The last time this writer met up with Jeff Tweedy, at a 2019 show in Brussels, the imminent release of his band’s 11th album was giving Tweedy cause to ponder where Wilco fitted in. “One of the things I think is strange about my [current] antipathy towards rock music,” he considered, “is that it’s happening at the same time as I’m becoming more confident Wilco is a rock band unlike any other still walking the earth. Does that make us a dinosaur? No, I think it’s definitely valid.”

It’s a curious, self-reflexive way of praising your band, especially when that band have been routinely lauded as one of America’s best for the last 25 years. But perhaps Tweedy’s questioning of what it means to be a rock band, and what a rock band can be, has been crucial to Wilco’s brilliance for a quarter of a century.

Over 13 studio albums, multiple side projects, hefty boxsets and a busy live schedule, Wilco’s ubiquity has been rooted in their deft, subtle way of avoiding cliché and expectations. To some, they are a cornerstone of the Americana movement, however uncomfortable they’ve sometimes been with the tag. To others, they are the much-vaunted “American Radiohead”, worrying away at rock convention with a restless desire to stretch the form. A natural successor to R.E.M., or to The Grateful Dead? Wilco accommodate it all, taking their place in a great tradition of American rock bands while playfully subverting that tradition as they go.

Success has not always felt guaranteed, however. When Tweedy formed the band in 1994, it was his old partner in Son Volt, Jay Farrar, who was widely expected to have the more significant career. Wilco’s progress for a decade was one of incremental triumphs achieved in the face of daunting challenges, both personal and professional. Their second two decades have been less tempestuous, with a long-stabilised lineup, but no less creatively rewarding. Hence the challenges of selecting their ten best albums: a band notable for their consistent excellence, in perpetual musical flux. “[The Beatles] were pushing to express themselves in ways they’d never heard anybody express themselves,” said Tweedy in 2020. “That’s basically art. That’s what I want. I want to try and find that.”

10.

Kicking Television (Live In Chicago)

NONESUCH, 2005

If Wilco’s first ten years were marked by interpersonal volatility – Jay Bennett’s tenure being especially frictional – the ensuing 19 have been strikingly solid: the lineup that came together just before these 2005 Chicago live recordings a constant ever since. Those gigging years have only seen Wilco’s flexible virtuosity increase, alongside the Grateful Dead-like command of their whole catalogue. But Kicking Television presented a band also starting at the top of their game, with Nels Cline and his needlepoint guitar lines establishing a Verlaine/Lloyd-style rapport with Jeff Tweedy. Yankee Hotel Foxtrot songs beefed up impressively, and there was a plaintive version of soulman Charles Wright’s 1969 peace anthem, Comment: “If all men are truly brothers…”

9.

Cruel Country

DBPM, 2022

Tweedy’s longtime exasperation with the Americana tag has led him to some musically extreme places, and in 2005 he told me, “[Alt-country] has become a very conservative movement that’s not really a movement. It’s stagnant.” The 12th Wilco studio album, however, archly leaned in to concepts of American roots music – and into ideas about the state of their nation. An opportunity, then, to showcase the band’s casual mastery of classic folk songwriting, but also to be slyly subversive, as they slipped an understated avant-jam into Bird Without A Tail/Base Of My Skull (think: Sonic Youth, acoustic). Cruel Country was a strategic double bluff: a self-proclaimed “country” record that was often as far as ever from being a conventional one.

8.

Wilco (The Album)

NONESUCH, 2009

Another pet gripe of Tweedy – that his fans required him to be tormented as a default – was challenged head on by the bright, liberated, sometimes rather goofy seventh Wilco album: “A sonic shoulder for you to cry on,” he promised in the self-referential power pop of theme tune, Wilco (The Song). While a fraught motorik workout (Bull Black Nova) did make the cut, Cline afire, other songs on g were Tweedy’s most Beatles-adjacent efforts since Summerteeth. The twist this time being that the sentiments of, say, You Never Know (a vibrational All Things Must Pass stomper) were ruefully optimistic rather than spiked.

7.

Ode To Joy

DBPM, 2019

A political concept album of sorts, though way subtler and more artful than the norm, Ode To Joy initially sounded like groggier kin to 2016’s mostly acoustic Schmilco. But beneath Glenn Kotche’s martial drums, a lot more was going on. “The idea of making a rock record is distasteful to me at this moment,” Tweedy told me. “We wanted to make really, really small music gigantic.” Hence “monolithic folk” songs that were both sombre and humane, anthemic by stealth, and packed with micro-detail and invention deep in the mix. Moving, too: “Remember when wars would end?” Tweedy sings in Before Us. “Now when something’s dead/We try to kill it again.”

6.

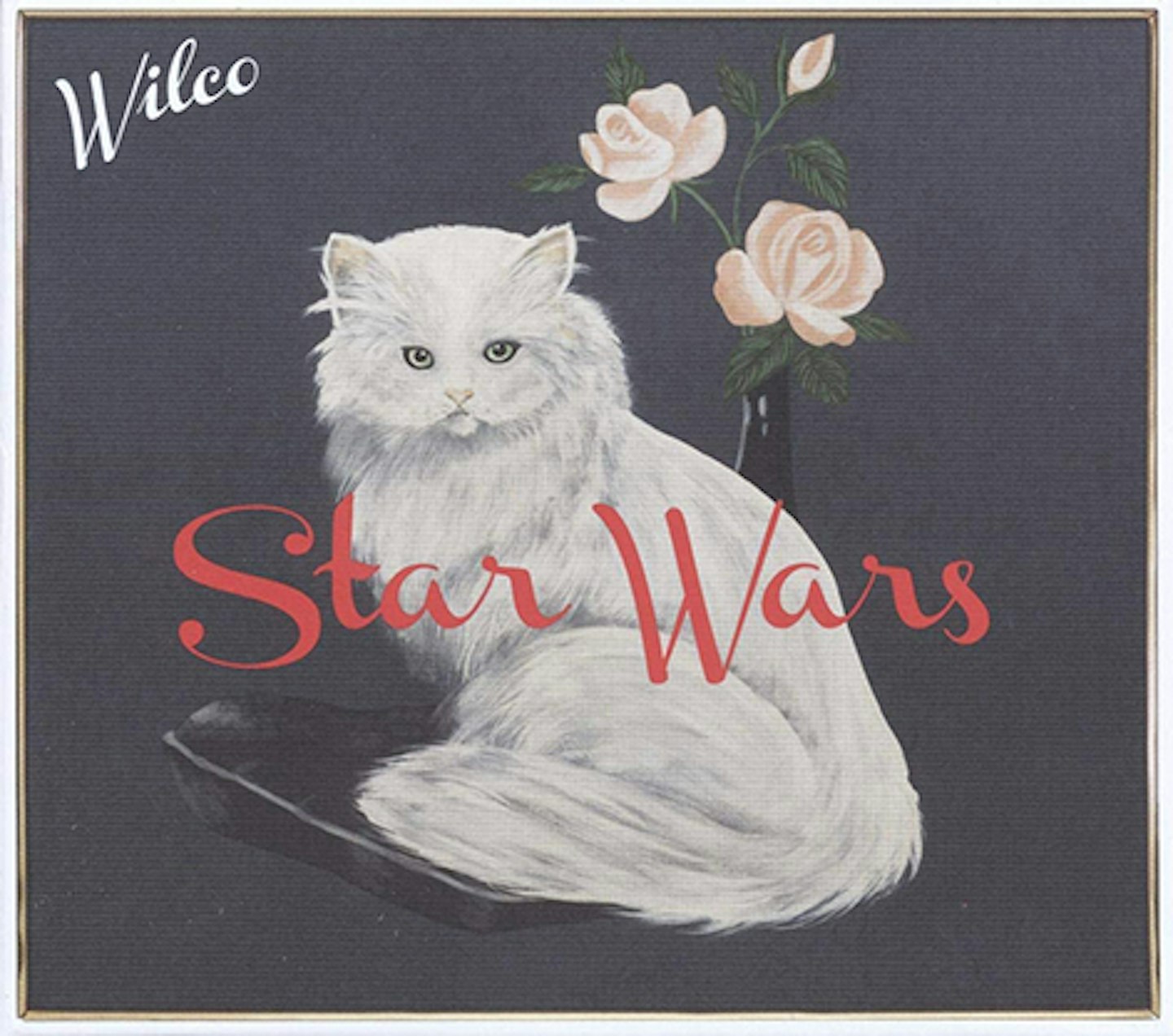

Star Wars

DBPM, 2015

A surprise release, given away online, and the band’s shortest album at only 33 minutes, Star Wars could easily be misconstrued as marginalia: even the sleeve art, a kitschy cat painting from the kitchen wall of their Chicago studio, signalled irreverence. But while the songs often veered towards sparky garage art-rock, they were terrific sparky garage art-rock. Cranked-up experimentation came compressed into three-minute gobbets and cut with nagging hooks; cf Random Name Generator, their catchiest tune since Yankee Hotel Foxtrot’s Heavy Metal Drummer. And alongside frenetic post-punk (Pickled Ginger) there were more conventional Wilco triumphs, notably the cumulative intensity of You Satellite.

5.

Being There

REPRISE, 1996

1995’s Wilco debut, A.M., had at least established Tweedy’s bona fides as a bandleader, away from Jay Farrar in Uncle Tupelo. But it was sprawling follow-up Being There that vigorously asserted he and his rapidly evolving band’s range and ambition. Alt-country still figured (Forget The Flowers was a pitch-perfect Gram Parsons homage), alongside ragged-assed Stones boogies and questing, less generic pieces like Misunderstood that would form the bedrock of the Wilco canon. Plus, an auspicious newcomer in the ranks alongside Tweedy and bass-playing lifer John Stirratt, in the shape of multi-instrumentalist and powerpop classicist Jay Bennett. His moment would come, soon enough.

4.

Sky Blue Sky

NONESUCH, 2007

The first studio effort by Wilco’s most enduring lineup – Tweedy, Stirratt, Cline, Kotche, Mikael Jorgensen (keys) and Pat Sansone (keys/guitars) – initially seemed surprisingly safe; mellow craftsmanship that could almost pass as AOR, where many expected radical fireworks. The songs, though, were some of Wilco’s most gorgeous, often co-compositions that gradually revealed themselves to be nuanced, collaborative gems. The fireworks were there, smuggled into the great tunes, Side With The Seeds and especially Impossible Germany opening up into showcases for elevated groupthink, with Nels Cline’s pointillist jazz-rock soloing to the fore.

3.

Summerteeth

REPRISE, 1999

While Wilco’s 21st century excellence has proved yet again how great art isn’t inextricably bound up with suffering, that myth fixed on to Tweedy circa Summerteeth. Wilco’s third was an elaborate chamber pop confection, bathed in the sunshine possibilities of The Beatles and The Beach Boys, but earthed in Tweedy’s personal problems: his relationship issues, drugs and, fundamentally, depression. Tweedy and Jay Bennett obsessively piled on the mellotrons to mask the trauma, but the record’s brilliance lies in its light and shade. “I was trying to figure out what the fuck I was feeling,” Tweedy told me in 2020. “But it was much easier for me to tolerate when I’d layered a disclaimer of ornamentation.”

2.

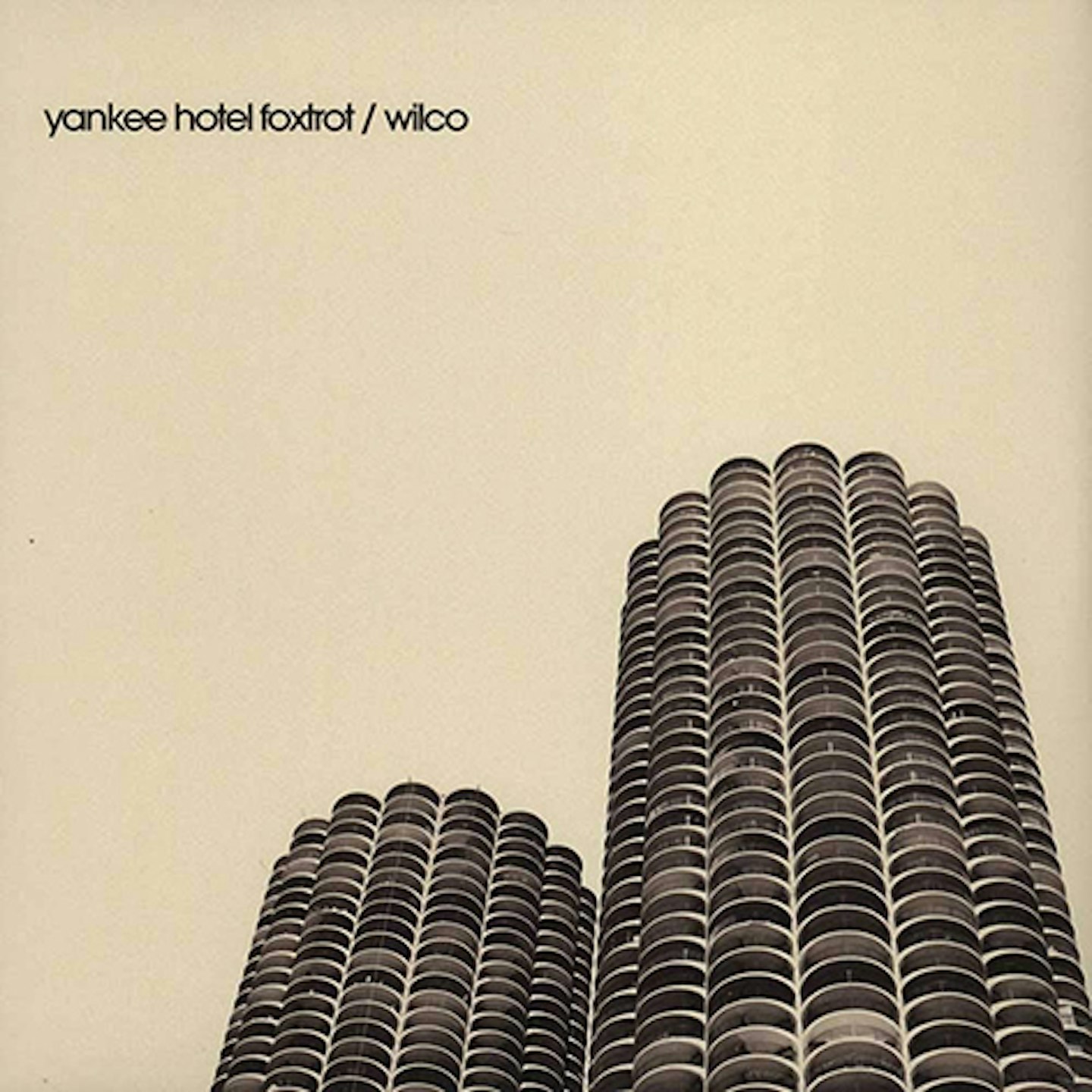

Yankee Hotel Foxtrot

NONESUCH, 2001

Another drama on multiple fronts, with protracted record label grief and a power struggle between the traditionalist Bennett and the increasingly adventurous Tweedy that only ended with the former leaving Wilco. Now, though, especially with a mammoth 2022 boxset mapping its evolution and intricacies, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot’s brilliance seems ever more distinct from its backstory. New drummer Glenn Kotche brought unorthodox rhythms, while mixer/co-conspirator Jim O’Rourke facilitated Tweedy’s experiments with process, texture and noise, his desire to escape what he later described as the “pastiche” of Summerteeth. But the radio static and conceptual dislocation ultimately complemented rather than distracted from Tweedy and Bennett’s songs: poignant, sonically fragile; a lot more resilient than they first appeared.

1.

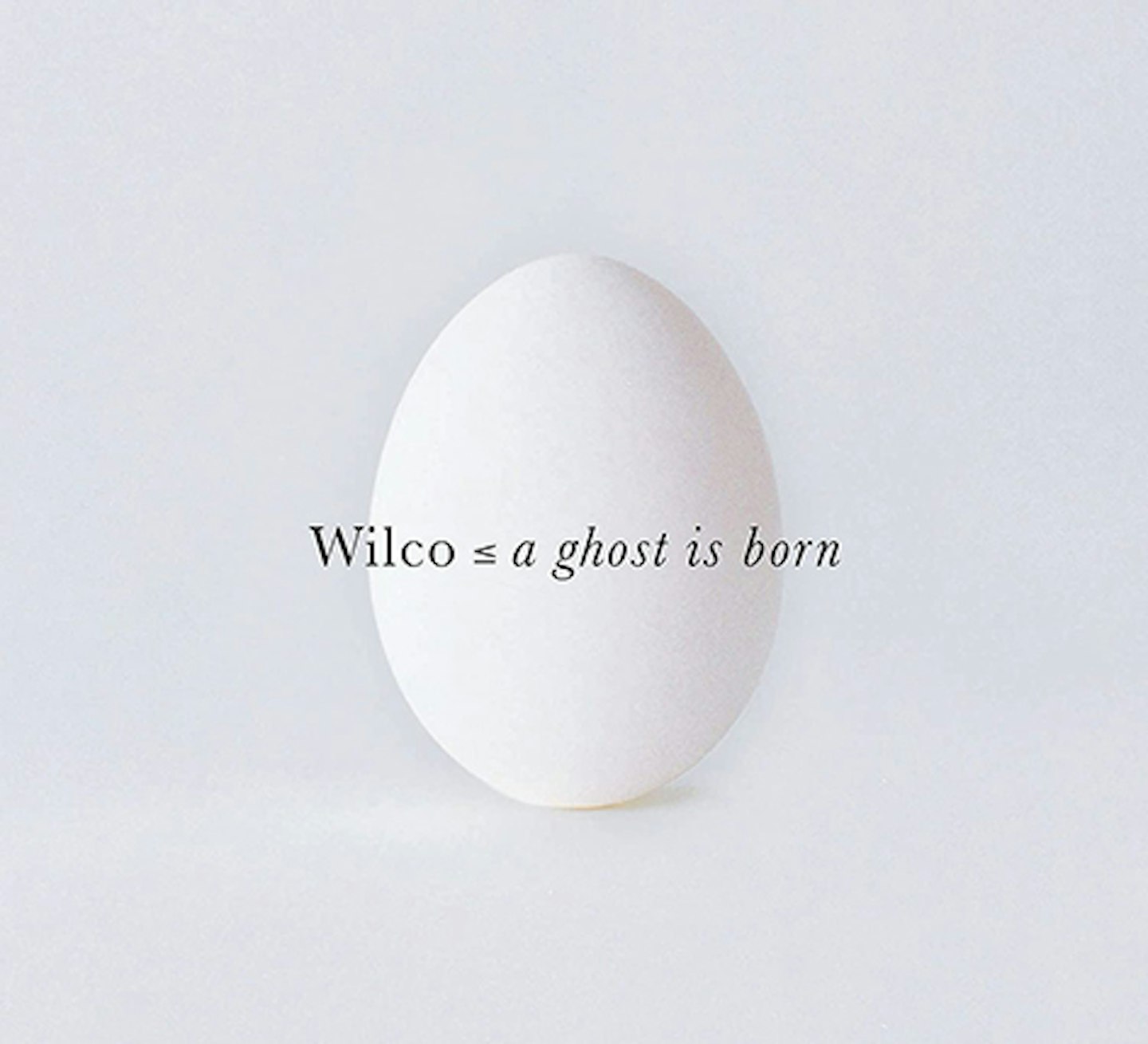

A Ghost Is Born

NONESUCH, 2004

Yankee Hotel Foxtrot is often tagged Wilco’s masterpiece, the “American Kid A” of popular acclaim. Its follow-up, though, might be even better. Record label support, Bennett’s departure, and the consensual embedding of O’Rourke as producer ensured avant-garde principles were baked into A Ghost Is Born. The sound, more organic and less processed than YHF, could accommodate Band-like country soul (Theologians) and Krautrock supergrooves (Spiders (Kidsmoke)) as well as fractured guitar improv. But Tweedy had become addicted to painkillers to combat his migraines, adding high anxiety to the spectacularly good songs: Less Than You Think, 15 minutes of uncompromising minimalist drone, was designed to mirror a debilitating headache. A fully realised and moving document of pain and addiction, immeasurably improved by the knowledge Tweedy recovered. Plus, it’s his own great guitar album: those spraying solos, pitched halfway between Neil Young and Derek Bailey, were Tweedy, not the as-yet-unenlisted Nels Cline.