This schools-based study in Nepal was the Global Campaign’s first in SEAR. We found that the vast majority of children and adolescents experienced headache in the preceding year: an estimated 83.9% corrected for age and gender, very similar to our earlier finding of 84.9% among adults in Nepal [8]). Migraine was the most common headache type. An estimated 2.2% had headache on ≥ 15 days/month, but only 0.3% in association with acute medication overuse (pMOH). Estimated 1-day prevalence was 19.9%.

The study highlighted the diagnostic difficulties commonly encountered in epidemiological studies among young people [3, 4, 8]. In large cross-sectional studies, headache diagnoses can be based only on subjective reporting of symptoms elicited by questionnaire. How questions are asked, and understood through the barriers of young age and linguistic and cultural diversities, are therefore pivotal. In previous papers [3,4,5,6,7,8] we have referred to children’s potential susceptibility to suggestion (built into leading questions), their tendency to favour affirmative responses, and their likely beliefs, reinforced in a school setting, that there are “right” and “wrong” answers. The diagnostic question set used in HARDSHIP, applying ICHD-3 criteria with regard to headache features and associated symptoms (criteria B-D), has not been formally validated: in these age groups, this is very difficult to do, requiring double interrogation with no benefit to the participant. It has, however, been used previously in nine languages and six countries [3,4,5,6,7,8], always translated in accordance with the Global Campaign’s translation protocol [16], with subsequent assessment of comprehensibility in a sample of the population of interest. In addition, in these previous studies, self-completion of questionnaires has been mediated, as it was here, by the class teacher or investigator to assist comprehension when needed. These measures have not entirely obviated diagnostic uncertainties. In particular, in countries in sub-Saharan Africa, very high proportions reporting symptoms usually associated with migraine have led to unfeasibly high estimates of migraine prevalence (definite + probable) [3, 4, 8]. Furthermore, specifically in Nepal, our previous study among adults encountered almost universal reporting of photophobia by those with headache, so that this symptom had no value in differential diagnosis [9]. In the present study, almost 95% of those with headache reported phonophobia (94.6%), and an unlikely proportion reported vomiting (43.0%). Also troublesome was that the conventional diagnostic criteria for UdH (mild headache lasting < 1 h) did not behave as in most previous studies [4,5,6,7,8], capturing only 4.8% of participants because very few reported mild headache (7.8%).

Our solution here was to modify the criteria for UdH, to include moderate headache but retaining the essential criterion of short duration (< 1 h). In justification, distinction between mild and moderate headache (the actual terms used were “not bad” [in Nepali: garho hudaina] and “quite bad” [madhyam garho]) is obviously highly subjective at any age, and diagnostic distinction ought not to turn upon this. The result of this modification was prevalence estimates for UdH of 31.7% (up from 4.8%) and for migraine of 39.8% (still high, but down from a very improbable 58.4%).

The observed 1-year prevalence of any headache (85.4%) falls near the higher end of the range (61.3–88.5%) found in other schools-based studies in this series conducted by the Global Campaign [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Higher prevalence among females than males, and among adolescents than children, are universal in these studies [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Both in Benin [3] and Zambia [8], estimates of migraine prevalence were implausibly high (53.2% and 53.4% respectively), with diagnosis driven by high proportions reporting nausea and/or vomiting [8] or photophobia and phonophobia [3]. In both countries, substantial proportions of those classified as probable migraine reported usual headache durations of < 1 h [3, 8]. In these studies, modification of the criteria for UdH to include moderate headache would markedly reduce the estimates of migraine prevalence, bringing them into the plausible range. We suggest this supports this modification.

With the modified criteria applied, observed prevalence of headache overall was higher among adolescents than among children (77.3% vs. 91.8% [Table 4]), as were estimates for migraine, TTH, UdH and other H15+, although increases in migraine and UdH did not quite reach significance after adjustment (Table 6). As a proportion of all headache, UdH declined very slightly among adolescents. However, these differences were small: headache is highly prevalent even among children in Nepal, at levels comparable to those among adults [9].

On this last point, the present study is nicely complementary to our previous study in adults [9, 10], informing health (and educational) policy in Nepal that headache affects the great majority of those aged 6–17 years as well as the great majority of adults aged 18–65. There are differences, of course: principally in the occurrence in children and adolescents of UdH (believed to be headache in the developing brain yet to manifest as migraine or TTH [6]), but there is also a strikingly lower prevalence of H15 + among children and adolescents (2.2% vs. 7.4% among adults). MOH is known to take time to develop [20]. Other H15 + was likely to have included chronic migraine and chronic TTH, which evolve from their episodic precursors, again over time [21, 22]. This highlights the theoretical opportunity for preventative intervention in childhood and adolescence to avert much lost health in adulthood – an attractive postulate, but unfortunately it remains unsupported by empirical evidence.

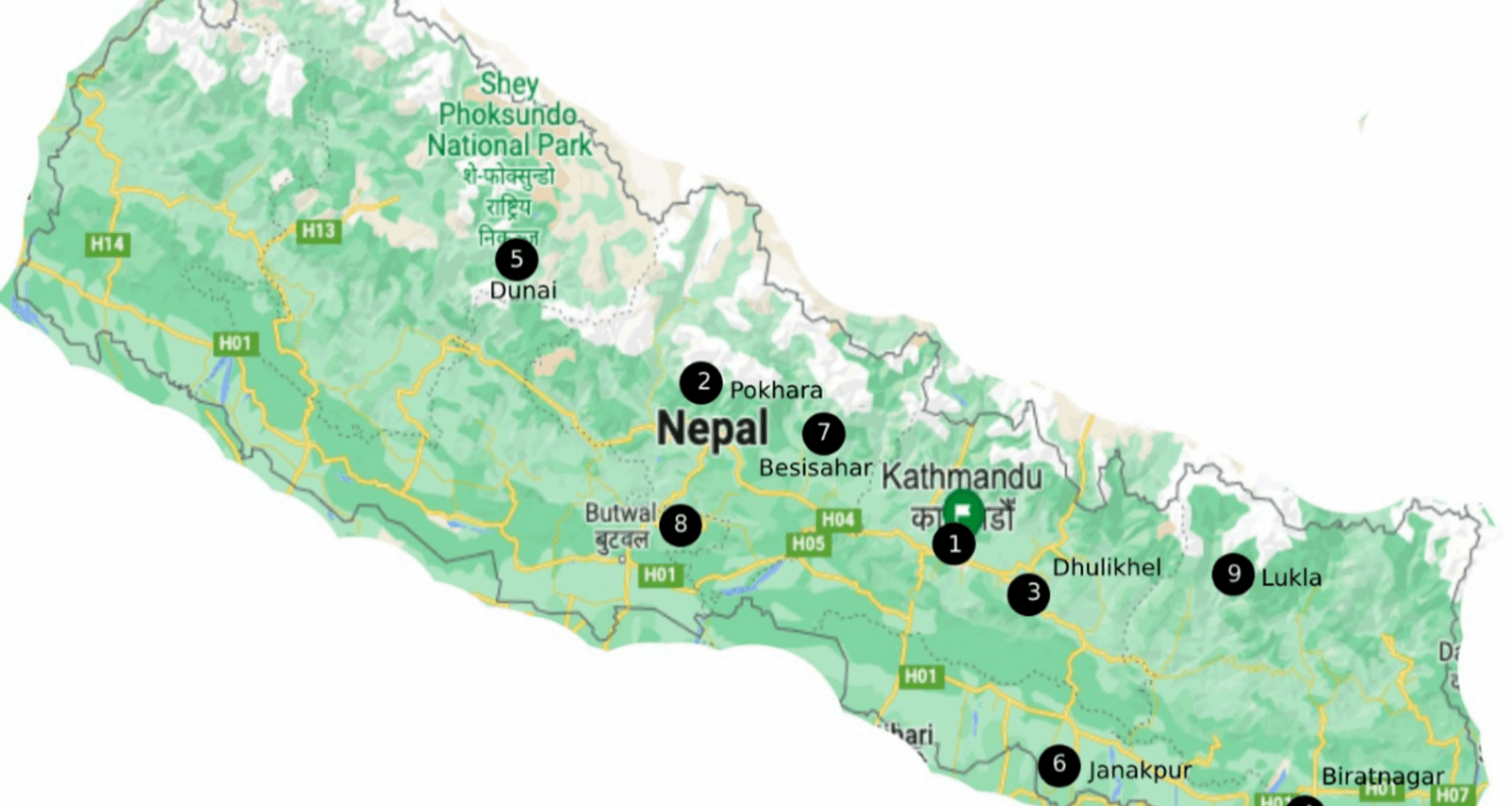

An important concordance between the present results and those of our adult study in Nepal is the positive association between migraine and altitude, appearing in both studies to weaken above 2,000 m [23]. In a recent similar adult study in Peru, we found a more robust association [24]. This, therefore, is the third time we have been able to demonstrate this relationship, and, to our knowledge, the first time it has been demonstrated in children and adolescents. The cause remains unclear [23]. Our finding here that UdH was negatively associated with altitude, in a manner that was the inverse of that of migraine, is thought-provoking: what would manifest as UdH at low altitude perhaps acquires the attributes of migraine at high altitude.

Finally, we note that the 20.7% of the sample reporting HY (24.3% of those reporting any headache in the preceding year) were a clearly higher proportion than predicted from reported headache frequency, which was based on recall, with 1-week recall (17.6%) giving a closer match than 4-week recall (10.3%). This pattern was repeated across genders and ages for all the episodic headaches (Table 7). On this evidence, children and adolescents underreport headache frequency – as we have seen in previous schools-based studies [3,4,5,6,7,8]. In fact, this tendency has been a robust finding across geography, culture and age, since it has been reported in adult studies also [24,25,26,27] – though to a lesser degree, perhaps because adults have a better sense of time.

Because, in Global Campaign methodology, UdH takes diagnostic precedence over migraine and TTH [7], prevalence estimates from studies using this methodology cannot sensibly be compared with those that have not taken account of UdH. Many published studies of children and adolescents have found large proportions of unclassified headache that might have been UdH but were not identified as such (for discussion of this, see [7]).

The strengths of this study were in the use of standardised methodology, albeit with modifications to the questionnaire [14, 15], coupled with an adequate sample size derived from almost nationwide sampling. As noted in Methods, we could not sample in Province 7. Most characteristics of Province 7 (cultural, geographic and economic) are a mixture of those of Provinces 5 and 6, all remote and relatively underdeveloped. These three provinces have similar literacy levels, life expectancies, ethnic diversity, traditional lifestyle and religious practices [28, 29]. The principal limitations were those inherent in cross-sectional surveys, and in the uncertain reliability of information gathered from children. The additional uncertainties in recall over the past 4 weeks were countered by separate enquiry into HY. Already discussed in length are the diagnostic issues, and our modification of the standard HARDSHIP algorithm with regard to UdH. There may be an underlying limitation in the ICHD criteria themselves in that they do not apply well to children, particularly with regard to duration [30]. We believe this underpins the importance of including UdH as a separate diagnosis, rather than stretching the criteria for migraine as has been suggested [30], although it is not yet clearly established how UdH should be defined.