In response to the publication of ten research priorities related to the cause, diagnosis, management, and treatment of PA by the JLA-PSP, our study sought to establish a PA research repository. This repository is designed to promote and facilitate research that addresses these critical questions. Our study has begun to identify trends and associations that can help form hypotheses and guide future lines of research.

A wide range of age-of-onset is reported for PA

Generally, for diseases, the younger the age of onset, the more important the role of common environmental and/or heritable factors. Conversely, the later the age of onset, the more prominent the unique environmental factors for the individual are [19]. We used ‘age of diagnosis’ as a rough proxy for ‘age-of-onset’ in participants and observed a near-normal distribution. The findings challenged the commonly held perception that PA primarily affects older adults [4].

Exploring the aetiology of PA

Our study participants were predominantly female (81% with female to male ratio of 4:1). This reflects the known gender imbalance in PAS membership (85% female) [20] but also the higher prevalence of autoimmune conditions among females [14, 21,22,23,24].

We stratified our participants into two groups – sporadic and familial – hypothesising that different types of PA may exist. Our results suggest significant familial clustering and notably higher than rates (approximately 33% versus 20%) previously reported [25]. It is important to note that, whilst most participants identified no known familial link for their PA, this is likely partly due to a high rate of under/misdiagnosis associated with the condition [5]. The identification of families with multiple members with PA or other AIDs paves the way forward for future studies investigating the role of rare and common genetic variants associated with susceptibility and prognosis of PA. Furthermore, sporadic and familial forms of many other multifactorial diseases exist, and the observations reported here for PA are consistent with this [26, 27].

Multimorbidity in PA participants

Multimorbidity, defined as the presence of two or more chronic conditions, was prevalent among the participants; half reported having one or more autoimmune diseases or other comorbid conditions [28]. Additionally, although not specifically detailed in this paper, cases of complex multimorbidity involving three or more conditions affecting at least three different body systems were observed. This distinction is crucial as the management of patients with PA alone should differ significantly from those with multiple chronic conditions, such as other AIDs. Appropriate management of these coexisting conditions is essential, as mismanagement could exacerbate symptomology, leading patients to believe they require more frequent B12 treatment when, in fact, better management of their other conditions might be needed.

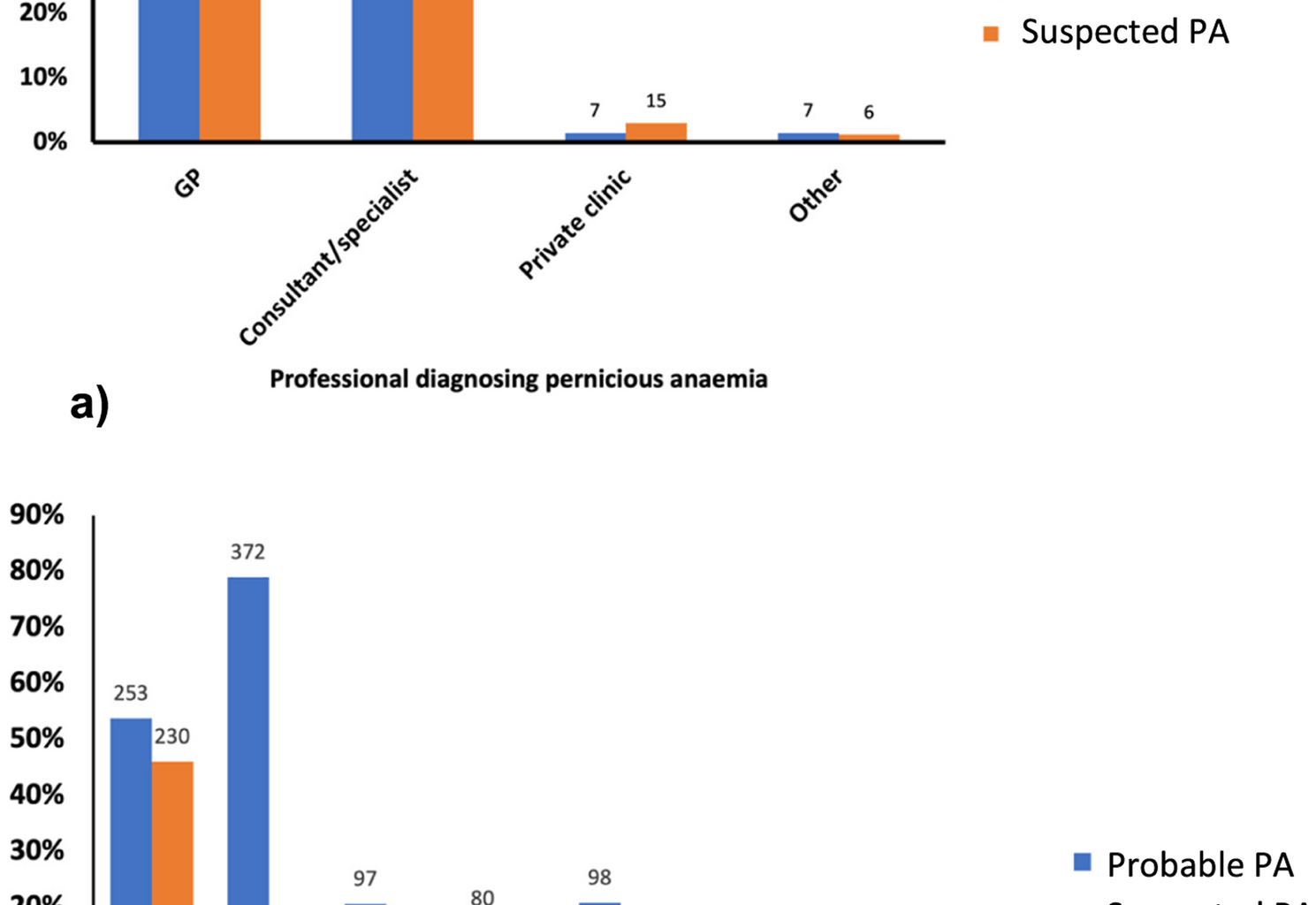

Diagnostic groupings

The diagnostic groupings were created and assessed to determine any impact of diagnosis method on presentation. Interestingly, no major differences were found between these groups, except for higher iron deficiency in the probable PA group. This suggests that, phenotypically, the individuals present similarly regardless of diagnostic criteria. Even in the ‘no diagnosis’ group, the presentation of the condition was broadly similar, in terms of demographics, comorbidities, and micronutrient deficiencies, suggesting that individuals in this group may in fact have undiagnosed PA. However, it is important to consider that not all participants may have PA. They may have B12 malabsorption due to other gastrointestinal issues, such as conditions like coeliac disease and Crohn’s disease or the use of medications like proton pump inhibitors [29]. Due to these diagnostic limitations, some individuals may be categorised as requiring B12 injections but not truly having PA.

What might be causing diagnostic delays in PA?

Undoubtedly, as shown by our survey, obtaining a confirmed diagnosis of PA presents a significant challenge to patients. This is partly due to diagnostic challenges, including inadequate testing protocols and lack of a ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis. There is also a lack of awareness of PA among primary and secondary care practitioners [30,31,32]. Our survey highlights considerable variability in the diagnostic tests administered. Most participants were diagnosed solely through assessment of serum B12 levels, despite recognised concerns about the sensitivity and specificity of this test [33].

Due to the diagnostic limitations, a significant proportion of individuals in the ‘no PA diagnosis’ group likely have ‘undetected’ PA, given that most need regular B12 injections to relieve their symptoms. The absence of the Schilling test means that individuals are currently diagnosed either through assessment of serum B12, B12 metabolic markers (MMA or tHcy), or detection of IF or PC autoantibodies, but rarely with gastroscopic confirmation [18, 34].

The absence of a universally accepted ‘gold standard’ for accurately diagnosing PA poses a significant obstacle to optimising patient management and presents a substantial challenge for research in this field. While PCA and IFA tests are useful tools in the diagnostic workup of PA, both have important limitations. IFAs are highly specific (>95%) but have low sensitivity, being absent in over half of PA cases [35]. PCAs are more sensitive but less specific and may also be present in other autoimmune conditions [36, 37]. As such, PCA testing may be used as a screening tool to guide further investigations, including IFA testing. These limitations, alongside variability in testing practices across UK laboratories, underscore the diagnostic challenges in confirming PA through serological testing alone.

Several articles propose diagnostic criteria based on various tests for PA diagnosis but often lack specific or robust guidelines that describe a pathway or algorithm that clinicians can use to guide them [38, 39]. Other diagnostic algorithms to guide clinicians exist, yet they incorporate tests with poor sensitivity, such as the IFA test, or lack endoscopic testing [33, 40]. Furthermore, these algorithms often require the presence of objective parameters like anaemia, glossitis and a low serum B12, which will not be present in many true PA cases.

Since PA is defined by the advanced and end stages of autoimmune atrophic gastritis, gastroscopy, which allows for assessing gastric mucosal changes and sampling for diagnosing autoimmune atrophic gastric using the universal Sydney classification, is particularly important [41]. However, very few of our participants report being offered a gastroscopy. To support a more accurate PA diagnosis pipeline, gastroscopy should be routinely carried out with appropriate sampling techniques of the antral and corpus for histology testing, particularly in cases where there is clinical suspicion of PA but IFAs are negative [42]. Dottori et al. highlight that serum biomarkers such as pepsinogen, gastrin, PCA, and IFA can be used in combination as a ‘serum biopsy’ panel to help identify patients with high suspicion for autoimmune gastritis and PA who should be referred for gastroscopy with biopsies [39].

Timely diagnosis is critical in PA; the duration of symptoms influences symptom type, severity, and recovery [43]. Delaying B12 treatment for a prolonged period can result in irreversible neurological damage and permanent symptoms [38, 44, 45]. Vague and non-specific symptoms – due in part to autoimmune co-morbidities that present with similar symptoms – and limitations of tests, often exacerbated by lack of training and education [46], also contribute to misdiagnoses [31]. If there is a suspicion of PA but a diagnosis has not been reached, and other possible causes of the clinical presentation have been explored, it is important to trial B12 treatment and carefully monitor improvements in symptoms to assess the clinical picture.

Our findings further highlight that delays in patients receiving a diagnosis and commencing treatment play an important role in driving requirements for more frequent B12 injections to manage their symptoms effectively. Future guidelines and clinical practice are likely to benefit from incorporating this factor into decisions about treatment frequency, recognising that individuals with longer diagnostic delays may have greater symptom burden and treatment needs.

A need for a more tailored vitamin B12 treatment regimen

The varied treatment frequencies observed strongly support the need for a more tailored approach to the management of PA, which goes beyond more frequent B12 injections [11]. The underlying basis for these different requirements remains unknown and warrants investigation. One clear finding is the widespread dissatisfaction among respondents, with many continuing to experience B12 deficiency-related symptoms when following current recommended guidelines [47]. It is important to highlight that the evidence to support current guidelines is poor, based on theoretical calculations on average B12 excretion in the urine [48].

Biomarkers of B12, including serum B12 and MMA, are of limited value in monitoring response or as a basis for prescribing a particular injection frequency [49]. Improved symptom monitoring and discovery of novel “response” biomarkers are, therefore, key targets for research. It will be critical to achieve tailored treatment regimens that lead to optimum symptom management and improved quality of life and prognosis for PA patients.

More than half of the participants reported receiving B12 injections outside of the recommended guidelines, which is likely under-reported. Anecdotal evidence suggests that recent treatment initiation, reluctance to self-inject, and financial constraints may all contribute to why more individuals are not seeking more frequent injections. A 2014 survey of PAS members reported that 13% of participants injected outside guidelines [14]. This perhaps indicates a potential shift in accessibility, knowledge and empowerment, or practitioner engagement. In the absence of objective PA biomarkers that correlate with patient symptoms, we support the principle that treatment decisions should be guided by patient-reported symptoms and signs assessed by the clinician, with individualised care prescribed based on clinical response and patient needs.

Should we recognise sub-types of PA?

We have already highlighted that, from a purely genetic perspective, there may be at least two sub-types of PA – which we named sporadic and familial. We can also begin to formulate other ways to classify PA. From our survey and previous studies, we know that approximately 50% of PA patients present with other AID comorbidities, including vitiligo and autoimmune thyroid disease (Graves’ & Hashimoto’s), whilst in 50% of individuals, PA remains their only diagnosis.

The mechanisms of association between PA and other AIDs are unknown. The life course of PA allows stratification of the disease into those factors occurring prior to diagnosis (e.g., including Helicobacter pylori infection) or those associated as a consequence and life-course of the disease itself (i.e. iron, vitamin D or folate deficiency). Finally, we can also clearly describe sub-types of the disease based on treatment (type, mode) requirements. Follow-up studies using the proposed repository described here will aid the identification of other factors that could be used to stratify PA into different sub-types, contributing towards a new ‘precision medicine’ approach to future PA diagnosis and management.

Proposed objectives of the PAS research repository

The primary objective is to support research aligned with JLA PSP priorities in PA and recent NICE guidelines [17]. Additionally, we aim to enhance participant recruitment through strategies developed with healthcare institutions and patient advocacy groups, focusing on integrating datasets from diverse sources into current and future studies. We also plan to facilitate medical records review and harmonise metadata from established biobanks, working with healthcare providers to securely access detailed medical histories, diagnoses, and treatment information. Finally, we will establish protocols for the collection, processing, and storage of biological samples (blood, urine, DNA/RNA), ensuring informed consent and addressing ethical considerations in collaboration with healthcare facilities.

New research to improve our understanding of the range of symptoms experienced by individuals with PA and their varying responses to treatment is urgently needed. The development of objective biomarkers to assess treatment response and to better understand why some individuals require more frequent B12 injections could address up to 7 out of the 10 questions of the JLA-PSP. The exploration of multi-omics-based technologies, including metabolomics and proteomics, the utility of wearables (smart-watches), and neurological tracking markers as tools to identify novel markers that objectively assess symptomology and response to treatment in PA, should be considered as priority aims [50, 51].

Guidelines for researchers wanting to use the repository to tackle JLA questions

To facilitate research inquiries and collaborations utilising the PA Research Repository, we are in the process of forming an executive committee, comprised of representatives from the PAS committee, cluB-12 committee, researchers from the University of Surrey, and patients. Researchers interested in accessing the repository for studies aligned with the JLA research priorities or other related topics are encouraged to initiate contact through the corresponding author of this manuscript in the first instance.

Strengths and limitations

The PAS research repository offers a unique resource with the potential to facilitate research, advance knowledge, and improve patient quality of life. The screening survey has provided valuable initial data and identified a willing cohort for future studies. However, there are several limitations to consider.

Firstly, the data is self-reported. While members of this patient group are highly engaged and knowledgeable about their condition, there is still the potential to introduce a degree of recall bias. Furthermore, participants were exclusively recruited from PAS, which will also introduce selection bias, making the results not fully representative of the broader PA population. This selective recruitment could indicate a higher motivation to manage their condition, potentially reflecting a more severe disease profile, dissatisfaction, or higher socioeconomic and educational status [52]. While the participant group is geographically representative of the UK (participants are predominantly UK-based), negative experiences may bias the dataset. However, this cohort includes individuals reporting high satisfaction with their treatment regimen despite their involvement and willingness to participate in research.

Some predictors in the regression analysis must be interpreted cautiously. Age at diagnosis was used as a rough proxy for age of onset, given the lack of a gold standard for diagnosis and the absence of a biomarker to determine onset. However, we recognise this will overestimate the true age of onset due to diagnostic delays. Similarly, treatment satisfaction was measured only in relation to healthcare professional–provided care; individuals who self-source injections may appear less satisfied with official NHS provision but remain satisfied with their overall symptom management.

Additionally, the absence of an independent, clinician-diagnosed group as well as a non-PA control group limits our ability to contextualise the prevalence of co-occurring conditions such as vitamin deficiencies or other comorbidities. Future studies by us and others should explore and validate our findings using appropriate comparison cohorts. More detailed diagnostic test results are also needed, particularly for individuals without a formal diagnosis. We also currently lack access to participants’ medical records, which limits our ability to validate diagnoses or explore diagnostic test results in detail. Future research will prioritise linkage with primary care data and direct recruitment from healthcare settings, allowing for validation of self-reported outcomes and further investigation of diagnostic pathways and treatment efficacy. We aim to further investigate and characterise individuals without a confirmed diagnosis, as their results suggest they underwent insufficient testing. This work will contribute to a better understanding of PA diagnosis.