This study found that hospitalised COVID-19 patients had an incidence rate of 35 per 1,000 person-years for experiencing at least one cardiovascular event following the SARS-CoV-2 test. Additionally, having pre-existing cardiovascular risk was associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events post-COVID-19, while vaccination against COVID-19 before the SARS-CoV-2 infection decreased the risk of cardiovascular events.

Several studies have explored the occurrence of cardiovascular events after COVID-19, although not all have provided estimates of their incidence rates. As mentioned, we estimated an incidence rate of 35 per 1,000 person-years for at least one cardiovascular event. However, this estimate varies considerably across studies, ranging from 2 to 126 per 1,000 person-years [34, 35]. Such heterogeneity persists even when considering prevalence estimates. We estimated a prevalence of 8% for at least one cardiovascular event, which also varied in the literature between 5 and 31% [34, 36]. Discrepancies in these figures may stem from differing composite outcomes evaluated across studies. While our study examined a spectrum of eight cardiovascular events, most studies focused on fewer events. However, even when considering individual cardiovascular events, we observed similar heterogeneity. Few studies have specifically examined incidence rates. To the best of our knowledge, estimates were only available for acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke [24, 35]. Our findings indicated an incidence of 31 per 1,000 person-years for ischemic stroke. Notably, this rate was substantially higher than previously reported, 4.5 per 100,000 person-years [35]. Considering individual events, we found a prevalence of 0.06% for myocarditis and 1% for ischemic stroke after COVID-19, which was higher than the 0.02% and 0.4% reported, respectively [24]. In contrast, we found a lower prevalence of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis than the pooled prevalence reported in a meta-analysis (0.8% vs 1.2% and 0.2% vs 2.3%, respectively) [24]. Heterogeneity in outcome definition, different study designs, sample sizes, and follow-up periods challenge comparison and explain some of the differences reported.

However, despite variations in reported estimates, numerous studies have consistently found a higher incidence and/or risk of cardiovascular events among individuals hospitalised with COVID-19 compared to control groups. For instance, individuals hospitalised with COVID-19 have been shown to have a higher risk of ischemic stroke compared to those hospitalised for other reasons [37]. A higher risk of ischemic stroke, arrhythmia, myocarditis, heart failure, and thromboembolic disorders was also reported in hospitalised COVID-19 patients compared to individuals without COVID-19 [17, 24, 38]. However, comparing these findings is challenging due to differences in control group selection. Individuals hospitalised with non-COVID-19 conditions may differ from those who test negative for SARS-CoV-2, potentially having a different clinical background with more comorbidities. Control groups should be carefully selected to estimate accurately the risk of cardiovascular events following COVID-19 hospitalisation and ensure comparability in background risk factors. Wang et al. matched controls to cases on several variables, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities, among others [17]. Using matched control groups and considering potential confounders are essential to reducing bias and ensuring consistent comparisons. Due to resource limitations and ethical clearance, we were unable to use data from a control group. We compared the prevalences estimated in this study with those reported in Portugal. Our research indicates that the prevalence rates identified align closely with documented rates in the Portuguese population for certain cardiovascular events. We found a slightly higher prevalence of heart failure within our cohort compared to the general population (4% vs. 3%) [39]. Similar prevalences were found for deep vein thrombosis, and lower prevalences were observed for acute myocardial infarction (1.05% vs 3.2%), arrhythmia (1.94% vs 9%) and stroke (1% vs 1.6%) [40]. Thus, further studies in Portugal should explore whether cardiovascular events post-COVID-19 are indeed more frequent in individuals hospitalised with COVID-19.

Nonetheless, there are several possible biological mechanisms for the increased occurrence of adverse cardiovascular effects in post-COVID patients, which warrant research in this area. These patients might face increased cardiovascular issues due to COVID-19-induced inflammation damaging the cardiovascular system. Direct virus binding to ACE-2 receptors disrupts cardiac function, while inflammatory pathways exacerbate circulation problems and may potentially lead to plaque rupture [41,42,43]. Maladaptive responses, including heightened autoimmune reactions, persist beyond the acute phase. Delayed cardiovascular events may stem from lingering viral reservoirs in the heart, worsened by existing risk factors [44,45,46,47]. Although further research is required for confirmation, it is vital to understand who the individuals suffering from these cardiovascular events are.

Several factors have been identified as contributing to the increased risk of PCC. Our study, consistent with findings from Roubinian et al. [48] and Kim et al. [35], demonstrated a lower incidence of cardiovascular events among participants partially vaccinated against COVID-19 compared to unvaccinated individuals. Roubinian et al. [48] observed a higher risk and prevalence of post-hospital venous thromboembolism in unvaccinated COVID-19 patients compared to those vaccinated, while Kim et al. [35] reported higher rates of acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke in unvaccinated patients compared to fully vaccinated individuals [35, 48]. While the research investigating the impact of vaccination on severe cardiovascular events during the post-acute phase of COVID-19 remains limited, a recent review identified key conclusions regarding the interplay between vaccination status and post-acute COVID-19 symptoms [49]. These include the protective effect of pre-infection vaccination against developing post-acute COVID-19 symptoms, the potential benefit of post-infection vaccination administered close to infection, and the reduction of symptoms and promotion of remission with post-infection and post-establishment of COVID-19 symptom vaccination. Nevertheless, further investigation is imperative to ascertain whether these observed impacts also extend to cardiovascular outcomes during the post-acute phase of COVID-19.

We also found that individuals with cardiovascular risk factors were at higher risk of cardiovascular events post-COVID-19, which is in line with results found in other studies [17, 18, 50]. A high proportion of our sample had pre-existing cardiovascular risk, which already increased their risk of a cardiovascular event regardless of COVID-19 hospitalisation. Nevertheless, other studies have adjusted or filtered by cardiovascular risk and still found an increased risk of post-COVID-19 cardiovascular events [17, 50]. Additionally, we also found an increased incidence of cardiovascular events post-COVID-19 among individuals with hypertension, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and ischemic heart disease. Thus, these findings underscore the importance of identifying and closely monitoring individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, as they are at higher risk of experiencing cardiovascular events following COVID-19 infection.

We did not find significant differences in the incidence rate of experiencing at least one cardiovascular event based on the severity of hospitalisation. Xie et al. [18] obtained different results, showing that the risk of developing cardiovascular complications post-COVID infection increased gradually according to the care setting, during the acute phase (non-hospitalised, hospitalised, and admitted to intensive care). However, Lee et al. [37] did not find differences between individuals hospitalised with COVID-19 and individuals hospitalised with non-COVID-19. Therefore, although studies indicate differences in PCC prevalence between hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients [21, 24, 38, 51], it is essential to explore the effect of severity further and understand whether this phenomenon is characteristic of COVID-19 infection or respiratory infections in general.

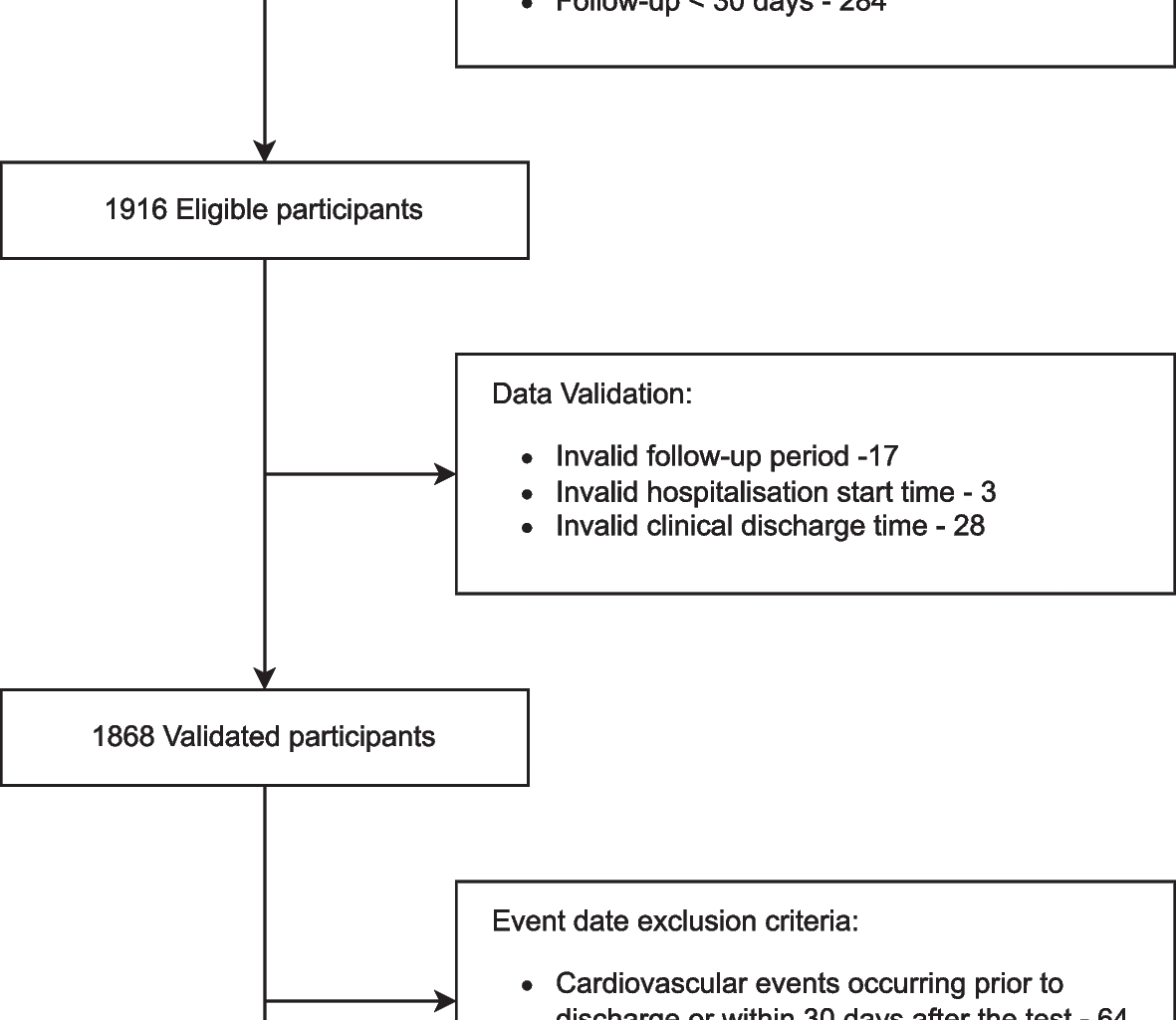

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, we extracted information about several cardiovascular events and synthesised them into a composite outcome representing at least one cardiovascular event. Despite estimating the incidence of each cardiovascular event, the use of diverse composite outcomes in the literature challenges comparison and interpretation. Additionally, our approach to identifying cardiovascular events relied on data extracted from clinical processes rather than solely on ICD-10 codes. While we provided a manual to guide clinical staff in data extraction, describing how each question should be answered, the involvement of different hospitals and medical staff introduced potential subjectivity into the process, thereby impacting the consistency and reliability of our analysis. Additionally, information bias might also be present. Although medical staff involved in data collection received training and had a data collection manual available, they had access to the entire patient clinical record, which might unconsciously influence how they recorded or interpreted the data due to prior knowledge of the patient’s history, conditions, or risk factors. Furthermore, our analysis only considered the information available in the clinical records, potentially leading to underestimating cardiovascular event incidences. This could occur if clinicians did not prioritise documenting cardiovascular events or if patients failed to report relevant clinical information, disregarding certain health conditions or events. The lack of a clear control group is a major limitation, as we are unable to ascertain whether the incidence of cardiovascular events is higher than the one reported by the general population or individuals hospitalised with other respiratory conditions. Similarly, we examined cardiovascular events following SARS-CoV-2 testing, but we cannot definitively attribute causality to COVID-19, as these events may have occurred independently. Additionally, individuals in our cohort were hospitalised at the beginning of the pandemic, when vaccines might not have been widely available for everyone. Moreover, studies have shown that vaccination after infection also decreased the odds of PCC. Additionally, with the appearance of self-testing, we cannot guarantee that individuals were COVID-19 free during follow-up, which might bias our estimates. Thus, caution should be used when interpreting our results.

Considerable attention has been focused on addressing the challenges individuals face with PCC. We extracted data from clinical records across major hospitals nationwide to assess the incidence and risk factors associated with cardiovascular outcomes for up to 16 months following a positive SARS-CoV-2 test among hospitalised individuals. Due to the heterogeneity in incidence rates of cardiovascular events post-COVID-19, it is crucial to design comparable studies and standardise outcomes for effective comparison. Furthermore, to thoroughly evaluate the impact of COVID-19 infection on cardiovascular complications, there is an urgent need for updated and broader studies examining the incidence of cardiovascular diseases. Current studies should delve deeper into the incidence rates of cardiovascular events by considering various groups and employing matching techniques to mitigate bias. Despite the need for additional research to fully comprehend the complexities of post-COVID cardiovascular events, our study reinforces the existing evidence indicating a heightened risk for individuals hospitalised with COVID-19. The risk of cardiovascular events post-COVID-19 was still evident, even with a longer follow-up (median of 18 months vs 12 months [17, 18, 20]). This risk is particularly accentuated in those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, reinforcing the need to identify individuals at current risk of cardiovascular events post-COVID-19. In particular, we found a higher incidence rate for those with hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and atrial fibrillation, diseases which are not usually under study. Given these findings, it is imperative for health systems to proactively organise and implement screening protocols for individuals who were hospitalised with COVID-19 and with pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors. By identifying and closely monitoring these patients, healthcare providers can intervene early to mitigate the risk of post-cardiovascular events. This proactive approach can significantly improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden on healthcare resources by preventing or minimising the severity of cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19.