Key Takeaways:

● Gambling Indictment Shocks Sports World

● Lappartient Feathers His Own Nest – But For What?

● Gravel Racing Needs More Focus on Safety

● Strava Plans for IPO

● Looking Ahead to the 2026 Tour

The NBA gambling indictments and arrests last week landed like a broadside on global sporting integrity, raising deep questions about the exponential growth of sports betting, and confirming the worst fears of sports analysts and pundits. An investigation which started with lifetime-banned NBA player Johntay Porter led to an additional arrest – that of highly-regarded journeyman Terry Rozier – and seems likely to ensnare additional players who either provided inside information to bookmakers or otherwise influenced betting lines or outcomes through poor or reduced play. A parallel investigation led to the arrest of Hall of Fame player-turned-coach Chauncey Billups, who allegedly participated in an underground high stakes poker scheme in which games were rigged, defrauding the gamblers that Billups and others recruited.

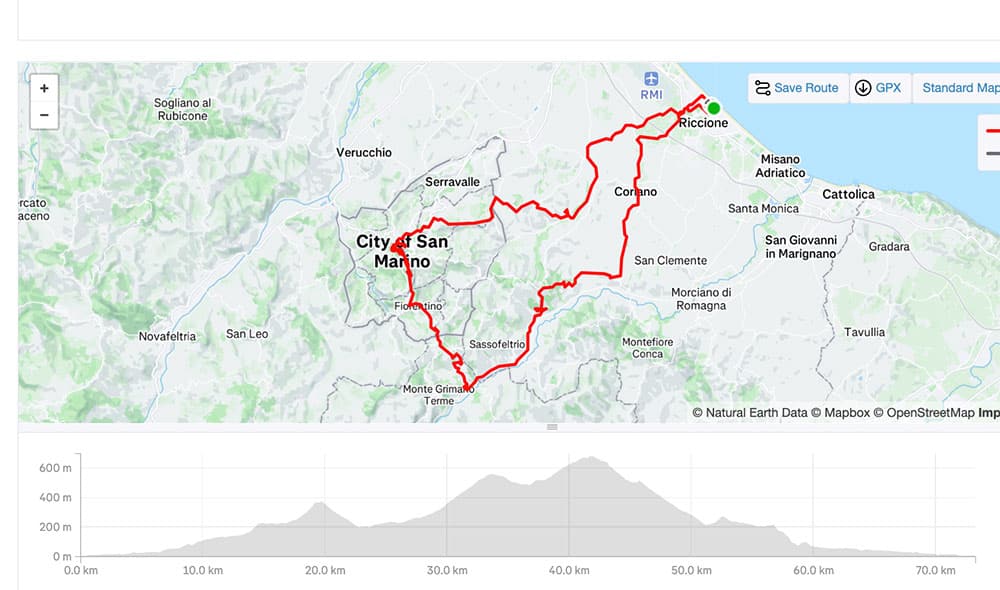

The influence of organized crime on sports betting has been a broadly known scourge, at least since Major League Baseball’s 1919 Chicago “Black Sox” scandal – when the heavy favorites deliberately tanked in the World Series in exchange for payment from a mob boss. A long history of match-fixing has underscored the influence of crime rings in professional soccer leagues; this has even been a keynote topic in sports governance conferences like Play The Game. Even tennis has had its fair share of fixing scandals in the modern era, with many pros banned for influencing outcomes of tournaments at the behest of betting syndicates. But the NBA has been a hotbed of suspicion, especially since referee Tim Donaghy went to prison in 2008 for calling fouls that influenced game outcomes and betting lines for an organized syndicate – including games on which he placed bets. This broad history suggests the need to more closely monitor and regulate the way in which organized crime infiltrates and poisons sports.

Players, coaches, and even referees can be quickly coerced, especially if they are already placing wagers through bookmakers; they are seen as easy “marks” who can be quickly turned if they have a gambling addiction. The promise of easy money or relief of debt – or extortion, depending on the reputation or fame of the athlete – become leverage for organized syndicates to entice or force the mark to influence future betting lines. In pro cycling, there is a very fine line between sportsmanship and cheating, as we have detailed in the past. The worst example the sport has had to weather has been the occasional accusation of race-finish payoffs and trade-outs, such as the bribe Moreno Argentin offered Greg LeMond during the 1985 World Championships or the deal offered by Alexander Vinokourov to Alexandr Kolobnev to win a two-up race for the 2010 Liege Bastogne Liege. Given the nature of the sport, and the common practice of “gifting” stage wins in Grand Tours for later favors and collaboration, cycling may be somewhat insulated from the rough ride which the NBA will face in the coming months. And the worst may be yet to come: according to many, including former bookmaking criminals, the NFL and NCAA Football may be a “Wild West” for illegal bookmaking and organized crime influence that might give legislators pause to reconsider the wisdom of under-regulating the industry.

UCI President David Lappartient has apparently, and quietly, pushed through changes in the organization’s constitution which could allow him an unprecedented fourth term in office. As uncovered by the Escape Collective’s intrepid reporter, Iain Treloar, this change was effectively buried among a number of other constitutional changes being voted upon by the UCI’s membership – which met during the recent Rwanda World Championships. This subtle change would allow Lappartient, in addition to his numerous other jobs, to likely remain for another eight years as head of the UCI. The three term limit was originally put in place by his predecessor Brian Cookson, to bring the sport more into alignment with best practices in other Olympic federations. But, as Treloar hints, there is more to this story than Lappartient simply securing his generous ($700,000 a year) job in Aigle.

As is well-known within the sport, Lappartient has ambitions that stretch far beyond cycling. Being head of an international sports federation allowed him to step up and onto the International Olympic Committee a few years ago – a rarefied privilege which is likely to continue as long as he heads the UCI. Although he was roundly defeated earlier this year in an audacious bid for IOC Presidency, the term of current President – and two-time swimming gold medalist – Kirsty Coventry will end in 2033. By extending his possible UCI reign another four years, Lappartient would conveniently still be on the IOC, and therefore nominally eligible to run again. The question that must be asked is: what if this, rather than his undying love of and commitment to pro cycling, is the reason he pushed through the constitutional change? It’s impossible to predict what Machiavellian IOC maneuverings may be in play eight years from now, but Lappartient – as a non-Olympic athlete and something of an outsider in one of the world’s most exclusive clubs – will probably never have a realistic chance of becoming IOC President. And if he views his UCI Presidency primarily as a springboard for bigger and better things which are likely unachievable anyway, how well does that serve cycling today?

Last week the Life Time Grand Prix wrapped up with the Big Sugar gravel race in Bentonville, Arkansas. The event was shortened from 100 to 50 miles due to heavy storms, and the racing was fast and furious from the gun. There was much to celebrate in the emerging “bicycle capital” of North America: series champions were crowned (Cameron Jones and Sofia Gomez Villafane), international athletes in the series are increasing and there is now a U23 division. The week after the event, Life Time unveiled the 2026 series, with a 55% increase in prize money – to $590,000 – and more emphasis on live streaming of races. Gravel has now become a discipline where the top athletes can make a living and focus full time on bike racing. However, gravel racing in general needs to simultaneously spend more energy on creating safe races for both pro and age group riders. For example, in Bentonville, there were several dangerous sections of the course with no police support, where the racers had to share open roads with cars. These safety problems exist on some level at most gravel races, and one race (Rasputitsa Vermont) has already had a rider death in an automobile collision. Without greater focus on safety, the growth of gravel will be constrained and some riders will be discouraged from taking part in events.

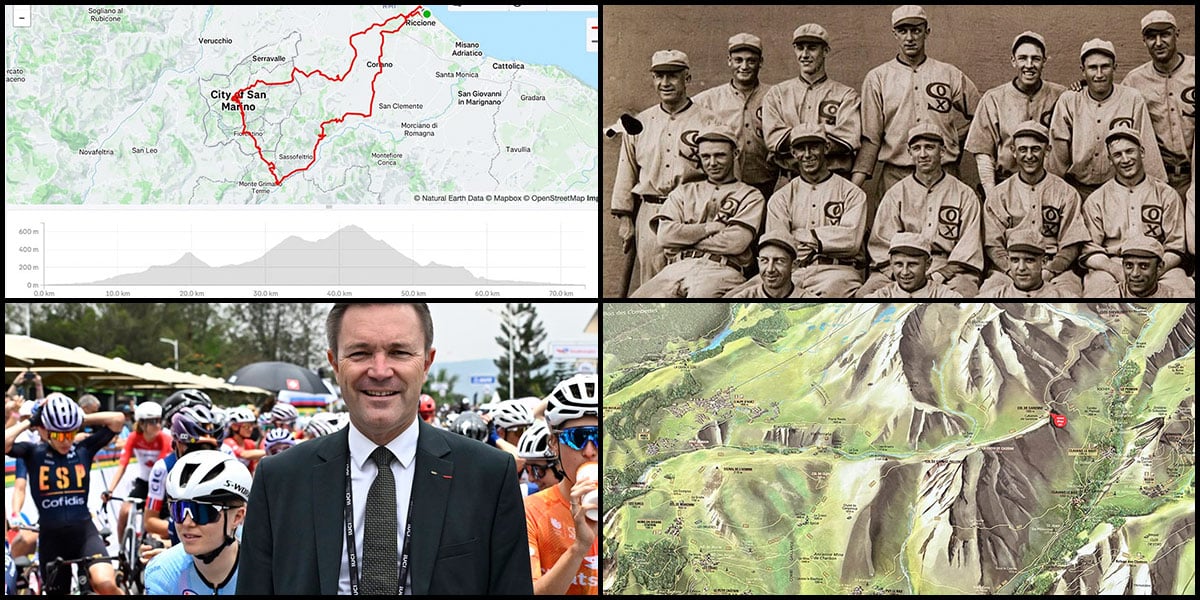

One of the classic rides I did while staying at the Hotel Dory bike hotel.

Strava recently announced plans to offer stock to the public, with an IPO planned for early 2026. Such an effort would clearly constitute a unicorn (initial IPO valued at over $1 billion) with the firm’s recent private placement investment valuing it at over $2 billion. Strava’s app has become as ubiquitous as Facebook; according to various sources, Strava is estimated to have somewhere between 50 and 150 million current cycling and running participants, using it to not only track personal athletic stats but as a means of connecting with other like individuals – almost to the level of a “dating app” directed largely at health-conscious Gen Z cohorts. The company recently announced the purchase of two other related software companies – The Breakaway and Runna – demonstrating its ongoing interest to leverage its social media pillars to upsell online coaching applications for individual athletes. The company has an estimated $500 million in annual revenues, has developed a successful “freemium” model with many compelling features, and has demonstrated high success rates for converting free subscribers into paying customers – a factor which helps drive sales for devices those customers use to connect into Strava.

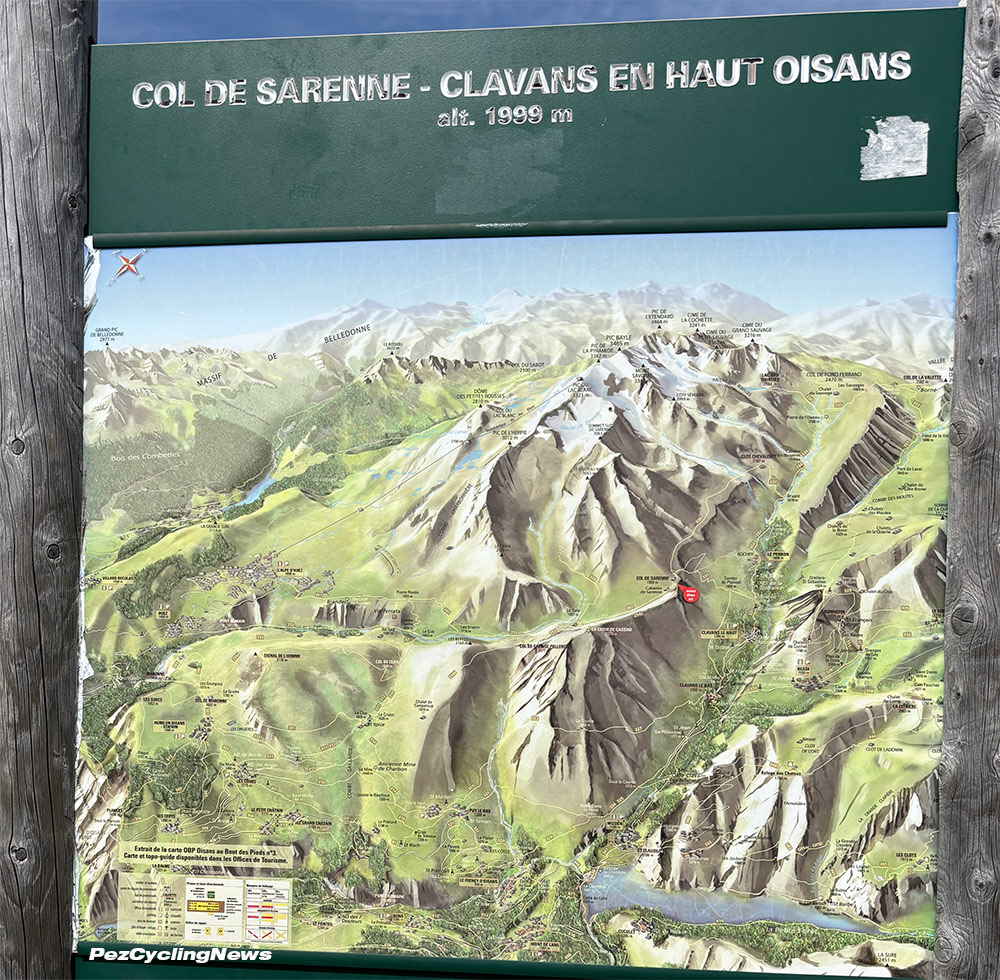

The Col de Sarenne and Alpe d’Huez are a double feature in the 2026 Tour. Read what we know so far on PEZ here.

The Col de Sarenne and Alpe d’Huez are a double feature in the 2026 Tour. Read what we know so far on PEZ here.

As professional cycling finally settled into its off-season last week, speculation about the upcoming year immediately ramped up when ASO unveiled the route for the 2026 Tour de France. By the end of the glitzy ceremony in Paris, the result was clear: a brutal course featuring eight mountain stages, all with some form of uphill finish, and a heavy emphasis on the Alps in the third week. The route includes audacious back-to-back stages featuring the iconic Alpe d’Huez and a return to the dramatic Montmartre finale in Paris, promising a spectacle over the traditional processional sprint stage. If 2025 marked a return to a more conventional slow-burn structure, 2026 is a sharp departure. The route is packed with short, explosive stages where the GC battle will begin as early as Stage 1’s team time trial in Barcelona, featuring two significant climbs and an unusual format where times are taken on individual finishers. From there, the action runs through to Stage 20, one of the hardest in recent Tour memory, before finishing atop Alpe d’Huez for the second consecutive day.

After a relatively lackluster GC fight in 2025, ASO appears to have tightened up the course for next year. This year’s edition felt weighted down by transition stages that had little bearing on the overall classification; ASO appears to have stripped out those softer days, replacing them with an early summit finish in the Pyrenees and stages through all five of France’s mountain ranges. The apparent hope is that these changes will ignite the GC battle early and keep it volatile through the final weekend in Paris. On the other hand, there is some risk that the course is so difficult, and the third week so imposing, that organizers could end up playing directly to Tadej Pogačar’s strengths, leaving little room for his rivals to ambush him along the way. Of course, we won’t truly know what the race holds until it kicks off in Barcelona in July, but the design seems rather well-suited to Pogačar, and unfriendly to Remco Evenepoel (indeed, Evenepoel’s father is even claiming, somewhat strangely, to have information suggesting Pogačar will skip the race in 2026). That seems unlikely, given Pogačar earns north of $10 million annually to win the Tour for UAE Team Emirates, but it hints at how formidable the challenge appears for anyone hoping to unseat him or Jonas Vingegaard.