It has been 76 years since “1984,” George Orwell’s warning about government control, censorship and the corruption of language, was first published.

The organizations behind Banned Books Week based this year’s theme, “Censorship Is So 1984. Read for Your Rights,” on Orwell’s sobering story to show we may be closer in real life to his dystopia than ever before.

Over 3,700 unique books were banned during the 2024-2025 school year, more than double the number of titles advocacy group PEN America tracked in the 2021-2022 school year when it began counting. The nonprofit, dedicated to free expression, found 6,870 total instances of book banning in the ’24-’25 year. Their “Banned in the USA” report warns against a “normalization” of book bans, calling them “rampant and common.”

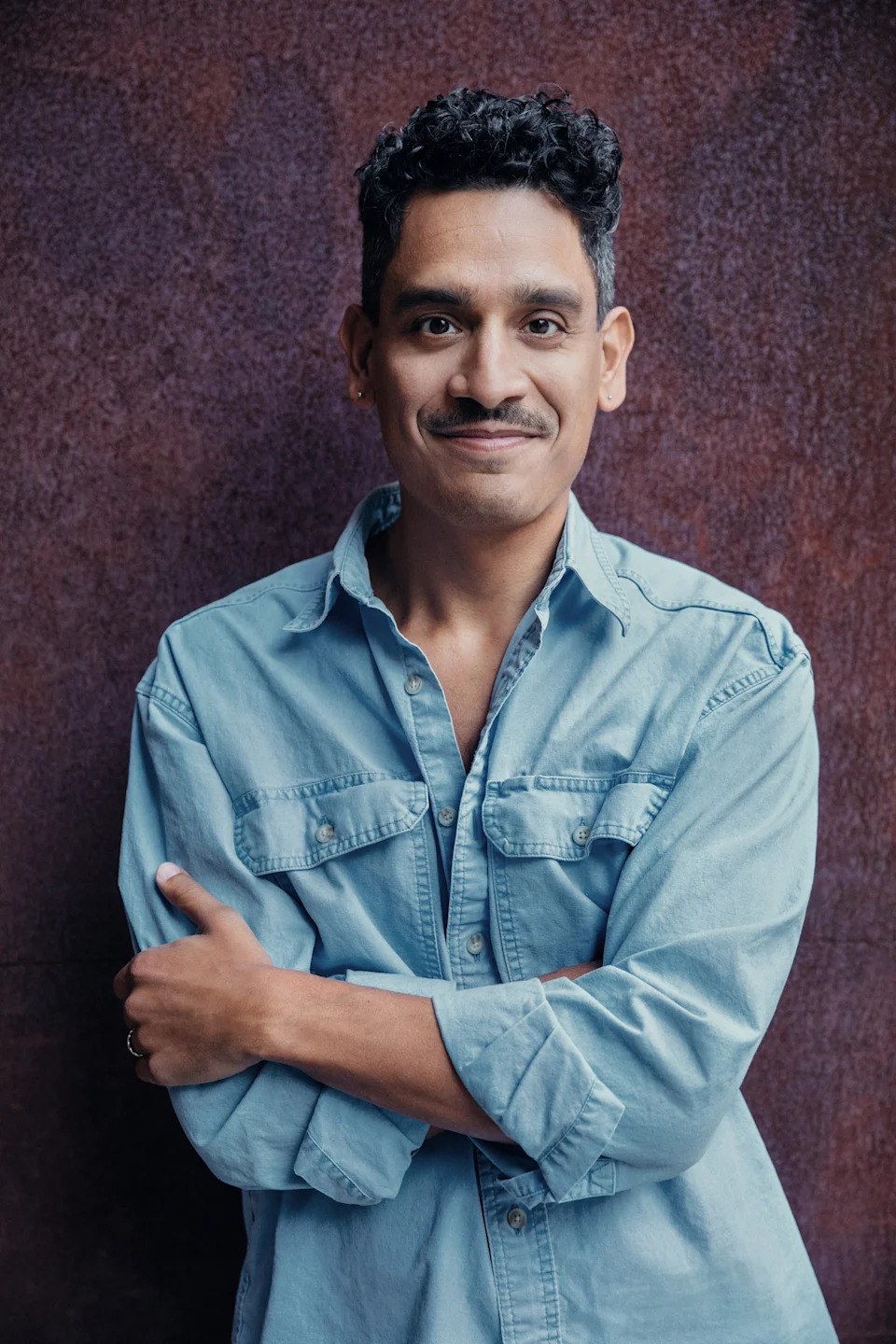

“If we’re not careful, it might not simply be your book being put on a list that makes it so a librarian can’t order it,” says Clint Smith, author of “How the Word Is Passed.” Instead, “it might be you arrested for writing the book in the first place.”

The theme of 2025’s Banned Books Week is “Censorship Is So 1984. Read for Your Rights.” Some say it feels like a sobering reminder that we may be closer to the “1984” author’s dystopia than ever before.

“You have to recognize that where we are now is worse than where we’ve been, but where we could be going could be far worse than where we are,” the author adds. “That is why it’s so important to name it, to call it out, speak out against it as much as we can.”

In their own words, five writers − Professor Laura Beers, Chicana writer Sandra Cisneros, Professor Michael Shelden, fiction writer Alejandro Varela and Smith − recalled the impact of reading Orwell’s “1984” for the first time. They also explore whether we can outrun the parallels between our current political moment and Orwell’s world, as well as their interpretation of what’s actually considered “Orwellian.”

You’re using the term ‘Orwellian’ wrong. Here’s what George Orwell was actually writing about in ‘1984.’

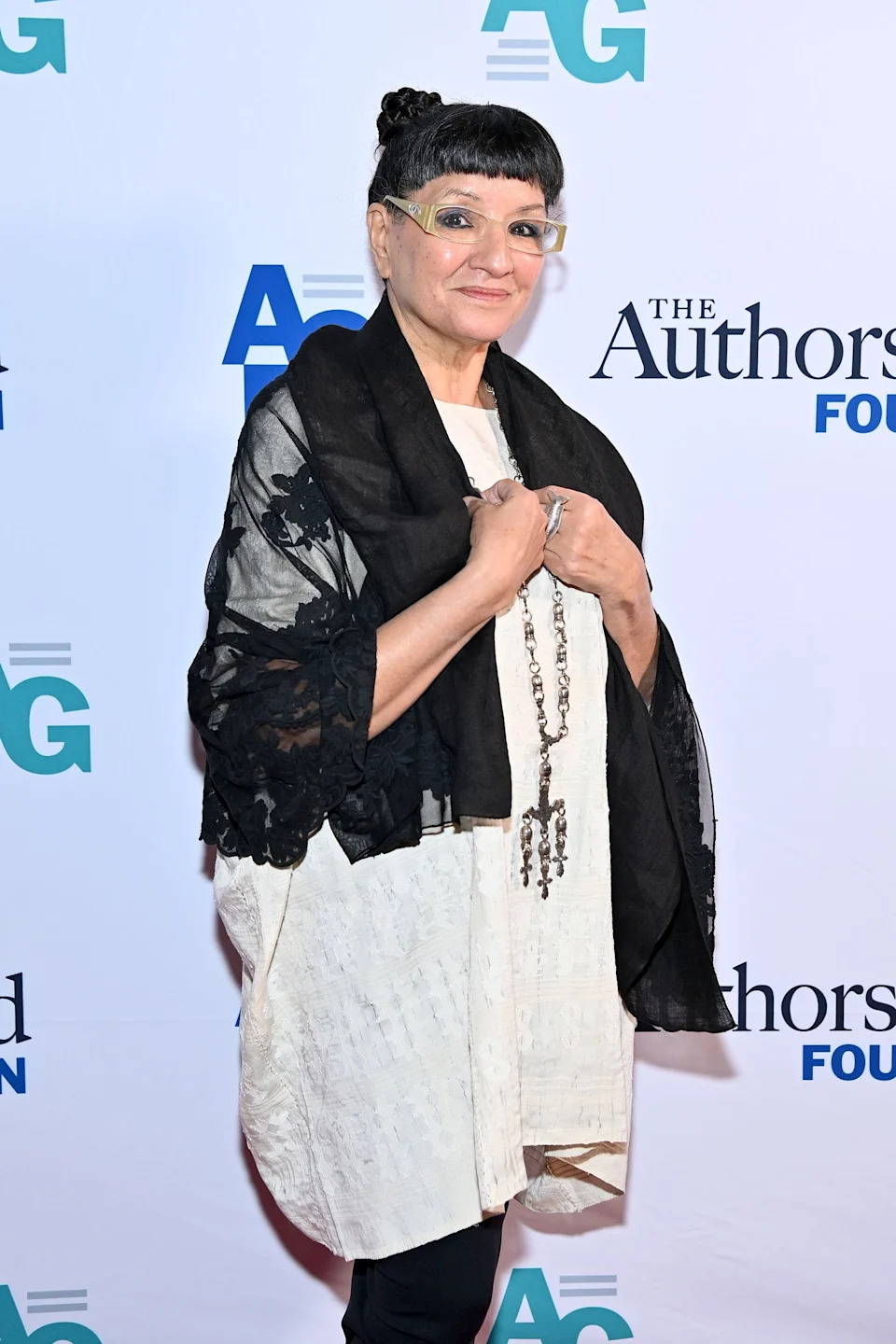

Beers penned 2024’s “Orwell’s Ghosts: Wisdom and Warnings for the Twenty-First Century” and Shelden authored 1991’s “George Orwell: The Authorized Biography.” Cisneros, best known for her work in “The House on Mango Street,” has seen her 1984-published novel challenged and banned in schools.

Reading George Orwell’s ‘1984’ for the first time

Question: When were you first introduced to Orwell’s “1984” and what were your thoughts on it at the time?

Beers: I first read “1984” in high school. At the time, it was in the mid-’90s and Orwell was still someone I thought of as a Cold War writer. I had read “Animal Farm” in middle school, in the last days of the Soviet Union. So he was presented as someone who was writing about censorship, repression, tyranny and restrictions on freedom of speech and freedom of thought.

But the context in which I was introduced to him was, “These are bad things that happened in the evil empire of the Soviet Union” … Orwell was concerned about censorship and the lack of freedom of thought and expression in the Soviet Union − but not exclusively in the Soviet Union. He was also very concerned about the sense of censorship at home in the British Empire. I see him as a critic of the tendencies towards censorship and totalitarianism everywhere − both at home and abroad.

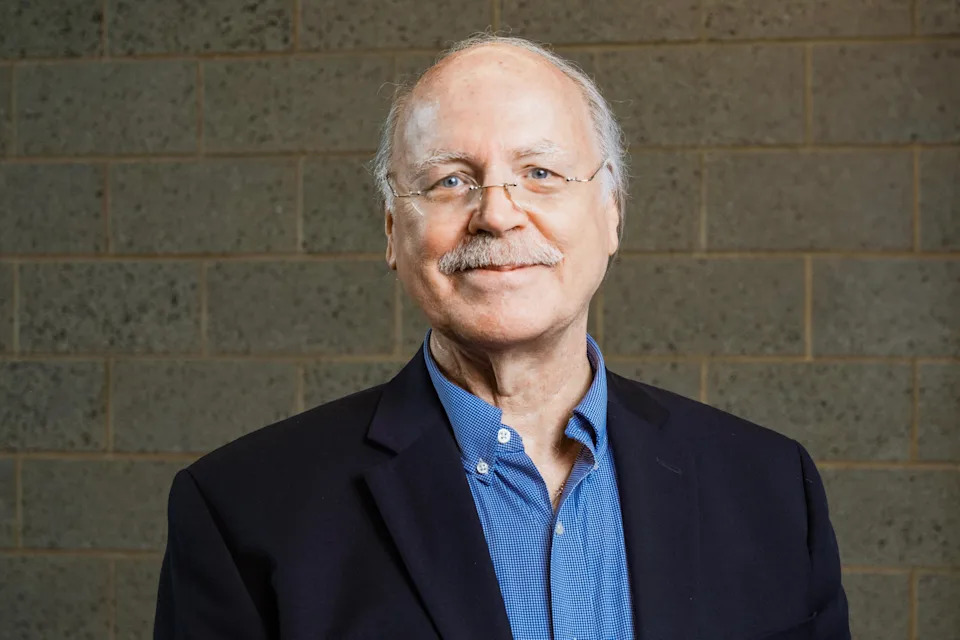

Shelden: It was more than half a century ago, and at that time, the great enemy was considered to be the communist bloc and the Soviet Union. I thought Orwell had a broader target in mind. He wasn’t just thinking of criticizing the censorship policies in the Soviet Union, but in all societies that pretended they could somehow control thought.

It has been 76 years since “1984,” George Orwell’s warning about government control, censorship and the corruption of language, was first published.

Smith: I first read the book in high school, and it seemed like something that could not happen here. I recognize now part of why it felt back then that what happens in “1984” could not happen here in contemporary America was because I did not learn about America fully. When I learned about American history, I wasn’t taught about how fragile this project, the American project, was. I was not taught about the three-dimensionality of America, about the complexity of America, about the contradictions of America, and about the ways that so many of what maintained our institutions were norms rather than laws.

Author Clint Smith published the 2021 book “How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning With the History of Slavery Across America” to critical acclaim, receiving the National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction. In 2023, he published the poetry collection, “Above Ground.”

In some ways, it feels incredible to have read that book and not to have seen the way that what was described might make its way here to the US. Because if you study American history, and if you study world history, you see that all of these democracies, all of these experiments, can be toppled by just a handful of people.

Is 2025 the new ‘1984’?

Question: What parallels do you see between Orwell’s world and the current debate surrounding literacy, books, education and access to information in the US?

Beers: Orwell talks about explicit censorship, but also about how language is controlled so that there are things you can’t say, and if there are things you can’t say, then there are ideas you can’t think. He’s very conscious about the connection between freedom of expression and freedom of thought because, without freedom of expression, you really can’t have freedom of thought. We can see those parallels within our society in how the current administration focuses on language, what can be taught in schools and what can be said on the airwaves.

There’s a real irony that just a few years ago, it was the political right that was decrying censorship and cancel culture was a major problem with the left. Now, you see the government in power trying to effectively exercise its own forms of censorship and cancel culture on views it does not agree with. That would not surprise Orwell, right? He believed that any political ideology was susceptible to this tendency towards tyranny − that it was just the fact that accretion of too much power could lead to these tendencies to suppress, dissent, and to maintain absolute control and to silence your opponents.

Shelden: In all of Orwell’s work, he’s looking at the attempt by larger powers to control the way that a population thinks, not just the way that they speak or write, but the way that a population thinks, which is far more dangerous than just trying to censor individual speech or censor a book. You’re trying to basically get people to censor themselves. We are in that world right now, we’re in a world where both sides of the political divide, it’s generally acknowledged that most people are censoring themselves to some extent by not speaking more plainly for fear that they will somehow offend either just other people or perhaps, worse, the powers that be (and) offend the people who could make them pay for their free thought.

Michael Shelden, a Dean’s Research Professor at Purdue University, is the author of six biographies, including “Mark Twain: Man in White” and “Orwell: The Authorized Biography,” which was a Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. He earned his Ph.D. from Indiana University.

Smith: What we have to recognize is that it can get much worse than it is now; we have to take that seriously. Again, all you have to do is study history to see how government efforts to surveil, control and propagandize only increase over time − if not met by fierce resistance from the public. We have to recognize that how we conceive of books being banned and challenged today is bad, to be sure, and that it can also get much worse. We can experience a much more draconian version of what we’re already experiencing if we’re not mindful, if we’re not forceful against these efforts, if we’re not speaking up against these intentions to prevent certain ideas, certain types of writers, certain types of people from having their work read and heard and engaged with.

What does it mean for something to be ‘Orwellian’?

Question: The term “Orwellian” has seen an uptick in its use for years before 2025. But does it feel truly more resonant today than in past decades?

Beers: Orwell was talking about the power of the state. The really repressive power of the state to stop alternative ideas from coming into circulation, from being debated and from having the chance to build their case. Being taken off Twitter is not Orwellian because you can set up Truth Social or an alternative platform, or your voice can be heard in other spaces. Having your book not be published because a publisher thinks your politics don’t align with theirs − assuming that there’s a marketplace for ideas and you can have your book published elsewhere − is not really Orwellian either, right?

Professor Laura Beer is interested in the ways in which politics both influences and is shaped by cultural and social life. In 2024, Beer published “Orwell’s Ghosts: Wisdom and Warnings for the Twenty-First Century,” where she explored the continuing relevance of Orwell’s writing for understanding the current political landscape.

Orwell was thinking about a society where people who spoke out were jailed, potentially executed and were kind of disappeared. That is his specific dystopia. We are increasingly seeing a political world that could actually be described as Orwellian, where there is real existential risk for a lot of people in voicing ideas and exercising speech. They can lose their right to reside in the US if they are not citizens, they can lose their job, they can end up in prison. This is really, I think, the type of repression that Orwell is pointing at more so than just social media cancellation.

Shelden: When people use the word Orwellian today, I think they’re trying to indicate that there’s a frame of mind that is very willing to make you pay for saying something that is out of the mainstream or not popular, or in some ways, attacks or challenges the status quo. The reason that’s so dangerous, and what Orwell is trying to show in the dangers he did show in “1984,” is that a society that doesn’t have free thought doesn’t have anything.

You don’t have innovation, you don’t have dissent. It isn’t just politics that suffers. It’s everything from religion and faith to just social life in general. When you can’t feel free to speak your mind, you might as well not have a mind, right?

Smith: While it is true there are always examples of Orwellian conditions in various spaces in society. It’s a question of scale and scope, right? It is both true that throughout American history, we have experienced, to varying degrees, and various communities have experienced more so than other communities, extreme government control, surveillance, propaganda and manipulation of the truth. The Lost Cause after the Civil War ended was Orwellian. The ways Black people were prevented from gaining the right to vote in the South by having to count the number of jelly beans in a jar and all sorts of absurd, insidious tests that were to see whether or not they could participate in the voting process, that is Orwellian.

But what’s also true is that we are living in a moment in which the most dangerous forms of surveillance, government control, propaganda, and the erasure, distortion, or manipulation of the truth are omnipresent in this country. It’s coming from the very top in ways that do feel new. You can both say there have been examples of Orwellian realities throughout American history and also recognize that we are at a fundamentally different point in this moment.

Author and public health worker Alejandro Varela is the son of immigrant parents from El Salvador and Colombia. He has authored 2022 “The Town of Babylon,” 2023’s “The People Who Report More Stress” and 2025’s “Middle Spoon.” His work takes on public health topics from systemic racism to gentrification and sexuality.

How Orwellian tendencies, book bans affect young readers

Question: How do you think the proliferation of book bans will impact future generations?

Beers: I’m a mother of two kids, one of whom is a boy in middle school, so I’m conscious every day of just the importance of reading. Of reading books, not articles that appear on your phone, but long-form writing, and particularly fiction, which has a unique ability to open your mind and take you into alternative realities and let you feel empathy for people who aren’t like you. That’s something we don’t want to risk. It’s difficult enough to get young people to read, or really, anybody, to read any kind of book anymore. We don’t need to make things harder by banning texts.

Varela: A lot of it is a perverted take on Judeo-Christianism or Christianity in which they think children shouldn’t be exposed to absolutely anything, and they have to remain pure at all times. But let’s not forget, we’re talking about a lot of people in this country who feel completely and totally disempowered, who fall into racism and classism and homophobia, and fall into all of these forms of discrimination. But guess where they do have power, or where they wish they had power? They have it in their children. They don’t see their own children as people that they have to (guide) through this world so that they can be productive in society.

Chicago native Sandra Cisneros is best known for her first novel, “The House of Mango Street,” which was published in 1984. Her novel has been challenged and banned in different states in the past.

It just continues to create this divide between those of us who are walking through this world with our eyes open and those who live in fear of all sorts of change and differences, who instead of celebrating a difference or seeing it as something beautiful, interesting or something to learn about, see it as a barrier, something to be afraid of and something that’s going to damage you.

Cisneros: It is important to understand, are the books even being read that are being banned? I don’t think so. When you ban a book, there’s something you’re afraid of (and) I really censored my book when I wrote it because I was aware that children might be in the room, so I wrote it in such a way that anything sensitive would go over their heads. I took special care to do this … because I wanted the book to be available in libraries.

There are a lot of things in libraries and bookshelves that people don’t want their children to read, I understand that. Parents have the right to police what their children can view or read. I understand that, too, but just because it doesn’t appeal to you doesn’t mean that it’s not necessary for someone else. You don’t burn down the pharmacy just because a book isn’t your prescription.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Authors explain Orwellian, why censorship could get ‘much worse’