For nearly five decades researchers were stumped by the species of a fossil unearthed near the TTC’s Islington Station, but now they have a better idea of the genealogy of what became known as the Toronto subway deer.

In 1976, a construction worker uncovered the fossil and contacted the Royal Ontario Museum to have a look at it, bringing about a mystery that would ultimately take decades to solve.

This specimen, comprised of a partial cranium with incomplete antler beams, dates back 11,300 years, just after the Pleistocene era (also known as the Ice Age) had ended. It is the only specimen of its kind to be found.

“It was different enough from anything else that was known at the time,” Burton Lim, assistant curator of mammals at the ROM told CTV News Toronto. “It was described not only as a new species of science, but also in a separate genus that was new.”

The Torontoceros hypogaeus, the “horned Toronto deer from underground,” had unique antlers, which were thick, heavy, nearly horizontal and protruded in an asymmetrical way not seen in any modern-day deer species.

Because of that, researchers thought that it was more closely related to the caribou.

Torontoceros hypogaeus A sketch of the Torontoceros hypogaeus, the Toronto subway deer. (Trent University/Sherri Owen)

Torontoceros hypogaeus A sketch of the Torontoceros hypogaeus, the Toronto subway deer. (Trent University/Sherri Owen)

“When you look at caribou, or photographs of caribou, they’re the only deer really that has a part of the antler that goes down across its nose,” Lim said. “Other deer don’t have that, their antlers sort of spread out, sort of above their head.”

Aaron Shafer, associate professor at Trent University, and graduate student Camille Kessler, kicked off the collaborative study with the ROM, as they wanted to understand the genetic diversity of the deer family, comprising of elk, caribou, moose, whitetail and mule deer.

“One way you can study diversity over time is through what’s now become known as ancient DNA,” Shafer told CTV News Toronto. “In the past decade, techniques have allowed us to be able to get DNA and analyze it from really old specimens—we’re talking thousands to tens of thousands (of years).”

For the Torontoceros, they tested a piece of bone fragment from the back of the antler. While the thousands-year-old sample showed signs of damage consistent with ancient DNA, they were able to identify the specimen as a male, and that it was a sister species to whitetail and mule deer rather than the caribou, invalidating previous theories and studies.

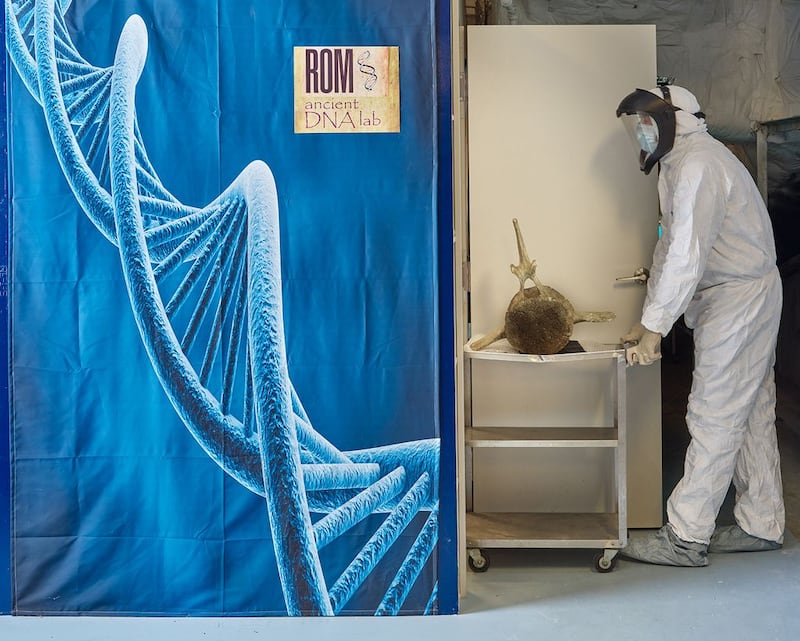

Ancient DNA lab At the Royal Ontario Museum’s ancient DNA lab. (ROM/Oliver Haddrath)

Ancient DNA lab At the Royal Ontario Museum’s ancient DNA lab. (ROM/Oliver Haddrath)

“I learned to temper my expectations, and I don’t get super excited with results because we’re always reanalyzing things, but that was a cool finding,” Shafer said. “This isn’t what the most recent experts say it is … the plot thickens, so to speak.”

The study notes that the Torontoceros was a “phenotypically and genetically unique lineage,” either belonging to Odocoileus (genus of medium-sized deer) as a separate extinct species or as part of an extinct lineage that diverged from mule deer.

Shafer also noted that this fossil is more than 11,000 years old, meaning this species—which would have roamed the Great Lakes with mammoths and mastodons—likely went extinct around the time of the Ice Age. North America saw between 33 and 37 large mammal genera go extinct following the Ice Age, the study notes.

“We know there were actually other deer species, the mountain deer, for example, closely related to white-tailed deer and mule deer, that went extinct, so put in that context, it’s not necessarily surprising,” Shafer said.

“I think if you were to look at more and more fossils, especially with the new tools we have, it’s likely that there are other representatives of Torontoceros that exist in museums, or other deer species, other large mammals, that have gone extinct that we’re now discovering through ancient DNA analysis.”

The Toronto subway deer’s fossil will be back on view in the fossil mammal gallery at the Royal Ontario Museum on Dec. 6.