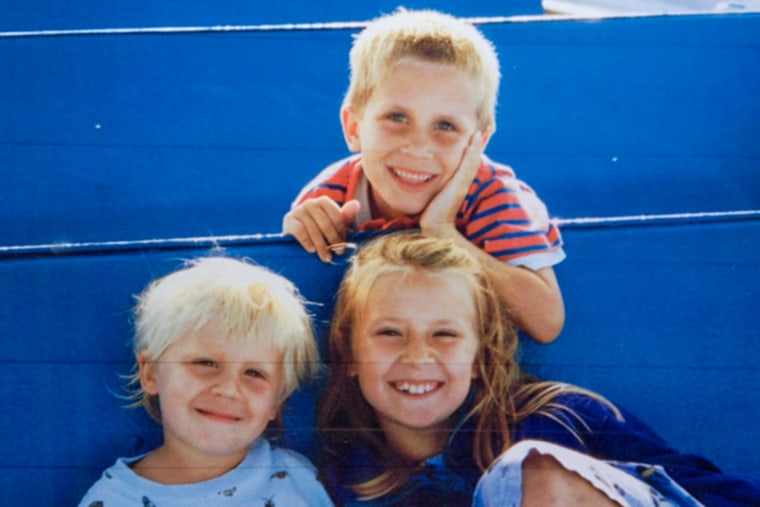

In grade school, their shared obsession turned toward basketball. Born 3½ years apart, the brothers overlapped one season as high school teammates near their home in New Castle, New Hampshire. As Duncan traveled an unlikely route from playing in the smallest division in the NCAA to the NBA, where he, now 31, plays for the Detroit Pistons, Eli proudly declared himself Duncan’s biggest fan, said Marta Robinson Day, the oldest of the Robinsons’ three siblings.

Eli Robinson.Courtesy Robinson family

Eli Robinson.Courtesy Robinson family

But in recent years when Eli would call his family — sometimes dialing Duncan more than a dozen times before and after games during his first seven seasons in the NBA — they didn’t know what to expect to hear on the other end.

Eli heard voices. The auditory hallucinations, diagnosed in 2021 as schizophrenia, turned the big-hearted, caring side of his personality his family loved into a hypervigilant, protective paranoia that his parents, Elisabeth and Jeffrey, tried to de-escalate. As a last resort, they would call in Marta, a licensed therapist, and Duncan, who was Eli’s “whisperer.”

The voices were “all about us being in danger,” Marta said.

Duncan said: “The real challenge of that was the volatility. He would call me, he would make sure I was safe. He made sure I was OK. … And then he could hang up. And sure enough, maybe, you know, 15 to 20 minutes later, he called me again.

“So of course, in that stretch, I think, probably the greatest challenge was finding ways to compartmentalize and still try to perform. I always kept in perspective, like he’s the one going through it. And obviously it impacts us as a family. We were all sort of constantly anxious and on edge, but that was never the priority, making sure we were OK. It was always making sure he was OK.”

It wasn’t his first battle. Using marijuana and alcohol in high school made Eli a “runaway train” of addiction, said his mother, Elisabeth. When he became sober in 2021, at 31, it was a breakthrough; he wore a sobriety necklace and talked proudly about his recovery. He split time living at his mother and father’s homes, and held down a job at a pizza shop. He adored Marta’s daughter, Gemma, and kept close tabs on Duncan’s first seven seasons with the Miami Heat.

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

But the two dozen medications he tried, the 16 times he was admitted for psychiatric hospitalizations or the 30 rounds of electric convulsive therapy he completed couldn’t keep the voices away.

On April 30, Eli, 34, climbed the Piscataqua River Bridge, which connects Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to Kittery, Maine, and jumped, dying sometime after he landed in the river below.

“The goal is to turn this pain into progress,” Duncan said, “and do it in a way that Eli’s name is remembered.”

One way is by launching the Robinson Family Foundation, in part to use their connections and experience inside the health care system to help others dealing with mental health issues. It is part of what they call their challenge to “live like Eli lived,” Robinson Day said. In the same way Eli was frank and open about his sobriety and his schizophrenia, his family is now speaking publicly about his life and death in ways that Duncan, a self-described private person, would typically have been reluctant to do.

But he knows Eli would have. And so, he is still following his older brother’s example.

‘What do we do next?’

Eli once asked his mom for a favor. Housing for five of his pizza shop co-workers had fallen through. Could she put them up temporarily?

They lived with her for five months.

“He loved helping people,” she said.

But often he couldn’t help himself. His family was uniquely positioned to assist.

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

Marta is a licensed mental health counselor who has trained in emergency mental health assessments. Elisabeth is family nurse practitioner. Their experience, connections and financial resources were primed to help Eli and allowed him access to top care at facilities that, in one case, could cost $1,000 per day, Marta said. Elisabeth believes a tainted strain of marijuana led to his schizophrenia, saying there is no other genetic history.

“It was always this hope, hope, hope,” Elisabeth Robinson said. “After his first [electric convulsive treatment], I talked to him, and I just started sobbing, because I felt like this is maybe it. This is maybe the help that we needed. And then, you know, three weeks into it, he came one morning, and he goes, ‘The voices are back.’ And I was just crestfallen, not for me, but for him.

“And, OK, what do we do next? Where do we go? What do we do?”

In 2021, after he became sober, Eli lived in a Florida residential facility that specialized in patients with dual diagnoses. Duncan, who spent his first seven seasons with the Heat, would visit on days off during the NBA season or after practice.

“It was this weird juxtaposition that I was sort of living my dream, really our dream, because it’s what my brother wanted, too,” he said. “And then going 35 miles up the road and seeing this totally different experience of what my own flesh and blood, you know, my big brother was going through.

“Those are really some of the most challenging aspects in years for me, because he was so close. But in reality, it felt like he was so far. I would try to always have these points of contact, but it was really hard.”

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

Yet even the Robinsons’ advantages didn’t allow them to easily navigate what they described as a disjointed health care system, in which communication between providers regularly broke down. They created a 10-page document outlining every step of Eli’s past care and treatments and found themselves repeating it at every new stop. The lack of continuity was “one of the most frustrating aspects,” Duncan said.

The family plans to use its foundation to help other families avoid such potholes in the health care system as part of a broader goal of addressing mental and heart health and physical well-being. They envision offering grant-based help. After Eli’s death, the family pointed donations toward Seacoast Mental Health Center, where Eli had received treatment. More than $120,000 has been raised, said Kelly Hartnett, the center’s vice president of community relations.

“So many people don’t have access and are getting lost in translation in the system,” Hartnett said. “How can the Robinson family use their platform to talk about this? I think it’s huge.”

The family is also advocating for deterrents to be added to local bridges. Two weeks after Eli’s was one of three deaths by suicide from local bridges within a 24-hour span, signs that included a suicide-prevention help line were installed on the Piscataqua River Bridge.

Eli Robinson plays with his niece.Courtesy Robinson family

Eli Robinson plays with his niece.Courtesy Robinson family

In June, New Hampshire Gov. Kelly Ayotte created a task force to address how to prevent more deaths. Hartnett, a member of one of the task force’s subcommittees, said the group has commissioned an engineering firm to study the feasibility of installing fencing or netting, and it is also exploring increased monitoring of existing bridge cameras. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention recommends such physical barriers, saying they can “act as a delay and deterrent to an individual at risk, providing more time to get through the intense, often brief, moment of suicide crisis.”

Eli had encountered such a moment six months before he died. On Oct. 27, 2024, he climbed the Piscataqua River Bridge and jumped for the first time. When he woke up from a medically induced coma in early November, Marta and Duncan, who had missed a game with Miami to visit the hospital, believed they saw a change.

“‘I’ll never do that again,'” Eli said, Marta recalled. “Because Duncan and I were both sobbing by his bedside. He said, ‘I absolutely promise.’ We all felt that. We all really believed that.”

‘A gift to us’

In 2018, during the middle of All-Star weekend, one of the NBA’s highest-profile events each season, the All-Star guard DeMar DeRozan sent a tweet acknowledging his depression. Other players saw the admission from one of the league’s best players as permission to talk about their own struggles with mental health that come from a job that can be one of the country’s most public and scrutinized. The league and its players union now offer an array of mental health services.

Robinson, though, said he didn’t feel comfortable making his brother’s struggle, or how it had affected him, widely known beyond a small circle within the Heat. He was concerned such a disclosure might “embarrass” Eli, saddle teammates with a burden they hadn’t asked for or leave team leaders questioning his professionalism or on-court focus. Compartmentalizing meant turning his phone off 90 minutes before tipoff.

In a similar way, his mother said, the family often tried to shield Eli’s siblings from as much of his struggles so as to not affect their careers.

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

The Robinson family.Courtesy Robinson family

“I do think I always gave myself permission when it got to a point that I could no longer bear that I found a way, an outlet, somebody to talk to,” including the woman who is now his fiancée and outside therapists, Duncan said.

Eli, however, couldn’t so easily cut off voices from reaching him. It led his parents and siblings to brace for the worst when they saw him calling — and when he hadn’t checked in, too.

“Eli was not depressed. Eli loved life. Eli had a lot of relationships,” Duncan said. “Eli cared about his family, his people, more than anybody. Eli was tortured. Eli had a disease that he couldn’t shake, and he fought incredibly valiantly. And I think you know, as his family and the people closest to him, I think we all understand.

“Doesn’t make it easy; makes it still incredibly hard. But it wasn’t that he was this person that was waking up every day saying, ‘I hate life, I hate this’; no, it was he just couldn’t do it anymore. … I mean, imagine doing mundane tasks, driving to work, doing that, and just being entirely tortured, having voices in your head all day long. And he just had enough.”

His family doesn’t want him to be remembered for what he heard. Instead, they say, they want to keep alive the way he used his own voice to ensure strangers and family members were safe and address stigmas of addiction and mental health straight on. Strangers have sent Elisabeth and Marta letters thanking them for sharing Eli’s story.

Duncan and Eli Robinson.Courtesy Robinson family

Duncan and Eli Robinson.Courtesy Robinson family

“Being honest about the struggles that we had with him has him continue to live in our hearts, and that’s a gift,” Elisabeth said.

When Eli was alive, it was easy for Duncan to champion his brother’s sobriety, his sister said. He was less comfortable, she said, discussing the schizophrenia diagnosis. In recent months, she has seen that change.

This summer, Duncan went public about Eli’s death for the first time by posting a video to his Instagram page — under his handle, @d_bo20, a childhood nickname Eli used for him. Talking publicly about it “isn’t about me and the challenges that come with that,” he said.

“There were so many incredible moments where he won those battles,” he said. “So I just want to acknowledge those.”

Duncan is still modeling himself after Eli. The sobriety necklace Eli wore proudly now belongs to his younger brother. He wears it every day.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 or go to 988lifeline.org, to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. You can also call the network, previously known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, at 800-273-8255 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.