The number of North Atlantic right whales has grown slightly, continuing a recent positive trend that has researchers “cautiously optimistic” about the critically endangered species.

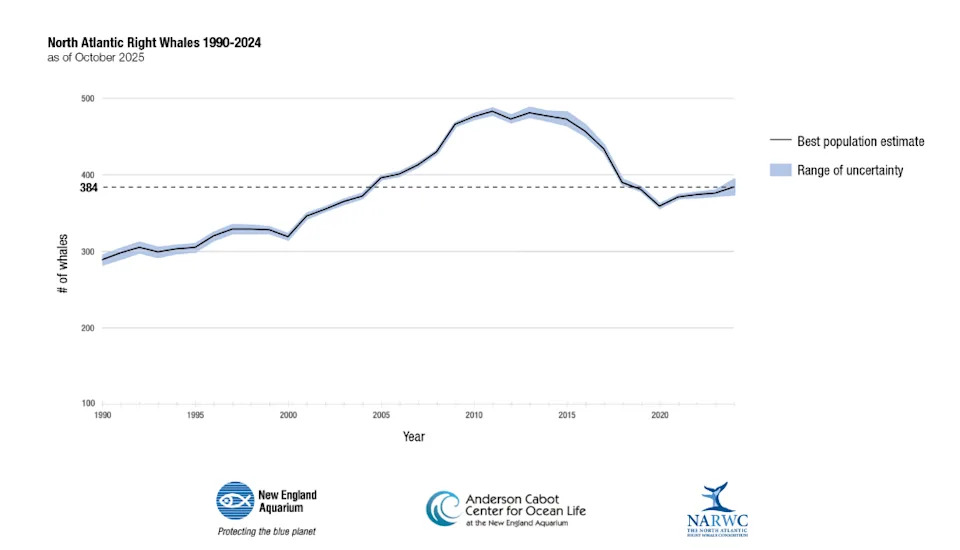

The whale population increased to about 384, up from around 376 the year prior, according to estimates released by The North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium on Oct. 21 ahead of the group’s annual meeting. Estimates are done in retrospect, so the most recent numbers are for the 2024 population.

Several whales giving birth for the first time coupled with no detected deaths and fewer significant injuries left Heather Pettis, who has studied right whales for 25 years, “feeling thrilled.”

“It’s sort of the trifecta of good news for the population, which is really just encouraging and exciting to share,” Pettis, chair of the consortium and a senior scientist in the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center, told USA TODAY.

North Atlantic right whale ‘Monarch’ (catalog #2460) was observed with her new calf in Cape Cod Bay in April 2025.

Right whales were heavily hunted until the 1960s – when the International Whaling Commission began to ban commercial whaling – and landed on the endangered species list in 1970. They’re called right whales because whalers once considered them the “right” whale because they were easy to hunt and floated after being killed.

The whale population rose to an estimated high of 481 in 2011 but soon took another sharp decline, plummeting to an estimate of fewer than 350 animals in 2020. The whales are identified by unique natural markings and catalogued in a collection the center maintains of more than 2 million photos dating back to 1935.

How long can right whales live? Study extends their lifespan estimate

Even with the recent uptick, Pettis said strong protection measures are still needed in both the U.S. and Canada to ensure the population has a chance to rebound. Though researchers logged no right whale deaths in the latest report, entanglements and vessel strikes remain a serious threat to the animals.

“They’re definitely not out of the woods,” Pettis said. “We’re talking about a population of 384 animals. It’s still really small. They’re really vulnerable.”

Researchers spotted only one whale with new injuries due to entanglement, but cautioned more could be detected in the final months of the year.

This chart shows North Atlantic right whale population trends from 1990-2024.

“Detecting entanglements is challenging as it requires two things to align: people to be looking and whales to be present in those times and locations where they’re looking. That’s why it is so important to have continued collaboration with state, federal, and private entities to ensure right whales are monitored throughout their range in the U.S. and Canada,” Philip Hamilton, a senior scientist in the Anderson Cabot Center, said in a statement.

Meanwhile, the numbers of calves born has lagged behind what researchers hoped. The scientists said whales gave birth to eleven calves in the last season, including four first-time mothers.

Some biologists have estimated it would take roughly 40 new calves a year and fewer than one human-related death for the endangered right whale to rebound. Pettis said the real concern is what percetange of the female population is reproducing. She said some of the 72 reproductive-age females in the population have been giving birth later in life than expected, and researchers are hoping to see more of the younger animals produce offspring.

Pregnant right whales are gearing up for their annual migration from waters off New England and Nova Scotia to the waters off Georgia and Florida where they give birth each winter. Their babies can weigh in at about 2,000 pounds and measure 15 feet long.

Though most of mother-calf pairs are spotted near the southeastern United States, this past season two mothers and calves were seen for the first time off New York and in Cape Cod Bay. Pettis said as climate change has warmed ocean waters, the whales have moved into new locations to follow their food sources.

“What we always say is that it’s a really resilient species,” said Pettis. “They know how to adapt.”

Contributing: Jennifer Borresen, USA TODAY

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Endangered right whales get a ‘trifecta of good news’ in 2025