A radical scheme to cool the Earth by “dimming” the sun could, in principle, help tackle global warming but it is fraught with risk, according to the Royal Society.

Britain’s leading scientific body has published one of the most detailed assessments yet of solar radiation modification (SRM), which would probably involve pumping millions of tonnes of reflective particles high into the atmosphere to deflect a small fraction of the sun’s energy back into space.

The report said there was “strong evidence” this could cool the planet but warned that “injudicious” use of the technology could push some regions into drought and worsen extreme weather.

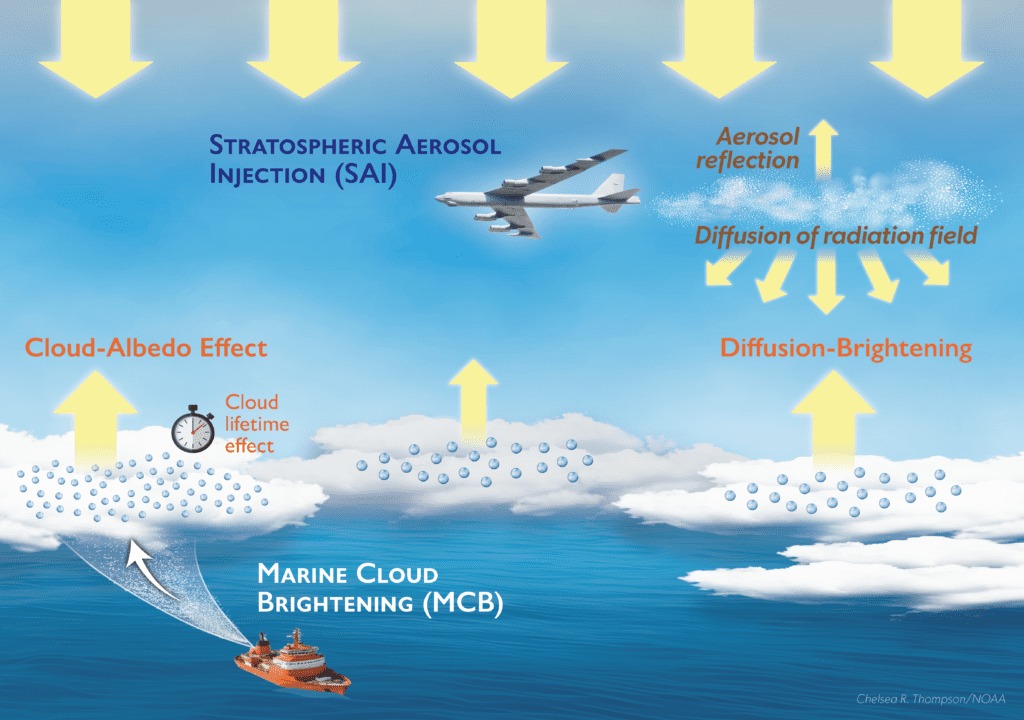

It focused on the two most widely studied methods of SRM: stratospheric aerosol injection and marine cloud brightening. The first technique would probably use aircraft to release sulphates into the stratosphere to scatter sunlight and cool the planet’s surface, mimicking the temporary cooling seen after major volcanic eruptions. The second would spray fine seawater droplets into low-altitude clouds to make them more reflective.

NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION

Aerosol injection is considered more feasible to scale up, according to the report. Confidence in the approach draws partly on the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, which injected millions of tonnes of sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere and cooled global temperatures by an estimated 0.5C for more than a year.

The UK has emerged as a significant backer of geoengineering research and the government’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) has committed £57 million to its Exploring Climate Cooling programme. The initiative places Britain among the leading nations investigating interventions such as solar radiation management.

Climate models suggest that cooling the planet by about 1C could require injecting roughly between eight and 16 million tonnes of sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere each year — a large amount but less than a tenth of the sulphur pollution humans were emitting at the peak of industrial activity in the 1980s and 1990s, the Royal Society said.

Interest in such ideas has grown as global efforts to cut greenhouse-gas emissions fell short of the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit warming to well below 2C above pre-industrial levels. Global temperatures are already about 1.2C higher and current policies are likely to push warming beyond 2C by 2100, including a one-in-three chance of exceeding 3C, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Studies have suggested that aerosol injection could cost a few tens of billions of dollars a year per degree of cooling — relatively little compared with the potential costs of unchecked global warming. However, the Royal Society cautioned that nobody knew how much cooling a given level of deployment would produce, how regional climate systems would respond or how ecosystems and societies would cope with the side-effects.

Computer models have suggested that globally co-ordinated, long-term use of SRM could lessen impacts such as sea-level rise, extreme rainfall and wildfires. Yet those models also showed it would not undo all aspects of climate change driven by greenhouse gases. It would not stop ocean acidification, which stems from rising carbon dioxide levels, and would be likely to reduce global rainfall overall.

Depending on how it was deployed, SRM could also worsen climate impacts in some regions by shifting monsoon patterns or altering storm tracks. Unlike carbon dioxide, which persists in the atmosphere for centuries, the reflective particles used in SRM would remain aloft for only months, or at most a year. Maintaining their cooling effect would therefore require continuous replenishment for decades or centuries. Stopping suddenly could trigger a “termination shock” — a rapid temperature rise of 1C to 2C within two decades, which could be devastating for ecosystems and societies unable to adapt quickly.

Monitoring and verification would also be difficult. Detecting the influence of SRM against a background of natural variability could take years or even decades. The report concluded that SRM cannot be the sole policy response to climate change. However, it suggested, SRM could buy time while the world moves to cut greenhouse-gas emissions.

Professor Keith Shine of the University of Reading, who led the assesment, said: “SRM is clearly not without risks. However, there may come a point where those risks are seen to be less severe than the risks of insufficiently mitigated climate change.”

The UN has warned that the Earth is on course for “climate breakdown” despite new plans to curb carbon emissions backed by Britain and more than 60 other countries. Sir Keir Starmer will join Prince William in the Brazilian Amazon on Thursday ahead of the Cop30 climate conference, which the UK has buoyed by being among the first nations to declare a 2035 emissions target.

However, the UN environment programme (Unep) found a large gap between the 64 national climate plans submitted ahead of the summit in Belem and the world’s goal of holding global temperature rises to 1.5C warmer than before the Industrial Revolution. A Unep report estimated the 2035 plans would allow the Earth to warm by between 2.3C and 2.5C. The projection has slightly improved from earlier forecasts of between 2.6C and 2.8C.

Antonio Guterres, the UN secretary-general, said the 2035 targets represented progress but were nowhere near enough, warning: “Current commitments still point to climate breakdown.” Guterres said the Cop30 meeting “must be the turning point” but insisted it was still possible to hold warming to 1.5C.