I felt like I was looking at a top secret document. A few days before the Grands Prix Cyclistes de Québec et de Montréal, I sat with Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale directeur sportif Nicolas Guillé in the lobby of the team’s hotel in Quebec City. He showed me a spreadsheet on his phone, just one part of the team’s strategy for the upcoming one-day races in La Belle Province. The name of each of the squad’s seven riders sat in its own cell. Before and after each name, were either the letters “RCR” or “RCR-F,” indicating which model of Van Rysel bike they’d be riding at which race. The partnership between the French team and the bike brand based in the same country started roughly two years ago. To understand the arrangement on Guillé’s spreadsheet, you have to go back to 2019, which is when Van Rysel launched.

Van Rysel has been moving quickly since its inception. Development of its first WorldTour-level road bike began in earnest in 2021. By November 2023, riders on what was then known as AG2R Citroën had models in-hand for the 2024 season. “It was a quite fast process, to be honest with you,” Jérémie Debeuf, Van Rysel’s product manager of race bikes, said to me this past summer. He’s one of the architects behind the speedy development of the RCR. His connection with cycling goes way back. As a kid, he rode BMX, then mountain bike, road, cyclocross and triathlon. More than 20 years ago, Debeuf started working at Decathlon, the large French sporting goods retailer. He believes in that company’s mandate to connect people with sports of all kinds. But when the Van Rysel project started up, Debeuf, the lifelong fan of bikes, was excited. “When the brand was created, it was a dream come true to combine a passion for cycling and passion for business. And, I felt it was something different we could bring to the market.”

Jérémie Debeuf, Van Rysel product manager of race bikes. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

Jérémie Debeuf, Van Rysel product manager of race bikes. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

Like Decathlon, Van Rysel is based in northern France, but the bike brand is what Debeuf describes as a performance ecosystem unto itself. In the City of Lille, Van Rysel (which is Flemish for “from Lille”) has its design teams, engineers, R&D labs, 3D printers, machines for fatigue tests, an area for developing and testing paint, as well as supply management and communication teams. Almost everything is within Van Rysel’s headquarters. The frames are manufactured in Vietnam with the company’s own moulds, and then assembled in France. It all started with roughly 15 people in 2019. Today, the company has approximately 60 employees in Lille and more than 300 worldwide.

Debeuf said the development of Van Rysel’s top road bikes began with some serious number crunching. The company simulated around 25 of the more significant races in the WorldTour calendar, looking at variables such as terrain, riders and even weather conditions. Designers and engineers attempted to make a bike with the right balance of aerodynamics, low weight and frame stiffness that could excel at all the events. Could there even be one bike for all courses? “We clearly saw that to be excellent everywhere, it was impossible to do it with one bike only,” Debeuf said. There’d have to be two. The first would be what Debeuf calls an “aero-light” solution, something that is light enough for steep inclines, but also cuts through the wind efficiently. “It’s a bike that can perform on 70 per cent of the races in the calendar,” he said.

The Van Rysel RCR Pro with its hydro-dipped paint job. This is the bike ridden by the continenal team Van Rysel Roubaix. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

The Van Rysel RCR Pro with its hydro-dipped paint job. This is the bike ridden by the continenal team Van Rysel Roubaix. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

A hydro-dipped Van Rysel RCR Pro. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

A hydro-dipped Van Rysel RCR Pro. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

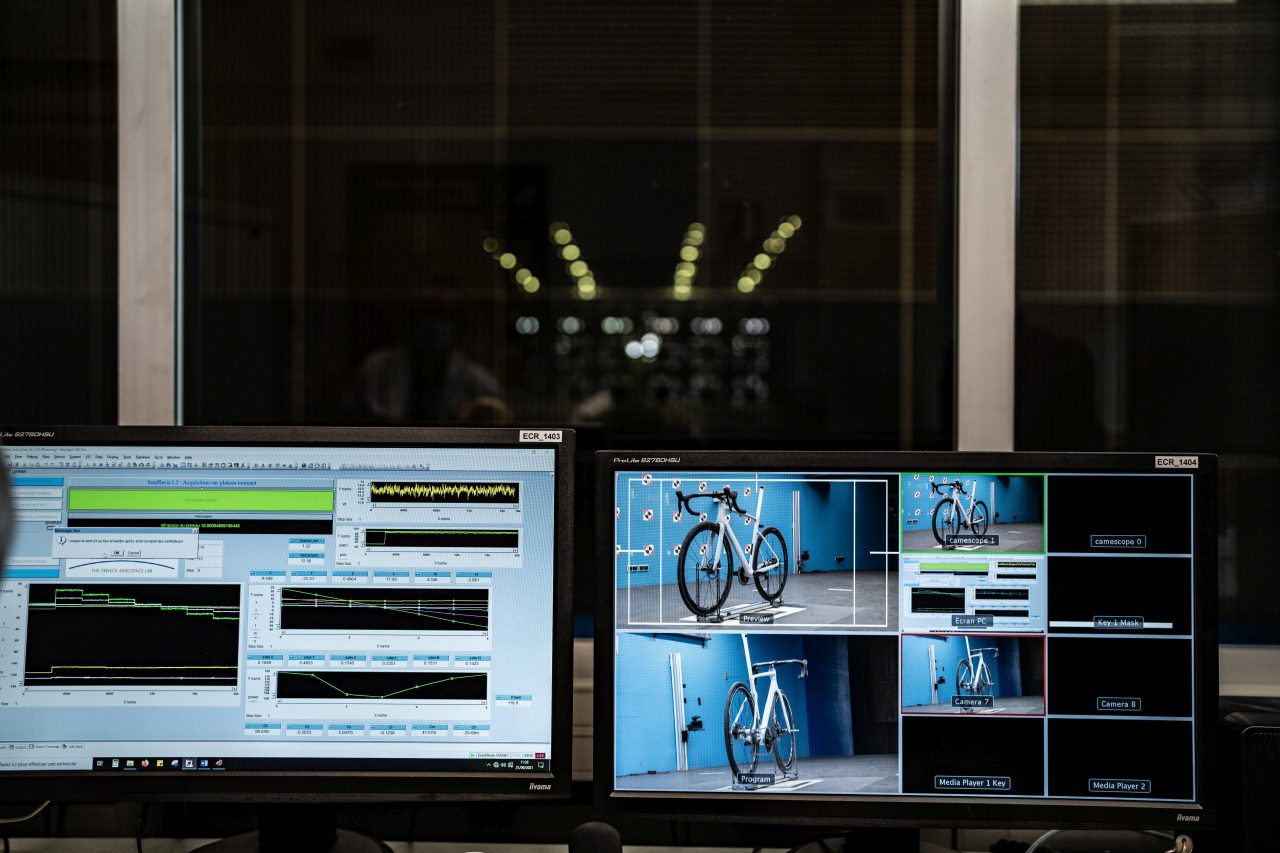

Part of the development process involved a friendly neighbour. “From my office window, I can see ONERA’s wind tunnel,” Debeuf said, referring to the Office National d’Études et de Recherches Aérospatiales nearby. Think of ONERA as France’s NASA. The folks at Van Rysel made contact with some cycling enthusiasts at the aerospace research facility who were keen to help with the development of the new bike. “We have 3D printers here,” Debeuf continued. “We printed different iterations of the frame, fork and bar/stem combo. Then during one week, we just crossed the street to test them in a wind tunnel. So it was quite efficient, finding the RCR’s final shape.”

The bike that the pro riders saw near the end of 2023 was this RCR. (It’s soon to be renamed the RCR-R to differentiate it more clearly from the model that came out soon after.) It featured the mix aero, weight and stiffness qualities that Van Rysel was after. The company says it’s the frame for courses that have more than 1,500 m of elevation gain per 100 km, average speeds of around 35 km/h and climbs with grades greater than 5 per cent. The model that the riders on Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale use is the RCR Pro. Compared with the standard RCR, the Pro is slighter lighter and stiffer, just what WorldTour riders need. For the rest of us, the standard RCR, with its slightly lower price point and frame stiffness, is likely the right frame for our rides.

Wind tunnel testing. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

Wind tunnel testing. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

By May 2024, Van Rysel had the tube shapes settled for its next top-end bike, the aero-focused RCR-F, which was made in collaboration with the aerodynamics experts at Swiss Side. What designers still needed to settle was the bike’s carbon-fibre layup. That month, riders such as Oliver Naesen, Sam Bennett and Dries De Bondt—Classics and sprinter types—tested prototypes to give feedback on the frame’s makeup. The RCR-F then saw racing action at the 2024 Tour de France. For the final validation of the model, we look once again to Quebec City, where rider Paul Lapeira came to the provincial capital with the new aero bike. Van Rysel’s white paper says it saves 1.2 W at the fork, 4.4 W at the head tube and 1.7 W at the down tube at a speed of 45 km/h when compared with the RCR. The one-piece bar/stem combo, a collaboration with Deda, saves 2.7 W. While testers found that the most aero position for a rider is with their hands on the hoods, forearms parallel to the ground and the shoulders pulled in slightly, they added 12 degrees of flare at the drops for sprint stability and for the best possible aerodynamics when charging for the finish.

This past September, shortly after I spoke with team DS Guillé, I met with Lapeira to ask him about what he learned from riding in Quebec City and Montreal in 2024. Lapeira has been involved with Van Rysel for years, giving his feedback to the brand. In fact, the week before he arrived in Quebec, he was in a wind tunnel testing a Van Rysel skinsuit that has a planned release of next year. (“To be honest, the wind tunnel is not that fun because it’s really hard to just stay in a perfect position on the bike for hours. But it’s really some good work in the end,” he said.) What did he discover in 2024 when he had both the RCR and RCR-F in Canada? “RCR-F was better in Quebec because it’s a faster route. Then I used the RCR for the Montreal race,” he said. In 2024, Montreal, considered the harder of the two events, had roughly 1,600 m more elevation compared with the Quebec City circuit. It seemed what Lapeira did in 2024 was also the right formula for 2025, especially since the Quebec City course grew in length by about 15 km and lost about 300 m of elevation gain for this year.

Let’s return back to Guillé’s spreadsheet. While it showed Lapeira riding the RCR-F in Quebec City, other riders on the team would be on the RCR. Guillé explained that bike choice wasn’t simply a matter of the course profile and distance, but also a rider’s abilities and even his role within a race, whether he was a leader or domestique, and even at what point of the race he was expected to perform his duties.

“I think Quebec City really suits me well,” Lapeira said at our meeting. “I would like to play for the win, of course.”

A late move with Tadej Pogačar, Biniam Girmay, Paul Lapeira and Jonas Abrahamsen looked promising, all finished out of the top 10. Lapeira was the best placed in the end in 12th. Image: Grégoire Crevier

A late move with Tadej Pogačar, Biniam Girmay, Paul Lapeira and Jonas Abrahamsen looked promising, all finished out of the top 10. Lapeira was the best placed in the end in 12th. Image: Grégoire Crevier

Two days later, he made good on that plan. In the final lap of the Grand Prix Cycliste de Québec, Lapeira was in the second breakaway group of eight riders that included Tadej Pogačar and Biniam Girmay. They were chasing the group of seven just ahead that featured Julian Alaphilippe, the eventual winner. Lapeira and company came within less than 15 seconds of catching the lead group. It was oh-so-close before the chase collapsed and the peloton mopped up Group 2.

The next day, the teams and organizers all headed west to Montreal. There, I met with Perrine Chudy, Van Rysel’s global communication director. She and her colleagues were setting up the Van Rysel booth in the race’s expo area. (On race day, the place was bumping even before the expo was officially open.) She told me how the links between Van Rysel and Canada were going to go beyond validating and racing top-end bikes on our roads.

Aero testing at one of ONERA’s wind tunnels. ONERA, Office National d’Études et de Recherches Aérospatiales, can be considered France’s NASA. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

Aero testing at one of ONERA’s wind tunnels. ONERA, Office National d’Études et de Recherches Aérospatiales, can be considered France’s NASA. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

In March 2026, there will be a large influx of Van Rysel’s premium products into Canada. Notably, they will be in shops outside of Decathlon stores. Those retailers include six Bicycles Quilicot locations in Quebec, four Bike Depot stores in the Greater Toronto Area, three The Bike Shop spots in Calgary and Steed Cycles in North Vancouver. With the online sales component of some of these shops, Van Rysel expects to have most of the country covered. I asked Chudy why Van Rysel was coming to those dealers as the bike brand has a Decathlon connection available. “We want to be present in Canada and offer a very premium service, a very premium experience,” she said. “We already have Van Rysel shops in Europe and in China. We want to offer exactly the same in Canada. These Canadian shops can offer this kind of service, so it was super important to collaborate with them. They know our bikes and how to fit them.”

Swiss Side worked with Van Rysel on the RCR-F. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

Swiss Side worked with Van Rysel on the RCR-F. Image courtesy of Van Rysel

“And, I have good news,” Chudy added. “Our RCR and RCR-F, the two race models, will be available in December this year.” In March, the time trial bike, the XCR, will land, as will the recently released EDR Ultra all-road bike. It’s what Camille Albisser rode in the most recent NorthCape4000 ultra-endurance event. She clocked 4,000 km in 12 days, crossing eight countries, starting in Italy and finishing in the far north of Norway. Albisser was the first woman to get to the finish. For cyclocross fans, you’ll note that Van Rysel is one of the few companies that make a dedicated CX frame. While it currently has an aluminum and a carbon-fibre gravel bike, two new gravel rigs are on the way. Beyond the bikes, there are helmets and glasses, some of which are tested in the wind tunnel alongside the RCR-F, so a rider can have a complete system of aero products that works as a whole. Van Rysel has shoes, kit and socks. An indoor trainer is on its way, too.

It’s a big push by the company. Chudy said, echoing comments I’d heard from others I spoke with at Van Rysel, that the brand wants to be among the top five names in the world. If you’re asked to list five bike makers, Van Rysel’s aiming to be one of the main ones that comes to mind. The company see Canada as an important market for its global goals.

To click with Canucks, Van Rysel is honing in on something that resonates with those from Lille and those of us sitting atop the 49th parallel: geography. The Van Rysel group—so close to Roubaix, the finish of the Hell of the North—comprises proud northerners, attached to their pavé and cold weather. We, of course, know a little something about the cold, eh? When Van Rysel looks at the Canadian market, it sees a connection it calls, “From North, to North.” I suppose it’s appropriate that its bikes are making their way here in December and March. They’ll be ready to go when the routes are clear. Actually, make that “clear enough for a northerner to ride.”

This story is presented by Van Rysel.