The gradual retreat from ambitious climate action among some politicians and companies, emboldened by climate change-denier Donald Trump’s return to the White House, has caused alarm among advocates for the green energy transition.

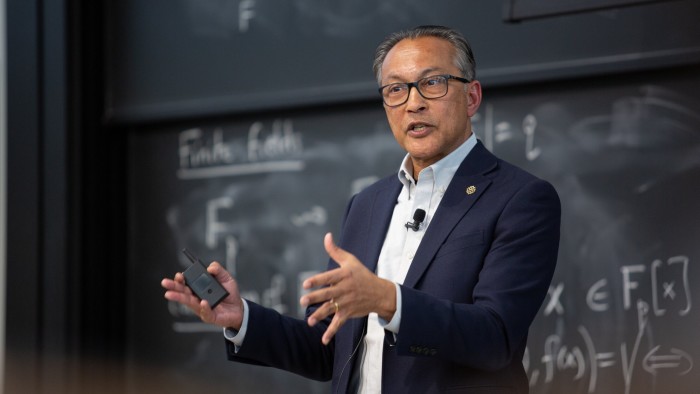

Yet Ani Dasgupta, president of the World Resources Institute (WRI), one of world’s largest environmental think-tanks, refuses to give in to the pessimism of some of his peers. “We should be shocked and horrified at the moment we find ourselves in,” he concedes. But he sees the backlash against the shift away from fossil fuels towards clean energy as limited to rich countries.

In large middle-income countries it is a different story. The focus in Jakarta, New Delhi, Beijing or Nairobi, he says, is: “How much faster can we do this? Why isn’t private capital coming to invest in renewables? The tone of their problems is completely different.”

Dasgupta, who joined the WRI in 2014 after nearly two decades at the World Bank, has found that his views often set him apart from his colleagues. His recent book, The New Global Possible: Rebuilding Optimism in the Age of Climate Crisis, sets out how he believes the world can continue moving forward with the transition, even if it means activists have to swallow some unpalatable ideas.

Recommended

“Lots of my colleagues are not happy with my chapter on business,” says Dasgupta. He believes there are limits to what companies will do voluntarily with regard to climate action, and that more regulation is needed.

Yet the WRI is one of the organisations behind voluntary climate schemes such as the Science Based Targets initiative, which influences how companies can credibly claim they are on track for net zero.

Most consumer-facing companies have plans to reduce emissions for the sake of their reputation and to comply with EU policies, for example. However, businesses “won’t do the hard things” unless they have to, he says.

Since Trump began his second term as US president, a slew of companies have left voluntary corporate climate initiatives. In October, the Net-Zero Banking Alliance officially ceased operations after banks voted to shift from a membership-based structure to a guidance framework. Companies joined in the “euphoria of Paris”, says Dasgupta. “I don’t think they knew what they were signing up to or how hard it is to decarbonise, especially if you are a multinational with long value chains across the world.”

Another failure has been the lack of focus on finding a path for companies to be profitable while decarbonising, he says. “You can’t expect a company to not make profit and be good for carbon, as it won’t exist in a commercial sense.”

In his book he uses Ikea as an example to show how it is possible for emission reductions and profit to go hand in hand. In 2024, the flat-pack retailer’s emissions were over 30 per cent lower and revenues were up nearly 24 per cent compared to a 2016 baseline.

In addition to the momentum in middle-income countries, technology — which is “delivering more than [the] Paris [agreement] imagined” — is another reason for Dasgupta’s optimism. He cites the speed at which solar, wind, electric vehicles and batteries are being rolled out, although “technology itself doesn’t deliver outcomes”, he warns. “Just producing renewables is not good enough or even not good at all. A lot of renewable energy is not being used, because we don’t have the infrastructure to deliver it.”

Recommended

This missing bit of the puzzle is what Dasgupta calls the “orchestration”. He hopes his book will help fill such gaps by focusing on the practicalities of how to take action and by emphasising what the benefits are for people.

Dasgupta says the stories in his book show climate action is only long-lasting when people can see a positive impact. He gives the example of Bangladesh, which spends a significant 10 per cent of its budget on climate adaptation. There is political support for this investment because “people’s lives are getting better because of those policies”, he says.

Another area where Dasgupta is more bullish than most environmentalists is artificial intelligence. “A lot of my peers are talking about how AI will be terrible,” he says. “Our view [at the WRI] has been, how can we use this tool for good?”

For too long my community has vilified the fossil fuel industry and got nowhere

One of the questions WRI wants to examine through its recently established energy transition centre is how the huge energy demand from tech companies could be used to help, rather than hinder, the shift from fossil fuels to renewables. Dasgupta describes the current situation as “havoc”, with “everyone buying energy everywhere”, but he believes there is potential for a different outcome.

He also insists there is no choice but to engage with oil and gas companies. “For too long my community has vilified the fossil fuel industry and got nowhere,” he says, and does not buy the argument that regulation alone can take these companies out of the picture. “That is not going to happen,” he says.

Dasgupta acknowledges that Christiana Figueres, one of the architects of the 2015 Paris agreement, gave up trying to work with oil and gas companies and admits he too might fail to bring them into line. But he sees no path to a decarbonised economy without them.

Looking ahead to COP30, he says the annual UN climate summits remain relevant. “It is very popular among armchair intellectuals to say that multilateralism is broken, and COPs are failing us,” he writes in his book. The gatherings could be made more effective, he says, to ensure greater accountability and better decision-making, with “different people in the room, most importantly finance ministers”. But, he adds: “If you don’t have a COP you will invent something that looks exactly like it.”

Europe’s Climate Leaders

The FT is compiling its sixth annual list of Europe’s climate leaders. We’re looking for those companies that are making the most progress in cutting greenhouse gas emissions and remain committed to reducing their impact on the environment. For more information on how to register, click here. The deadline for entries is November 15.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here