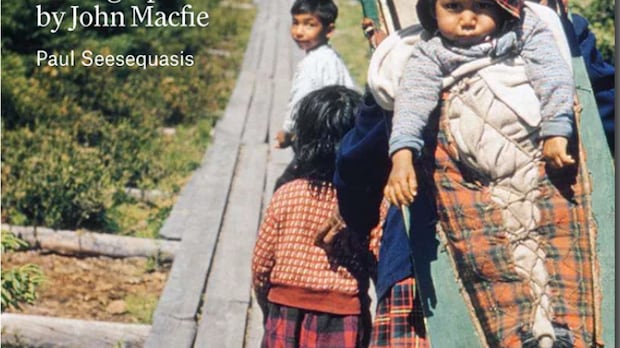

In the 1950s and ‘60s a trapline manager named John Macfie spent time travelling throughout the Hudson Bay watershed.

His work took him to Sandy Lake, Fort Severn and many other communities where traplines were flourishing.

He took his camera with him, and in doing so captured the daily lives of the Anishinaabe, Cree and Oji Cree people he met along the way.

Those images have been brought together in a book called People of the Watershed.

An exhibit of those images is now on at the Lake of the Woods Museum in Kenora, Ont. until Dec. 21.

The curator behind the exhibit and the author of the book, Paul Seesequaisis, is Willow Cree from Saskatchewan.

Paul Seesequaisis is Willow Cree from Saskatchewan. (Submitted by Paul Seesequaisis)

Paul Seesequaisis is Willow Cree from Saskatchewan. (Submitted by Paul Seesequaisis)

Seesequaisis spoke with Mary-Jean Cormier, the host of Superior Morning, about the book and how he’s been working for years on reclaiming photographs of Indigenous people.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mary-Jean Cormier: When did you discover the photos of John Macfie?

Paul Seesequaisis: It was around the pandemic time. I was doing some research and I came across these photos in the Archives of Ontario and they really intrigued me because firstly, they covered such a vast territory and they’re from a particular period of time as in the Hudson’s Bay watershed.

LISTEN | Paul Seesequasis speaks with Mary-Jean Cormier:

Superior Morning9:39Paul Seesequaisis: People Of The Watershed

A new exhibit at Lake of the Woods Museum offers a window into the daily lives of Anishinaabe, Cree and Oji Cree people in northern Ontario in the 50s and 60s. We talk with the curator about the compelling images, and the amateur photographer who captured them.

So, I began to wonder who was this person? And eventually I tracked down John Macfie. He was still alive. He was on Facebook and I messaged him and that’s how we connected.

MC: And who is John Macfie?

PS: He was quite a remarkable man. When I met him on Facebook he would be already in his early 90s, but still sharp. His mind was still sharp as tacks. He worked as a trapline manager through the whole Hudson’s Bay watershed from the early 1950s through to his retirement from the ministry, which would have been in early 1960s, which was interesting in itself because he travelled to all these communities by float plane, by canoe, by dog team in the winter, etcetera. We’re talking pre-snowmobile times.

But he also was very much an amateur photographer. And that’s kind of the legacy or gift John Macfie, in this particular project, left us. He also was a community journalist in Perry Sound, very well known as a local writer and commentator and very much a man of the people. He was one of those kinds of journalists who I guess you would call a working journalist and photographer. And his gift of photography, I think captured a very important period of time.

MC: Do you know why he was so interested in photography and in taking pictures of the people he was encountering?

PS: I know a little bit of his family history. His mother had been a photographer and he was given a camera himself. So, he always had an interest in it and he also was very much interested in people and writing about people. And that’s how he became a journalist as well. But when he got the job as a trapline manager, it afforded him an opportunity few people at the time had, which was to travel this vast expanse of northern Ontario, which was not easy or cheap at the time.

People of the Watershed (JohnMacfie/Archives of Ontario)

People of the Watershed (JohnMacfie/Archives of Ontario)

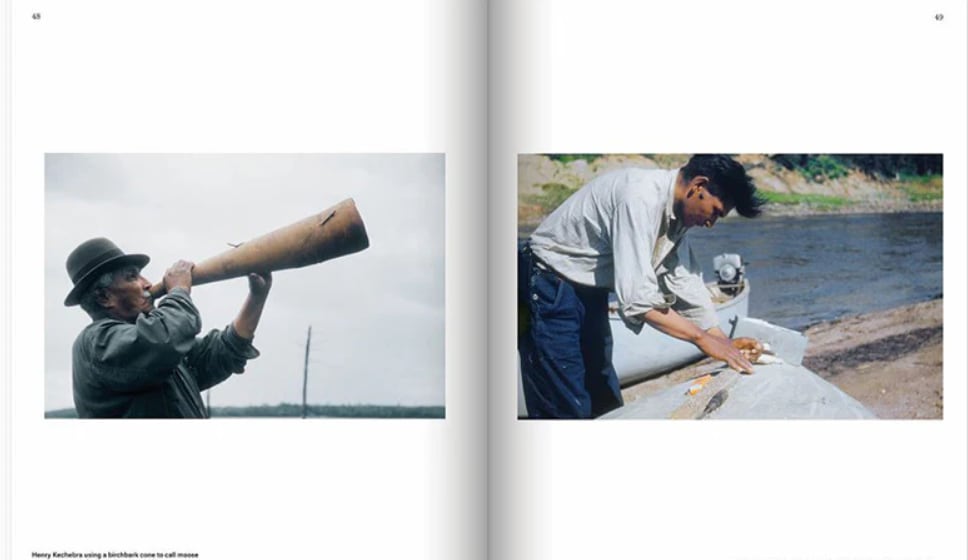

So, he had this opportunity and he had this camera and he just began to take these photos, both in colour — these beautiful colour slides — and also in black and white. I focused on the colour for [People of the Watershed] because the colours were so vibrant. They weren’t retouched and they just capture a period of time and a lifestyle that is no longer there of course, when people very much lived off the land, almost semi-nomadic and the fur trade was still a viable economic option.

So, it was that period of time of transition and he just happened to be placed there at that time and I think that just made his photography all that more impactful.

MC: Do you have any particular images that really jumped out at you or were favourites?

PS: There’s so many. Some of my favourites are the Tikinagans, which are to carry babies — carved out wood with a moss bag with them. And in my travels recently and talking about John Macfie, so many communities are trying to revive that, and maybe the last person who knew how to make them had passed 20 years ago, and now they’re trying to revive it.

So, that connection, those simple day-to-day things that people are trying to revive are something that really has made an impact for me from these photos to realize that these are actually not just aesthetically pleasing images, but they have things in there that people are trying to regain. So, that was really one thing that’s stuck out thematically across the exhibition.

The other one that would be a favourite was a woman called Maria Mikenak and she was a woman who lived out in the bush, and she only came into town a couple times a year and she’s very self-sufficient.

Macfie heard about her, this is his journalistic side, he was curious enough that he hung around for a couple of days waiting for her to come in because he knew from the community that she would be coming in for one of her rare visits to town. So he waited, waited. Finally she showed up and he took a series of photos of her with her nephew in a birchbark canoe that she made herself.

So, that kind of impacts me because he made a record of her and she might be a woman who, other than a few people, would be totally forgotten today. But his photos leave as photography does, at least the legacy of her and her story, which is a very interesting story. So that one I think would be a personal favourite of mine.

MC: Non-Indigenous photographers are sometimes seen as having a gaze or an anthropological approach to taking photographs of Indigenous people. How would you describe that relationship here in terms of photographer to subject?

PS: I think that’s true of not just Indigenous, non-Indigenous photography. It’s true across all photography. There’s always this extractive side of the photo. Do you have permission? Do they know you’re taking the photo? Are you framing something that’s contentious or tragic? All those issues come up with photography.

I think what makes John Macfie kind of transcend that distance — one was probably his personality. He’s a very engaging person. Also, his talent as a photographer and that people knew him. So, the more people saw and the more at ease they were, so you don’t get the sense of him kind of sneaking or extracting photos to capture ethnographic material, but more or less someone who’s known in the community and is trusted. And I think that kind of rapport he had gives his photography an intimacy that you don’t see in all photography. He really had a connection and, to me, that makes his images much more powerful.

MC: I understand that in some of your previous work, you’ve heard from people who have identified people in the photographs. Have you heard from anyone in the course of publishing this book?

PS: I have. There have been a few messages coming in, people who say ‘that’s my grandfather, that’s my uncle.’ So these things have all come up because of people seeing the exhibition. There’s been a number of that happening and I imagine there’s going to be more as the exhibition goes on.