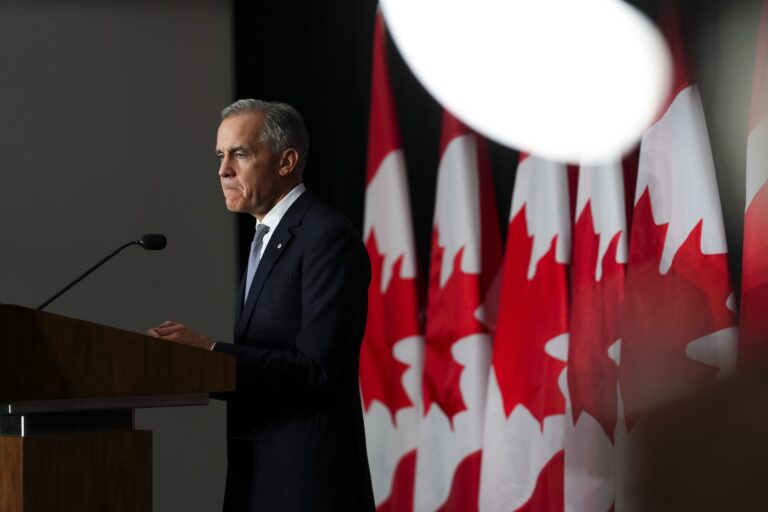

When former prime minister Justin Trudeau’s government flushed Chinese investors out of the Canadian mining industry a few years ago, it justified its assault on the free movement of capital as a matter of national security. “We will act decisively when investments threaten our national security and our critical minerals supply chains, both at home and abroad,” said François-Philippe Champagne, who was industry minister at the time.

Ottawa’s stridency when it comes to autocratic governments buying influence in Canadian mining has softened since then.

The personality cult that leads an openly hostile regime recently authorized the purchase of a five per cent stake in Vancouver-based Lithium Americas. Its newly renamed Department of War then bought US$35.6 million of shares in another Vancouver-based miner, Trilogy Metals. The military of an unfriendly government now owns 10 per cent of Trilogy’s shares, enough to secure rights to appoint an independent director to the company’s board.

Related Articles

You’ve identified the foreign entity as the U.S. government, increasingly dominated by President Donald Trump and his MAGA movement. These transactions appear to be part of a grander plan. Earlier this year, Halifax-based Ucore Rare Metals announced that it had received US$18.4 million from the War Department to deploy its newly developed separation technology at a site in Louisiana. “We’re looking at this as a Manhattan Project,” Ucore chief executive Pat Ryan told The Wall Street Journal.

Trump has been credibly accused of wanting to break Canada’s economy. Five years ago, Trump hobbled the ambitions of Canada’s aerospace industry. Now, he’s going after the automotive and forestry sectors. Last week, Trump said he was increasing duties on Canadian imports because he disliked Ontario’s anti-tariff ad featuring Ronald Reagan.

MAGA has turned the elected legislature into something akin to a ceremonial body where the Republican majority does the bidding of the leader. Trump talks seriously about wanting to absorb democratic states. His administration displays a troubling disregard for human rights and cronyism. The U.S. now regularly assaults the global norms by which Canada lives.

Yet we appear to be OK with such a regime getting between Ottawa and a strategic industry. “Capitalism in action,” Energy and Natural Resources Minister Tim Hodgson said.

But not capitalism as we’ve come to know it.

Prime Minister Mark Carney talks of a rupture with the U.S., but it’s not obvious that Canadians have absorbed what that could mean. Yes, we need to build. But we also need to rethink the consensus on which we’ve based economic policy for the past couple of decades. To what extent can we trust markets and private interests when states such as the U.S. and China exploit them to exert power? Is a belief in fiscal prudence too precious for a world dominated by state capitalism? If we still believe in the power of free trade, who are our friends?

It’s hard to escape the feeling that a reckoning is coming. Blayne Haggart, a professor of political science at Brock University, likens it to that moment in a horror movie when the protagonist proceeds to the basement even though it’s obvious that something terrible is going to happen. Haggart, who studies North American politics, thinks Canadians are engaged in an “unacknowledged debate” over the nature of the U.S. threat, and by extension, the best way to respond.

Haggart is on the side that believes the U.S.’s authoritarian turn started before Trump decided to run for president and that it will continue after he’s gone. The U.S. response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks was a preview. MAGA spiritual leader Steve Bannon’s recent claim that there are “many different alternatives” to get Trump an unconstitutional third term might foreshadow what’s yet to come.

An important variable in the 20th-century debates that led to Canada’s relative embrace of freer markets and smaller government was the prospect of a collaborative relationship with the world’s dominant economy. The U.S. political system is now indifferent, and maybe even hostile, to Canada’s “win-win” arguments for free trade. “The United States no longer seeks to be first among equals, or even to have Canada as a junior partner,” Haggart said in the text of a presentation he gave last week in St. Catharines, Ont. “It seeks domination. Any agreement with the U.S. will reflect those terms.”

The mining industry is a microcosm for thinking about all of this.

It gets harder by the day to argue that the Trump administration is any less of a threat to Canada than Xi Jinping’s regime in China. Both countries exhibit a volatile mix of menace and opportunity, yet we treat them very differently.

In November 2022, Trudeau ordered Chinese companies to divest their stakes in three Canadian miners. It was a purge. Two of those Canadian miners had domestic operations, but a third—Calgary’s Lithium Chile—said it owned no Canadian mineral assets. Champagne forced out its Chinese investors anyway.

The U.S. government now has direct influence over a set of Canadian miners. So far, Carney is taking a softer line on the MAGA movement than on the Chinese Communist Party. The threat might be lower. Though Lithium Americas and Trilogy Metals are Canadian companies, their mines are in American states. But that distinction didn’t matter in Trudeau’s purge of Chinese ownership.

Haggart’s view was formed from a great distance. That offers the advantage of perspective but might miss what is actually happening on the ground. Hugues Jacquemin, chief executive of Ottawa-based Northern Graphite, said that what he sees are officials from NATO countries working in concert, and at pace, to break China’s stranglehold on supplies of critical minerals.

Jacquemin acknowledged that Trump’s politics are a reason for pause. But ultimately, he said, he thinks the U.S. and Canada are too intertwined to break apart. He sees the U.S. government’s decision to purchase stakes in miners as an attempt to jumpstart production outside of China, not as a means of foreign interference.

“One of the major problems we have in the critical mineral space is the fact that we’ve lost investor confidence, and so we have to restore that,” Jacquemin said. “What the [U.S. government] is trying to do, that’s my view, is they’re trying to restore some investor confidence by investing themselves and showing the way.”

Jacquemin’s observation hints at a solution, but a country that idealizes budget surpluses and free markets won’t like it.

The U.S. might feel less compelled to exert its influence on non-American miners if it didn’t think they needed help. It appears to have given three Canadian miners a boost of something like $100 million. That might seem like a lot of money. We’ve been lectured for decades on the folly of using public money to prop up private industry. But consider that the Ontario government paid $75 million just for that Reagan ad campaign. Makes you wonder if there are better ways to stand up to the Trump administration.

Kevin Carmichael is The Logic’s economics columnist and editor-at-large. He has spent more than two decades covering economics, business and finance for outlets including Bloomberg News, The Globe and Mail and the Financial Post, where he also served as editor-in-chief.