William Mills – Bill to his friends – was 25 when he rocked up in Paris in 1932 with an ambitious goal. He wanted to become the first Briton to take part in the Tour de France. A star of the Southern Region’s Brighton Stanley Wanderers, Mills was a record-holder over 50, 100 and 150 miles. Against the clock, he had nothing left to prove. Now he wanted to go wheel-to-wheel with the best riders on the Continent, and knew that competing in the Tour would test his abilities to the limit.

French newspaper L’Auto introduced him as “one of the best English amateur road racers”, adding that his domestic palmarès included “many second places behind Southall.” It was not faint praise; Frank Southall was so dominant on the UK scene that finishing second to him was practically winning. For L’Auto, having a Brit in the Tour was an exciting prospect: “[Having] an English rider in the grande épreuve would be a new attraction,” the paper enthused, recalling British successes of the 1890s, before speculating: “Thirty years on, will we again see the famous matches of yesteryear between our road riders and the English?”

Since the 1890s, few British riders had taken on the challenge of Continental road racing. On the track, Britain could hold its head high, with stars such as Tommy Hall and Sid Cozens winning in the Vel d’Hiv and the Parc des Princes, the Buffalo and the Cipale. But on the road, it was slim pickings. Freddie Grubb had given it his all in 1914, even making it as far as the Giro d’Italia. But the standard of racing in France and Italy was a world away from that in Britain. Being one of the UK’s best riders didn’t guarantee Mills would hold his own against riders from France, Belgium and Italy.

You may like

Mills’s reputation was sufficient to earn him a ride with the team of Swiss champion and three-time Hour record holder Oscar Egg. There was no time for Mills to get settled into professional road racing: he was thrown in at the deep end, with his first race for the team being Paris-Roubaix in March 1932. After the recon, he told L’Auto: “The cobblestones were very bad and racing in a peloton scares me. At home in England, we never race like this, always against the clock.”

The landmark appearance of an Englishman in the race was highlighted in a race report in Le Miroir des Sports: “For the first time in almost twenty years, there was an English rider, C.W. Mills, [sic] secretary and crack of a Brighton cycling club, who had turned professional for the occasion.” Although his effort was courageous, it ultimately fell short. “He held on quite well until Breteuil, but alas! then disappeared from the fray, which suggests that he still needs a few kilometres of training.”

After his Roubaix DNF, Mills’s next outing in an Oscar Egg jersey was in April 1932, at Paris-Tours, a race Egg himself had won. Mills again struggled to stay afloat, notching up another DNF. In its post-race analysis, L’Auto was scathing, branding Mills a one-trick time-triallist “who will never be worth anything in road races”. After just two races, Mills’s dream of becoming the first Briton to ride the Tour de France was over.

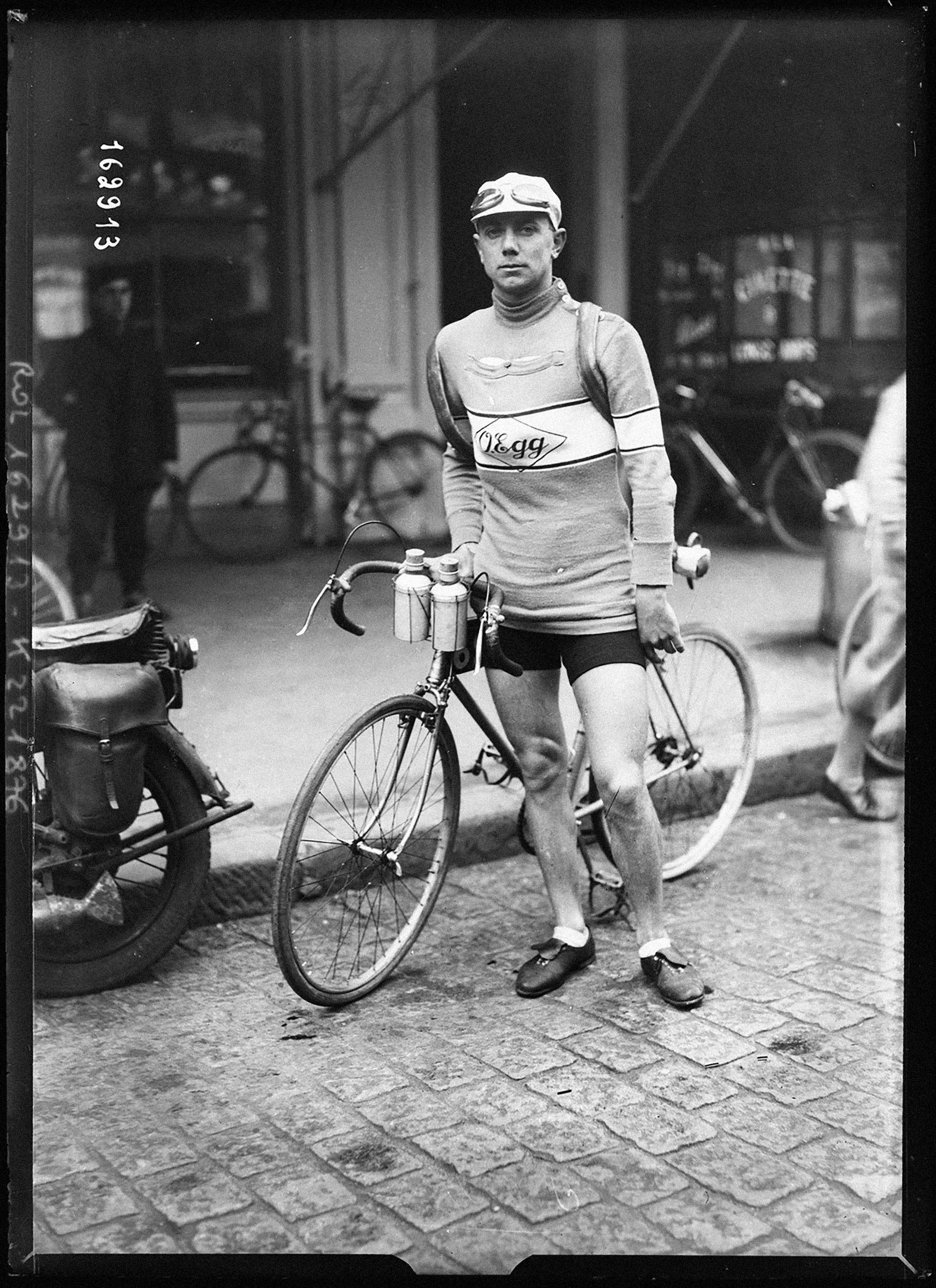

Bill Mills pictured at the 1932 Circuit de Paris

(Image credit: Agence Rol)

The story begins

My interest in Bill Mills was piqued when I received a query from an Italian journalist who was working on a project about the World Championships. Mills had been the first Briton to enter the pro road race, in Rome, 1932. A crash had seen him ambulanced out of the race. I couldn’t help, I didn’t know much more. I had seen Mills’s name in a few cycling books about other riders, but none focused on him or imparted much about him.

I decided to see what there was to learn, and set about chasing his ghost through the digitised corridors of Gallica, the French national archive. There, I learned about his brief time with the Oscar Egg team: a single season, just a handful of races. There was a temptation to call a halt there, mark him down as a rider whose ambition exceeded his abilities, one of the many who had tried to make it as a pro but failed. But Mills hadn’t let it end there.

Turning pro had been a one-way ticket for Mills; going back to being an amateur was not an option. After 1932, he could have moved on to something new, but he chose to teach others, drawing on his own experience. He started proselytising for the European way of doing things, championing mass-start racing. Backing his words with actions, in 1933, along with Vic Jenner, he organised a mass-start race on the Brooklands motor-racing circuit in Surrey, a breakthrough moment for British cycling. This race effectively marked the end of the dark ages the sport had retreated into over the previous three decades. More closed circuit races followed, on the Isle of Man’s TT circuit and in Crystal Palace.

Mills went further in 1936, launching a magazine, The Bicycle – a rival to Cycling Weekly (or Cycling as it was called back then) – in which he championed the charms of European-style racing. It paid off. Charlie Holland and Bill Burl entered the Tour de France in 1937, having come through races Mills had helped to organise. It took an 11th-hour assist from Mills to get Tour de France founder Henri Desgrange to allow them to start, but start they did – as the first Brits ever to appear in the race.

Burl abandoned on the second stage, while Holland made it as far as the Pyrénées, stage 14, before having to quit. In subsequent years, neither rider showed any interest in returning to the Tour to try again. Nonetheless, Mills pressed on, determined to push the door wide open for British riders to participate in the Tour. Visiting the race in 1939, he spoke to L’Auto about his plans: “The record craze having passed in England, I hope to be able to bring you a solid team next year. Perhaps it won’t do sensational things in the first year, but we have to start off on the right foot.”

Mills’s plans for the 1940 Tour withered on the vine. War broke out, and by the time the Tour returned in 1947, British cycling had suffered a schism. In 1942, Percy Stallard and his rogue heroes in the British League of Racing Cyclists (BLRC) broke away from the National Cyclists’ Union (NCU) primarily over the issue of mass-start road racing, which the NCU opposed, fearing conflict with the police. It was one step forward and many steps back for Mills’s dream. The BLRC riders were excluded from the Tour, with only NCU riders officially recognised by the UCI. It was 1955 before a truce could be reached, allowing riders from both bodies to enter the Tour.

Unsung hero

Mills died in 1965, aged 58, a few months before Tom Simpson followed his pioneering first pro road race at the Worlds by winning the rainbow jersey. Writing in this magazine, the legendary cycling journalist Jock Wadley – who had got his break writing for Mills’s The Bicycle – paid homage to his old boss for inspiring him to become a cycling journalist, adding: “I am just as convinced… that Brian Robinson, Tom Simpson, Alan Ramsbottom and co. owe their professional careers to his early efforts. British cycling was very narrow in its outlook until he came along with his bright ideas.” It was through Mills, Wadley pointed out, that “the club world first learned of the magnitude of Continental cycling”.

Without Mills, who knows how much longer it might have taken for Britain to get a toehold into road racing on the world stage. Yet few British cyclists today even recognise his name. The floor of history’s edit suite is littered with people like Bill Mills, men and women who made a difference but whose stories have been cut from the final edit – catalysts of change surpassed by glitzier stars. While Percy Stallard takes all the glory for ending British cycling’s years of isolation, Mills, if he is remembered at all, is regarded as a bit-part player.

The thing about history, though, is that there is always room for a different version of the story to be written, an alternative cut. One day, perhaps Bill Mills will be recognised for what he was: a man who pushed British cycling to take its first step toward victory in the Tour de France. A man who dared to dream of yellow before Britain believed it possible.

Alfredo Binda (centre) at the 1932 World Championships

(Image credit: Shutterstock)

Tilting at Mills: Family history hits the road

Bill Mills’s great-niece Angela Mills-Bannon has been undertaking epic rides in homage to her great-uncle.

A former rower, Mills-Bannon took up cycling a few years ago and has completed charity rides, including London-Paris in 2023, in which she helped raise more than £24,000 in aid of Cure Leukaemia. In 2024, she rode the UCI Gran Fondo World Championships and again rode London-Paris. In doing so, she echoed aspects of her great-uncle’s career: he rode the Worlds in 1932 and, in 1947, with Jean Leulliot – the man behind Paris-Nice and the first attempt at a women’s Tour de France – organised a race from Paris to London.

This year, Mills-Bannon – who posts about her adventures on Instagram as @1930sbicycle – is further following in her great-uncle’s wheel-tracks by riding the full course of the Tour de France Femmes, one day ahead of the race itself. From old copies of The Bicycle passed down to her father, she has also been learning about how Mills championed women’s cycling and has taken inspiration from his efforts to get British riders into the Tour.

Along the way, Mills-Bannon will pass through Angers, providing a chance to reflect on Paris-Angers, a race Mills completed in his Oscar Egg jersey in May 1932. Around Montreuil, the routes of the 1932 and 2025 races will converge, and as Mills-Bannon presses on for the final 10km of the stage, she will be carried along in her great-uncle’s spectral slipstream.

The full, original version of this article was published in the 22nd May 2025 print edition of Cycling Weekly. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered direct to your door every week.

Explore More