When people hear the word “cancer,” it triggers understandable concern. Communities in northern British Columbia deserve clear information about potential health risks — not confusion. That’s why it’s worth looking closely at recent claims about Chetwynd, fracking, and cancer.

Recently, the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment (CAPE) released a statement suggesting that living near LNG-related infrastructure, including fracking and flaring sites, puts residents at higher risk of certain cancers. One of their spokespeople, Dawson Creek family physician Dr. Ulrike Meyer, said there’s a “growing body of peer-reviewed research” pointing to that risk. CAPE also highlighted data showing that cancer rates in Chetwynd are higher than average – particularly colorectal and female breast cancer.

Put together, the implication seems clear: fracking might be causing cancer in Chetwynd.

But when you look for evidence to support that link, it simply isn’t there.

What’s actually happening near Chetwynd

Chetwynd is not surrounded by active fracking operations. The closest well to the town dates back to the 1950s and has long been inactive. Most were drilled decades ago, long before modern hydraulic fracturing even existed.

That’s an important detail. To suggest that fracking is driving cancer rates in Chetwynd is to overlook basic geography and history: there’s no significant fracking activity in or near the community.

CAPE cites “remarkably higher rates” of some cancers in Chetwynd. But public health experts caution that small communities often show statistical swings that don’t necessarily point to environmental causes.

To establish a credible link between an industrial activity and a disease cluster, scientists need detailed, long-term data on exposures, population movements, and other factors like genetics, diet, and lifestyle. None of that appears in the materials CAPE released.

According to a journal article from the Public Health Agency of Canada entitled “Investigating reports of cancer clusters in Canada”, many suspected cancer clusters don’t lead to definitive causal links being exposed because of limits in data, exposures, and statistical power. Stated authors Catherine E. Slavik, PhD and Niko Yiannakoulias, PhD, “In the overwhelming majority of suspected cancer clusters … the role of chance cannot be ruled out … in very few cases is a link to a specific cause able to be established when they are investigated.”

Raising questions is fine — but evidence still matters

Doctors and advocates have an important role in calling attention to health issues. But good intentions don’t replace rigorous science. When advocacy races ahead of evidence, it risks creating unnecessary fear — especially in small towns already facing enough economic and social pressures.

CAPE’s recent campaign in norther B.C. stated the following: “The BC Centre For Disease Control and published cancer research shows that Chetwynd, a community in the South Peace area, has remarkably higher rates of all cancers, especially colorectal and female breast.”

CAPE’s wording — “remarkably higher rates of all cancers, especially colorectal and female breast” — is designed to shock. But where is the data? The BC Cancer Registry is the gold standard for cancer incidence in the province. Yet it has not published peer-reviewed evidence showing that Chetwynd’s rates exceed provincial averages in a way that’s statistically significant once you adjust for population age, smoking and alcohol use, occupational exposure, and other well-known risk factors. Public community health profiles for Chetwynd do not declare any such “remarkable” spike. The claim is asserted, not proven.

Now here’s what we do know: for nearly six decades, Chetwynd was home to a pulp mill, opened in 1957 and operating until 2015. For generations it sat right in town, the dominant economic engine and a heavy industrial emitter. Anyone from a mill town knows the sulphur fumes, the wastewater challenges, the day-in, day-out exposures that workers and residents alike lived with. As WAC Bennett used to say of the distinctive smell of a pulp mill, “That’s the smell of money.”

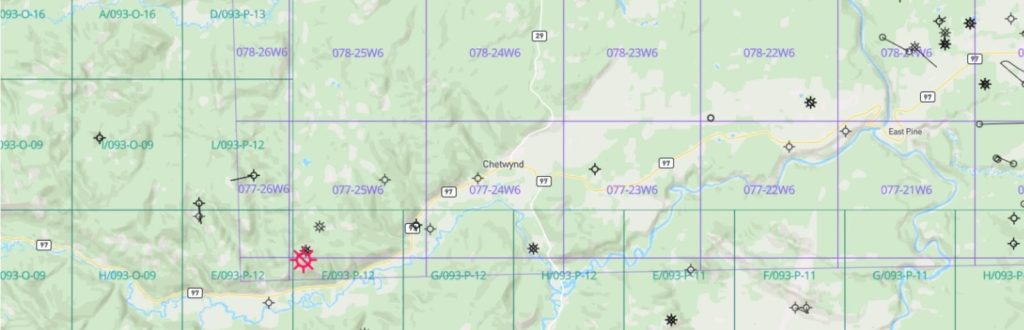

Chetwynd does not sit atop a forest of fracked wells. Pull up maps from StackDX, an interactive oil & gas mapping tool for North America, and you’ll see only a handful of wells in the area — most drilled in the 1950s through 1990s, conventional and long since suspended. The nearest one to town dates back to 1955, decades before hydraulic fracturing was even invented. To suggest that fracking is driving cancer rates in Chetwynd is to build a causal chain out of thin air.

StackDX map for area around Chetwynd BC shows oil & gas development is historically present but not heavy and not close to the populated area. Until 2015, Chetwynd featured a large pulp and paper mill in the centre of town.

A CAPE press conference in Vancouver and Smithers was held to publicize the cancer cluster claims. Speaking as a longtime journalist, I wasn’t too surprised to see it then picked up by multiple outlets, from regional papers to national wires. The CAPE talking points were repeated uncritically, ensuring that thousands of readers and viewers walked away with the unproven assertion that fracking in Chetwynd was causing a cancer crisis.

Chetwynd residents deserve reassurance grounded in facts. At this point, the facts don’t support a connection between fracking and cancer in their community.

Why this conversation matters

Resource development and public health will always intersect, and it’s vital that communities have confidence in both. Responsible operators, local leaders, and health professionals share a common goal: ensuring that development is safe, monitored, and transparent.

If new evidence emerges, it should be tested and discussed openly. But for now, one conclusion stands out — in Chetwynd, the claim that fracking is behind higher cancer rates doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.

As an organization, we at Resource Works are committed to factual, consistent, journalistic standards. If we make a mistake, we fix it. We’re so committed that we share these values wherever possible, and this year for the second year in a row, I’m proud to say we are among the Presenting Sponsors of the Webster Awards for journalism in British Columbia.

And in recent months we’ve been deepening our understanding of responsible natural resources with our new Shaping the Peace report on Northeast B.C., reflecting the real lived experiences of those on the ground in the region.

Our research team spent months examining the safety and environmental record in the region in question, asking tough questions and weighing the facts. We also studied the benefits of NEBC activities – to residents and rights holders in the region as well across the province.

Here’s the report link: Shaping the Peace — Balancing Energy, Environment, and Reconciliation in Northeast BC’s Peace River Region

What we found was that while risks are real, and the cumulative impacts of past industrial practice are real and require remedies, the most remarkable thing is what’s going on today: the emergence of a new restoration economy that is creating win-wins, including for First Nations rights holders, all the while accompanying a modern, ever-improving and enormously beneficial energy and resources economy.

Nobody is dismissing health concerns. But accuracy also matters. If we care about northern communities, we must separate evidence from ideology. CAPE failed that test here. Chetwynd deserves better than to be used as a prop in someone else’s political campaign.

When executed with tight performance conditions and transparent accounting, Canada’s LNG is a nation‑building investment in human health. Steady jobs mean pride in work, children lifted out of poverty, women in the workforce, apprenticeships, Indigenous equity, exports and system reliability — while meeting credible climate standards.

To the physicians at CAPE: I get it. You’ve chosen to speak up because you see patients and communities that you care about, and you want them to be safe. That’s the right instinct.

Where we might differ is not in our concern for people’s health, but in how we get from concern to conclusion. In a place like northern B.C., where resource work and family life are woven together, it’s easy for fear to travel faster than facts. When that happens, trust can fray — and that’s not good for anyone.

My hope is that we can meet somewhere between the clinic and the compressor station — where data and lived experience sit at the same table. Let’s make sure the next conversation is one we have together, not across a microphone.

📖 See our deep-dive report: Shaping the Peace