Hamilton hospitals have lost track of thousands of doses of highly addictive opioids in recent years.

Exclusive data obtained by The Spectator shows more than 1,900 tablets, pills, vials and ampoules of controlled drugs went missing from Hamilton Health Sciences and St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton sites between January 2020 and April 2025.

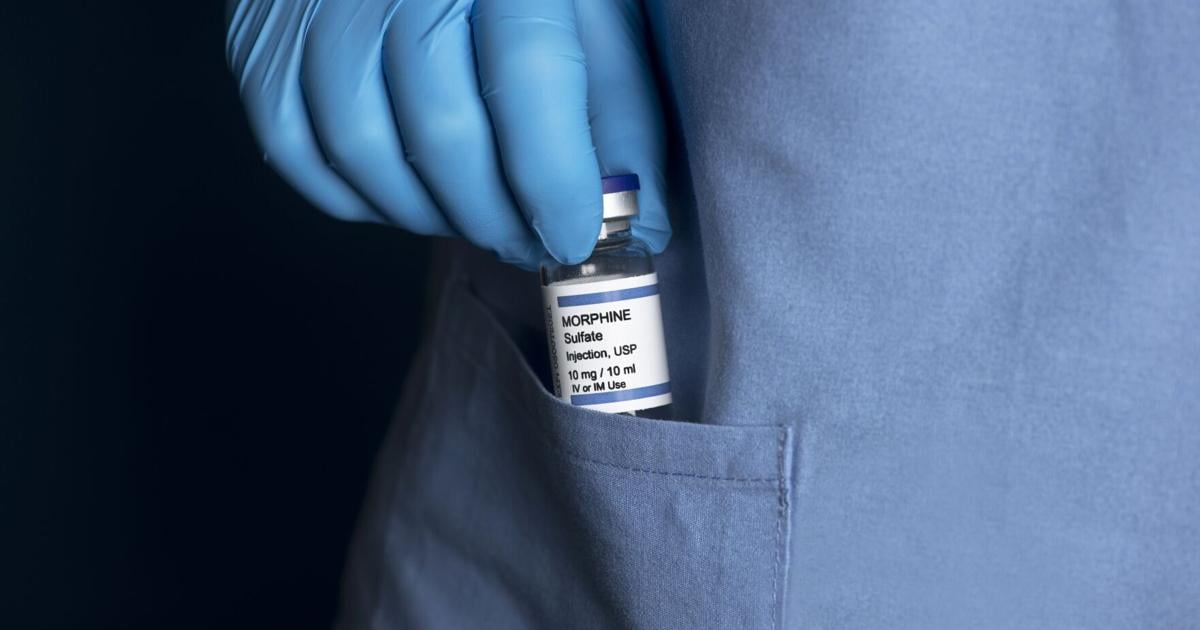

It’s part of a growing countrywide problem known as drug diversion, which experts say puts patient safety at risk, undermines trust in health-care systems and fuels addiction.

The disappearances in Hamilton also come as the city grapples with an opioid epidemic that has left hundreds of people dead this decade.

Of the roughly 7,800 milligrams in drugs that went unaccounted for at HHS and St. Joe’s between 2020 and 2025, more than 95 per cent cent belonged to a class of opioids used to treat chronic and severe pain, including hydromorphone, oxycodone and morphine.

A growing problem inside hospitals

According to The Spectator’s analysis of the five-year data set, which was obtained via multiple freedom-of-information requests, half of the vanished drug haul at local hospitals was reportedly stolen.

The Spectator’s analysis found most drug-loss reports at Hamilton hospitals were classified as “missing” rather than confirmed thefts.

The Associated Press file photo

That includes two significant thefts at HHS facilities in 2024, when hundreds of milligrams of opioids disappeared over several months in an emergency room and a specialty unit.

Data shows the complex care unit at St. Peter’s Hospital lost 280 Percocet pills and 138 hydromorphone tablets of varying strengths between December 2024 and March 2025.

HHS described the losses in a data sheet as “diversion noticed over four months involving (a) nurse on unit.”

The same description was given for the roughly 400 mg of liquid hydromorphone, stored in 200 sealed glass capsules, that was stolen from the emergency room at Hamilton General Hospital between April and October 2024.

What happened to the missing drugs or the involved nurses is unclear.

HHS cited employee privacy and refused to comment on the cases when asked if staff were disciplined or police were contacted.

Reports of missing drugs in Canadian hospitals or pharmacies must be filed to Health Canada within 10 days and include a reason, like spillage or theft. Health Canada defines drug diversion as health-care workers redirecting medication from its intended destination for personal use, sale or distribution to others.

HHS and St. Joe’s operate more than a dozen facilities across the city and employ thousands of people. Cases of diversion are rare relative to the millions of doses of drugs they dispense each year.

Between 2020 and 2025, the health-care networks filed only 131 individual drug loss reports to Health Canada.

Twenty-seven of those were attributed to theft — including 21 at HHS.

In August 2020, HHS reported three incidents of theft at Hamilton General Hospital involving three vials of liquid fentanyl, hydromorphone and morphine.

A few months later, in November of that year, Hamilton General Hospital experienced another 10 cases of thefts, with HHS reporting multiple forms of hydromorphone — 20 tablets and more than a dozen vials of varying strengths — seven oxycodone pills and two morphine injections as stolen.

More losses in recent years

While HHS has filed fewer missing drug reports to Health Canada than St. Joe’s in the past five years — 58 to 73 — the former outpaces the latter when it comes to quantity of lost drugs, with 1,162 tablets, pills, ampoules and vials (about 5,300 mg in total) reported missing or stolen compared to 755 (about 2,500 mg total) at St. Joe’s.

Much of the losses at HHS have come in the past two years. The network reported 486 units of missing or unaccounted for drugs in 2020 before a lull in 2021, 2022 and 2023 saw just 31 units disappear over three years. Since 2024, they’ve reported 648.

“Drug diversion, while rare, is a known risk within the health-care sector,” HHS said in an emailed statement, adding it couldn’t comment on specific cases — such as the thefts — due to employee privacy and confidentiality. “We take this issue seriously and have robust safeguards in place to prevent and detect it.

“This includes the use of automated technology to track and measure controlled substances and flag unusual patterns. We also follow strict policies and procedures that align with regulatory standards to guide our response to any suspected diversion.”

The fact that more than a third of reported drug-loss incidents at HHS were attributed to theft, rather than just missing or lost, is unusual.

Research on drug diversion in Canada suggests most drug losses are reported as missing without explanation.

Between 2015 and 2019, for example, hospital pharmacies in Canada reported more than 3,000 incidents involving lost or stolen substances, according to a study in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. Among those, 84 per cent were classified as “unexplained.”

“It’s quite difficult to track diversion,” said Mark Fan, a researcher at North York General Hospital who studies drug diversion.

In hospital settings, Fan explained, the ordering, dispensing and charting of medication often occurs across multiple different computer systems — and sometimes on paper — that don’t always connect. Linking those transactions can be so tedious that drug losses slip through the cracks, he said.

“Because it’s so time consuming to link these transactions between all these systems, we think there’s a likelihood there could be under-detection happening.”

A 2019 analysis in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, co-authored by Fan, noted controlled opioid losses are increasing in Canada — partly because of the many potential routes for diversion. Doctors might over-prescribe medications or falsify prescriptions, while nurses and other staff might swipe drugs from storage, divert medication meant for the waste bin or substitute doses with something like a saline solution to conceal thefts.

Speaking generally, Fan said diversion can happen in two ways: There’s the physical stream, where someone just takes the drug from storage, and the “more sophisticated” avenue, which involves the manipulation of records and documents.

“Let’s say two boxes of medication arrive at a hospital but (staff) report only one arrived,” Fan explained. “You have more difficulty realizing that something has happened because the documentation almost makes it look like it never showed up.”

Those gaps in tracking align with research Fan co-authored at the University of Toronto, released in 2020, which analyzed Health Canada data from 2012 to 2017 and identified nearly 65,000 reported opioid losses at Canadian health facilities. A large share of those were marked as “unexplained,” a pattern the authors said points to under detection, misclassification of diversion and the difficulty of tracking.

“The prominence of ‘unexplained losses’ in all facilities suggests that further research is needed to understand why Canadian facilities are unable to track the reasons for loss,” the study stated.

“Unexplained losses were something that jumped out at us,” Fan added in an interview. “There’s a lot more we can do to look at our processes in the health-care system in terms of tracking, monitoring and just improving our detection and prevention of these incidents.”

St. Joe’s cases and safeguards

At St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, more than 90 per cent of reported drug-loss incidents between 2020 and 2025 were classified as “missing,” according to The Spec’s data analysis.

Brooke Cowell, the network’s executive vice-president of clinical operations and chief nursing executive, said cases of missing medication can often be attributed to human error like the incorrect counting of a received supply, miscounting of pills, accidental spilling or wasting, and patients declining medication.

“Any controlled substances loss or theft is thoroughly investigated internally,” she said in a statement. “Improvements to our processes are implemented based on the findings of these reviews as per our continuous quality improvement approach.”

Cowell noted that losses or thefts at St. Joe’s are “very rare”: the network securely dispenses more than four million doses of medication per year.

Still, the safe handling and distribution of drugs at its sites is “an extremely important element of (our) operations,” she said.

Every hospital in Canada must take a standardized approach to medication management, but Cowell contended St. Joe’s goes further, with additional safeguards including weekly audits of pharmacy orders and inventory, automated dispensing cabinets that track access, random checks of patient areas to ensure doses match prescriptions and staff training on controlled substance safety.

While St. Joe’s has reported a half-dozen cases of theft since 2020 — three times less than HHS — the volume of drugs stolen in each theft is more than twice as much.

Data shows almost 224 mg of substances were stolen on average at St. Joe’s, while the amount taken per theft at HHS was closer to 78 mg.

St. Joe’s entire theft tally stems from six instances at its Charlton campus in late 2021, all involving an employee who Hamilton police charged with theft under $5,000 and criminal breach of trust in January 2022.

Data shows the stolen lot included 363 doses of hydromorphone, seven vials of morphine, and three tablets of low-strength clonazepam.

According to a decision from the College of Nurses of Ontario, released last December, the employee worked as a registered nurse at the Charlton emergency room from 2015 until August 2021 — just before the thefts — when she was transferred to a non-nursing position as a porter.

The decision stated the worker wasn’t assigned to care for patients or permitted to handle medications when she accessed the hospital’s automated dispensing machine and withdrew hydromorphone 183 times between August and December 2021. The worker used “her own unique access code to override the (dispensing) system,” according to the decision.

St. Joe’s fired the worker in June 2022. Later that year, after pleading guilty to theft under $5,000, the Ontario Court of Justice handed her a suspended sentence of 12 months’ probation. The woman permanently resigned her position with the College of Nurses of Ontario.

The college’s decision noted the former nurse “had a substance abuse condition” at the time of the thefts.

When health-care workers divert drugs

Experts say drug “diversion” — when health-care workers steal or misuse medications — is often linked to substance-use disorder rather than profit.

Sherry Young/Dreamstime

Studies in Canada and the United States suggest health-care workers aren’t immune to the opioid crisis.

A 2019 report from the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists states health professionals who steal drugs from their workplace often do so for personal use and not to sell on the street.

“In most cases, the diverter is suffering from substance-use disorder.”

That’s not to say losses from health-care facilities don’t have the potential to end up being sold.

In the U.S., the Drug Enforcement Administration publishes a report annually on narcotic losses from hospitals and pharmacies. The country saw 6.6 million doses of unaccounted-for controlled opioids end up on the street in 2024, up from five million doses in 2023, according to a recently released National Drug Threat Assessment report. It’s an increase the DEA said might be linked to distrust of fentanyl-laced street-level pills, “creating a renewed demand for licit medications.”

Health Canada, the Canadian authority that captures drug losses from health-care facilities, doesn’t publish an equivalent report.

“We think there could be more work on it, for sure,” Fan said about the state of drug-diversion research and awareness in Canada.

Cases of drug diversion are often investigated as standalone incidents — but it’s the whole health-care system that suffers.

On one hand, it leaves patients at serious risk, from inadequate pain relief because of missing or tampered with drugs to unsafe care delivered by impaired health-care workers. “There’s also potential for infections,” Fan said, pointing to multiple hepatitis C outbreaks in the U.S. that were linked to diversion by health workers using contaminated syringes.

Diversion also undermines public trust in the health-care system — not to mention costs taxpayers. When medications go missing, hospitals have to replace them. There are also a lot of resources that go into diversion investigations.

“You have to interview people, someone has to go through all the records, and that takes time.”

Meanwhile, there’s obvious risk to the diverter of drugs themselves — addiction, overdose and loss of work.

One clear theme in drug-loss prevention research is to focus on the gaps in health systems that allow diversion to happen or go unnoticed — not blame individuals.

After their 2020 study, Fan and his research colleagues at U of T created a free risk assessment tool online that helps hospitals identify vulnerabilities and suggests actionable safeguards. Rather than waiting for losses or thefts to occur, the tool offers a proactive way to detect weak points in medication management systems.

“It’s not just about diversion. It’s also about making sure that we have good controls in place for these medications,” Fan said.

The Institute for Safe Medications Practices Canada, a non-profit dedicated to the advancement of medication safety, thinks similarly.

“Although drug diversion is an intentional act … it is also a symptom of a larger problem,” the institute states on its drug diversion bulletin, adding there should be more emphasis on addressing gaps in health-care systems than on the individual.

“Just as changes have been made to advance medication safety through reporting and learning from medication incidents, a similar strategy is needed to further knowledge about diversion.”