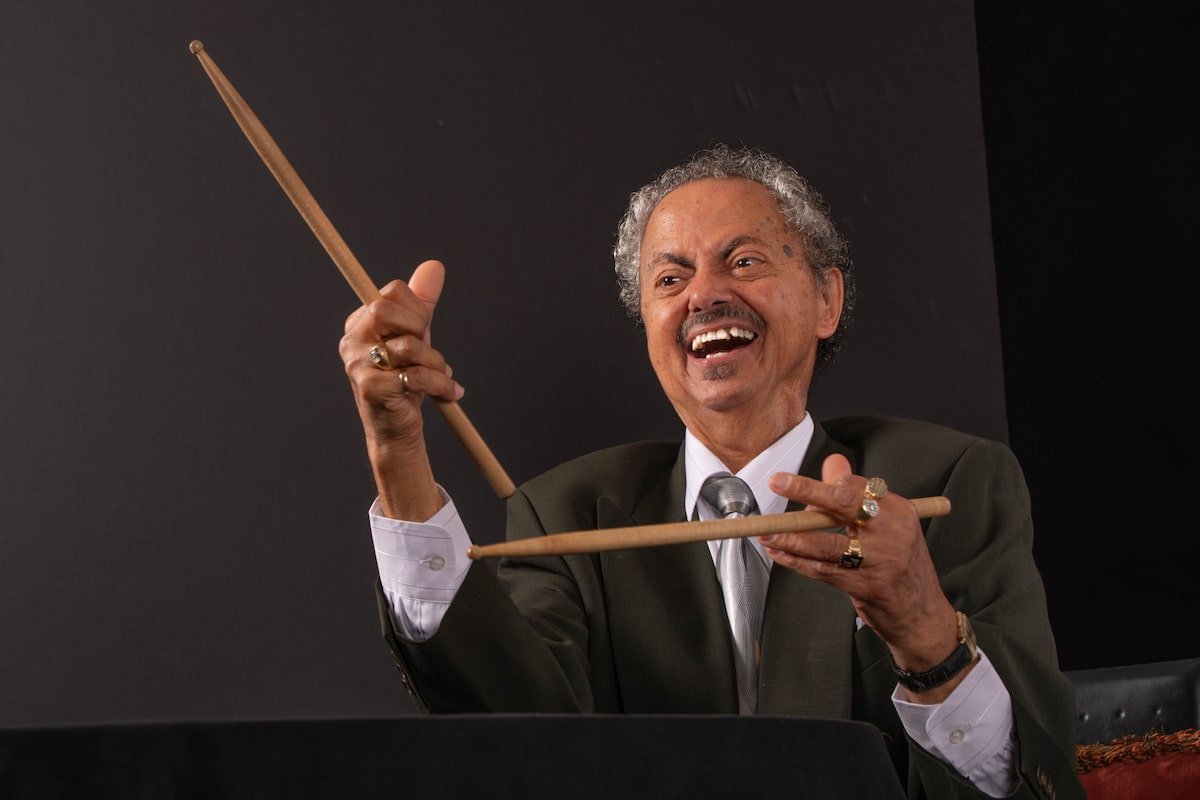

The self-taught drummer modeled his exciting hard-driving style after Art Blakely, Elvin Jones and Max Roach.Marie Byers/Supplied

Born and raised in Montreal, Norman Marshall Villeneuve was taught to tap dance by his older brother. As a preteen he studied piano with the great instructor Daisy Peterson-Sweeney, sister of Oscar Peterson. Another legendary jazz pianist, Oliver Jones, was a cousin who, like Mr. Peterson, lived nearby.

The tutoring in the other disciplines notwithstanding, he instead became one of Canada’s greatest bebop drummers.

Mr. Villeneuve, a masterclass in motion who brought an exuberant manner, a deft, quick touch and an impressive rhythmic ambidexterity to his craft, died July 9, at Montreal’s Lachine Hospital. He was 87 and had suffered a stroke.

The self-taught timekeeper modeled his exciting hard-driving style upon the likes of U.S. icons Elvin Jones, Max Roach and, most significantly, Art Blakey.

Mr. Blakey, beyond his polyrhythmic expertise, was important as a bandleader and a mentoring talent scout. Mr. Villeneuve took that role to heart, calling his own band Norman Marshall Villeneuve’s Jazz Message, in honour of Mr. Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

Mr. Villeneuve was something of a one-man finishing school for the young musicians who passed through the ranks of his band. On a more formal level, he created the Norman Marshall Villeneuve Scholarship, first at Toronto’s Humber College and, after he returned to Montreal, with Concordia University.

“I never went to a music school or learned how to read music properly, which held me back from doing studio and big band work,” Mr. Villeneuve said in 2018. “I respect these youngsters and want to help if I can, so they don’t have to go through that.”

As a live performer, Mr. Villeneuve was a consummate entertainer and a musical catalyst. “The harder he plays, the better the band sounds,” former Globe and Mail jazz critic Mark Milley wrote in 1994.

“When he was having a good night, he lifted everybody up,” said pianist David Restivo, a one-time member of Mr. Villeneuve’s band. “To match his intensity, you brought your A-game − everybody did.”

He grew up in Montreal’s Saint-Henri neighbourhood, which was near the Little Burgundy community referred to as the “Harlem of the North” and considered one of the jazz meccas of North America. His foster brother Charles Griffith gave him his first set of drums at age 14, around the time when he began to study the technique of Mr. Blakey.

“He could swing you into bad health,” Mr. Villeneuve said of the bebop pioneer in an interview with The Globe in 1994. “Put anybody on the bandstand with him and he’d make them work. That’s the thing that first caught my ear when I started listening to him in 1952-53. That’s the way I learned how to play – by listening to him.”

He landed his first full-time gig at 17, playing six nights a week in a Montreal restaurant and touring the Quebec countryside. In 1955, his acclaimed pianist cousin Mr. Jones invited him to perform on a CBC radio broadcast series.

The clubs Mr. Villeneuve played represent a vibrant bygone era of the city’s jazz history: Biddles, Café La Boheme, the after-hours Black Bottom and, most importantly, Rockhead’s Paradise.

The nightclub founded by Jamaican entrepreneur and former railway porter Rufus Rockhead helped launch the careers of Mr. Peterson, Mr. Jones, Billy Georgette and others. Ella Fitzgerald made her first Montreal appearance there in 1943. Famous patrons included Pearl Bailey, Sammy Davis Jr., Louis Armstrong, humourist Stephen Leacock, prizefighter Joe Louis and the entire Harlem Globetrotters basketball team.

In the early 1960s, Mr. Villeneuve joined the house band at Rockhead’s Paradise, keeping time for the likes of bandleader-trumpeter Allan Wellman, bass player Nick Aldrich and pianist Linton Garner. Though charming, Mr. Rockhead was a hard-headed employer.

“Every second Sunday at 12 o’clock you had to be upstairs at the Rockhead’s on the bandstand,” Mr. Villeneuve said in 2022. “Don’t come late or you’d have to buy somebody something.”

Opportunity knocked in 4/4 time in 1967 when none other than Duke Ellington invited Mr. Villeneuve to try out for his band in Boston. He passed the audition. “It felt good,” he later told the Montreal Gazette. “I wasn’t scared or nervous. I just played the way I felt the music.”

Unfortunately, he couldn’t secure a U.S. work permit. The prized gig went to another drummer; Mr. Villeneuve would keep the formal job offer from Mr. Ellington displayed prominently on his apartment wall for years after.

In 1974, he moved to Toronto, where he was a fixture on the local jazz scene and a father-figure to younger players at rooms such as Bourbon Street, The Montreal Bistro, Top o’ the Senator, the Pilot and the Rex Hotel Jazz & Blues Bar.

Critiquing an appearance by a quintet led by Mr. Villeneuve in 1995, The Globe’s Mr. Miller praised the drummer: “His cymbal rides were resolute and his snare-drum strokes ricocheted like gunshots on the floor around a soloist’s feet.”

Over the course of a 72-year career, Mr. Villeneuve mostly performed in the country’s two largest cities. He did tour internationally with his cousin Mr. Jones however, once living in Puerto Rico for nearly a year during an extended arrangement at the Carioca Lounge of the Americana Hotel in San Juan.

His death leaves a mentorial void in the insular Canadian jazz community. Informal apprenticeships historically were vital to the jazz ecosystem, well before bebop was taught in postsecondary institutions.

“We got the benefit of that with Norm and others,” said pianist Mr. Restivo, also an instructor at British Columbia’s Selkirk College. “It’s up to us now, we have the responsibility. Otherwise it dies.”

He was born in the Montreal borough of Verdun on May 29, 1938, when swing orchestras led by Tommy Dorsey and Artie Shaw ruled the charts and singers such as Bing Crosby and Ms. Fitzgerald (A-Tisket, A-Tasket) were the pop stars of the day. Mr. Villeneuve came of age during the jazz revolution that brought bebop: The birth of cool.

Mr. Villeneuve was a mixed-race child − his white mother’s maiden name was Marshall − brought up from the age of seven in a loving Black foster family led by Alonso and Josephine Griffith. He learned both piano and religion at Union United Church, believed to be Canada’s oldest Black congregation.

For the first two decades of his career the drummer played in R&B bands, rock ‘n’ roll groups and in strip clubs, as jazz gigs alone wouldn’t pay the bills. Rock music, he would say later, “didn’t appeal to me.”

In the late 1960s, he had a 37-month job (six nights a week, 9:30 p.m. to 2:30 a.m.) with guitarist Nelson Symonds and bassist Charlie Biddle at Café La Bohème. Mr. Symonds attracted locals, tourists and some big names. In his 2017 interview with the Montreal Gazette, Mr. Villeneuve recalled the visit of a young Motown phenom.

“I was here, and guess who was sitting there?” Mr. Villeneuve said, pointing to a stool a few feet away. “Stevie Wonder. Apparently he heard about this fabulous guitar player.”

Later in his career, in Toronto, the drummer worked as a maintenance man at a senior citizen’s home for a steady pay cheque, accepting jazz gigs as they came.

“I’m not doing this because I’m thinking I can make a whole lot of money,” he told The Globe, speaking about forming his namesake band. “I’m doing this because I love to play.”

Drummer Ted Warren was using a rented Ludwig drum kit one night at George’s Jazz Room in Toronto when he met Mr. Villeneuve in the 1990s.

“It was the first time I played there, and he asked me if the drums were Ludwig, even though he was sitting in a spot in the room where he couldn’t see me,” Mr. Warren said. “It was very unusual. Strange, almost.”

If Mr. Villeneuve wasn’t at the drum kit himself, he was watching others. Mr. Restivo remembers Mr. Villeneuve soaking in one his drum heroes in Toronto in 1991.

“I can still see him sitting directly under Elvin Jones’s ride cymbal at the Bermuda Onion club, eyes closed, lost in a reverie of groove and sound and flow.”

He returned to Montreal in 2013. His last gig was a weekly Friday night appearance at the House of Jazz in 2020 that came to an end because of COVID-19.

Mr. Villeneuve’s 2017 album Montreal Sessions compiled live recordings from Rockhead’s Paradise and the Black Bottom. The material dating back to 1963 featured Mr. Symonds, Mr. Wellman, Mr. Biddle and others.

Mr. Villeneuve is survived by his wife, Louise Villeneuve, and brother, Irvin Griffith. His children from previous marriages are Deborah Villeneuve, Norman Villeneuve Jr., Niles Villeneuve and the predeceased Tiffany Lovey.

You can find more obituaries from The Globe and Mail here.

To submit a memory about someone we have recently profiled on the Obituaries page, e-mail us at obit@globeandmail.com.