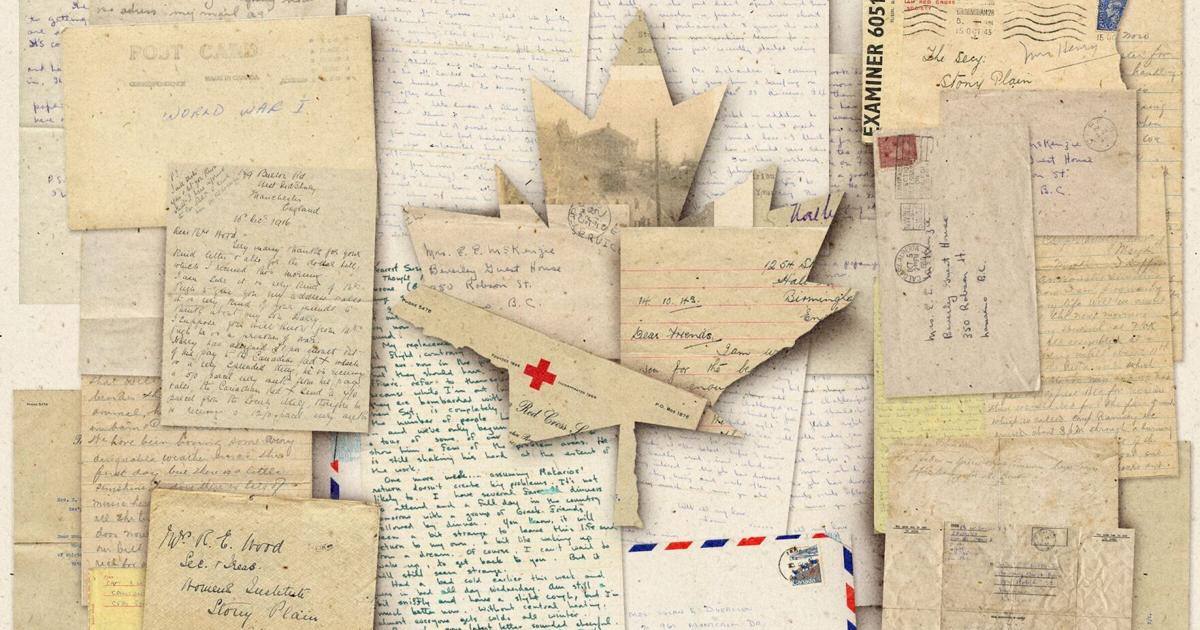

A letter from five Alberta women that legally redefined who a “person” is. A correspondence that created the century-old iron ring tradition bringing in engineering standards. Before social media campaigns, these pivotal moments in Canadian history started with a piece of paper, a pen and a goal.

But the glory days of letter-writing have passed. Canada Post now delivers an average of two billion letters a year — down from 5.5 billion 20 years ago, marking a sharp decline in letter door deliveries (even if most are not personal letters). And the postal service is in talks to end home mail delivery. Canadian postal workers moved from a nationwide walkout to a rotating strike on Oct. 9, protesting the federal government’s decision to restructure the Crown corporation while mail delivery resumes.

Under the Liberal plan, four million households across Canada would transition to community mailboxes in the next nine years, and 53,000 workers could lose their jobs.

For historians and archivists, the looming death of the letter means a crucial way of documenting history and past struggles will be lost forever — and in a way that isn’t easily replaced by social media.

“It feels like something is changing that’s very monumental to so many generations,” said Cheryl Thompson, an author and archivist. Letter-writing “was the only way people thought that they could see change.”

Stephen Davies, director of the Canadian Letters and Images project, dedicated to digitizing personal materials from Canadian war veterans, said these records were important for documenting stories that would have otherwise been lost and create an “accessibility to the past.”

“They’re absolutely pivotal in understanding who we are as Canadians,” he said. “Every letter is important. Every letter is a fragment of our past and once it’s lost or destroyed, that’s gone forever.

“These are the stories of unique Canadians.”

Future historians will have a “very difficult time” putting together the lives of Canadians as forms of communication shift online and onto social media, Davies said. “We’re going to lose the written communication (that) is vital to the record of a country.”

The Star takes a look back at some famous letters in Canadian history and the change that followed.

The Persons Case letter

By the 1920s, most Canadian women had already won the right to vote in federal and most provincial elections. Yet because they were not legally considered persons under provisions of the British North America Act, they were still barred from holding public office or having legal status within their marriage.

In 1927, a group of five Alberta women — Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Louise McKinney, Irene Parlby and Nellie McClung — penned a letter to the Supreme Court of Canada, protesting the exclusion of women from the Senate and other elected federal positions.

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that women were not considered “persons” under the BNA Act and therefore could not be appointed to the Senate.

Ronald Stagg, professor emeritus at Toronto Metropolitan University, said the letter and petition was a way to challenge the “lack of political clout” for women at the time. “They couldn’t even own property, except under very specific conditions.”

The decision was later overturned by Canada’s highest court of appeal at the time, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, in 1929. While it would take decades for some groups, including Indigenous and Asian women, to gain the same rights, it marked a major step for gender equity.

“The five women who took this up were among the group who believed that having the vote was the way to get other reforms,” Stagg said. “It didn’t just open up the Senate to women, it opened up a whole range of roles for women.”

The iron ring correspondence

The story of the iron ring ceremony began with the Quebec Bridge collapse in 1907 which claimed the lives of 76 workers. Some had been crushed by twisted steel, while others fell to their death or drowned before rescue boats could reach them. The deaths were blamed on defective design and neglect.

Nine years later, the bridge would collapse again, claiming 13 more workers’ lives.

In an effort to prevent future tragedies, Canadian professor Herbert Haultain began envisioning a ceremony for engineers, where they would commit to high ethical standards and responsibility.

So in 1923, Haultain corresponded with British novelist Rudyard Kipling, who referenced engineers and their work in his writings, and thus The Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer was born. It would work as a guide for young engineers to understand the “consciousness” of their profession.

Kipling would create the text of the ceremony that would be uniquely Canadian and proposed the iron ring’s design, according to University of Toronto archives. Their correspondence through letter-writing would lead to a century-old tradition still practised by engineering schools in Canada and the U.S.

One of the original iron rings forged for the Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer, which can be found in University of Toronto archives. The ceremony was born out of correspondence between Canadian professor Herbert Haultain and writer Rudyard Kipling.

Dan Levert

Viola Desmond’s pardon

Viola Desmond was arrested and dragged out of a movie theatre in New Glasgow, N.S., in 1946 for refusing to leave a “whites-only” section because she was a Black woman. She spent a night in jail and was released after paying a $20 fine and court costs. Desmond lost her appeal, but her case led to the abolishment of segregation laws in the province in 1954.

Desmond’s youngest sister, Wanda Robson, led the fight to have her exonerated. Robson fought to preserve Desmond’s legacy by raising awareness about the arrest.

In 2009 — more than six decades after the arrest — Robson wrote a letter to the mayor of New Glasgow and requested revoking the conviction of her sister.

Desmond received a posthumous free pardon in 2010 by then-premier Darrell Dexter.

“What happened to my sister is part of our history, and needs to remain intact,” Robson said in a news release at the time. “We must learn from our history so we do not repeat it.”

In 2018, Desmond was selected to appear on the new ten-dollar bill and was the first non-royal woman to be featured on Canadian currency.

“It was the first realization of … a de facto Jim Crow segregation,” Thompson said. “It got amplified for so many people, they did not know that segregated practices were still happening in Canada.”

Wanda Robson, sister of Viola Desmond, holds the new $10 banknote featuring Desmond in Halifax on March 8, 2018.

Darren Calabrese/The Canadian Press file photo

In Flanders Fields

Canadian officer John McCrae would often write home about daily struggles and life in the trenches and on the front lines. With a close friend, Alexis Helmer, he served alongside 18,000 soldiers in Ypres, Belgium, where the heaviest battles would take place.

In one letter to his mother in 1915, McCrae writes about Helmer’s death and burial service. Wild poppies were scattered around Helmer’s makeshift grave, set with a simple wooden cross.

On the same day, McCrae would write “In Flanders Fields,” his friend’s death part of the inspiration. In a separate letter to magazines, he mailed it off. While it was initially rejected, it began circulating in magazines months later — without McCrae’s name — and would help with recruitment and fundraising efforts throughout the war.

It would be McCrae’s second-last poem. He died of pneumonia in January 1918.

His poem would lead to the poppy becoming an international symbol of remembrance and would be recited by millions of Canadians every year on Remembrance Day.

The Japanese Canadian Redress Letter

During the Second World War, nearly 21,000 Japanese Canadians were ripped from their homes and sent to internment camps, soon after the Pearl Harbour attacks in the U.S. in 1941.

The federal government confiscated and sold their property and used the War Measures Act to remove Japanese Canadians from the Pacific Coast for “national security reasons” — even though senior military and RCMP officers said they posed no threat.

After the war ended in 1945, they were offered a choice to resettle in Eastern Canada or be deported to Japan. They would be allowed to return to the West and receive their full citizenship rights four years later.

In a years-long campaign for redress, Art Miki, president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC), wrote several letters to prime minister Brian Mulroney, according to the NAJC.

And nearly 40 years later, in September 1988, Japanese Canadians would receive an apology and compensation for their losses from the Mulroney government.

The discovery of insulin

After briefly considering becoming a Christian minister, switching to medicine and serving in the First World War, Dr. Frederick Banting got an idea for how to potentially cure diabetes. A doctor with his own practice in London, Ont., he was encouraged to reach out for support at the University of Toronto for his proposed research.

The university hosted large research facilities under the direction of Dr. J.J. Macleod, who was skeptical since other researchers had similar ideas and more experience than Banting.

Yet, Macleod wrote a letter to Banting, granting him permission to use his lab and resources, seeing no harm in allowing the scientist to try. The letter outlined the best time for Banting to start his research in May 1921.

After achieving positive results and expanding their experiments, Macleod, Banting and his assistant, Charles Best, would conclude their research with the discovery of insulin, which helps manage diabetes — and go on to win the 1923 Nobel Prize.

Blueprint for a country

The correspondence belonged to John A. Macdonald, who frequently wrote to figures such as George-Étienne Cartier and George Brown. They would talk about what military defence would look like, determine national boundaries and how government affairs should be run. Maps detailed railway construction to link the east and west coasts.

While the majority of the records in Library and Archives Canada are post-Confederation, there is an “extensive correspondence” about the country’s founding and events leading up to it. On July 1, 1867, Canada was born after the terms of Confederation were agreed on, following a “series of conferences and orderly negotiations.”

These letters and documents offer insight into the challenges and ideas that continue to shape Canada today.