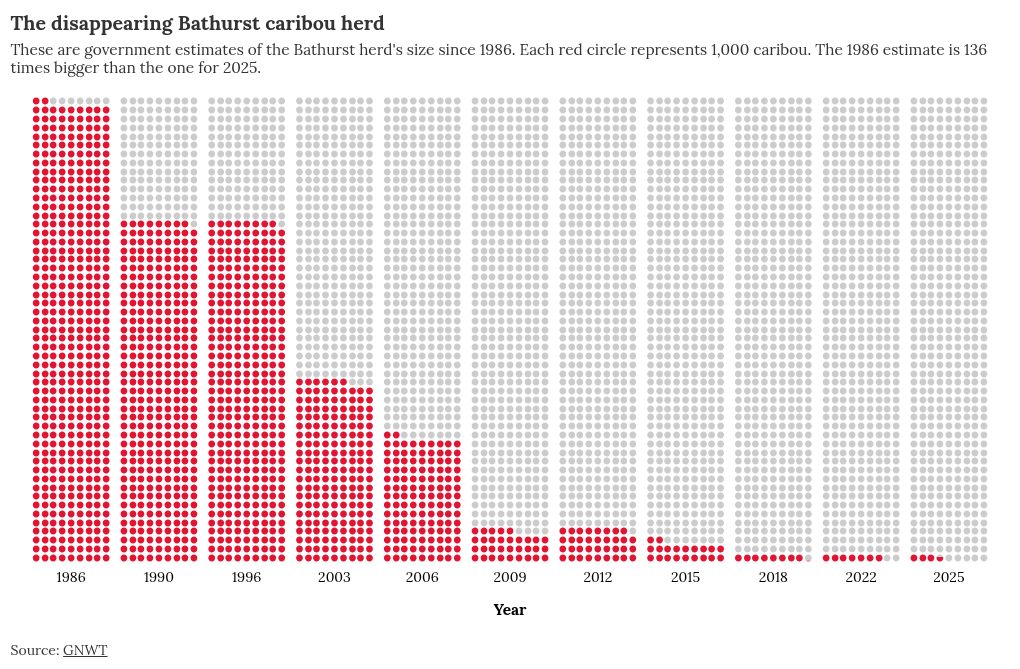

In 2022, the Bathurst caribou herd was estimated to include between 6,000 and 7,000 animals – down from 470,000 in 1986. In the three years since, the herd appears to have halved again in size.

New estimates released last week by the NWT government put the Bathurst herd at 3,609 animals, an exceedingly bleak all-time low.

That estimate represents a 47-percent drop in three years. It comes despite more than a dozen public and Indigenous governments agreeing a new plan to help the caribou in 2021.

“This decline is concerning,” the territorial government wrote in a news release, “given all the efforts of the GNWT and our co-management partners to reduce pressures on this herd.”

Authorities have struggled to articulate what, exactly, is causing the decline.

Many factors could be at work, ranging from industrial development and changes in the way caribou are hunted through to effects of climate change like an evolving habitat and the gradual northward movement of other animals and plants.

Different groups of people accept some of those factors and reject others.

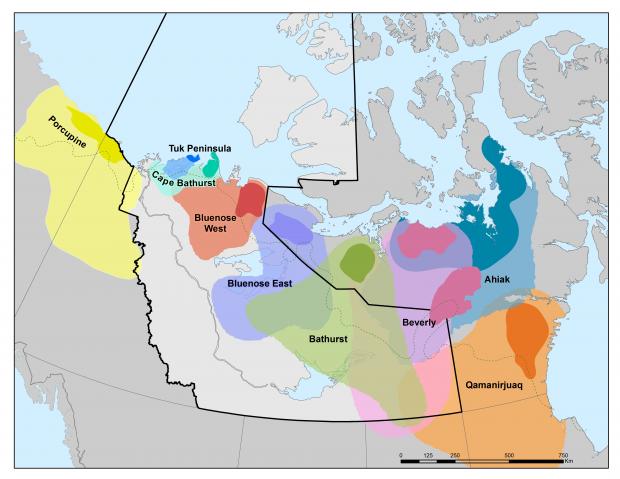

A GNWT graphic shows the estimated ranges of various northern caribou herds.

A GNWT graphic shows the estimated ranges of various northern caribou herds.

Previously, some scientists noted caribou herd sizes went up and down in cycles and suggested this might be a natural low point. Now, though, the consensus seems to be that this isn’t a point from which the herd will automatically rebound.

“In the past, it was understood that these low population phases were natural, and that caribou populations would recover over time. However, this naturally fluctuating abundance cycle appears to have been interrupted by increasing human and natural pressures,” the 2021 herd management plan asserted.

Even four years ago, the herd was thought to be at a “critically low” size. (Estimating the number of animals in a herd involves multiple counts with different techniques, a process the GNWT documents on its website.)

“Further work is ongoing” to investigate the factors behind the decreasing size of the Bathurst herd, the GNWT stated last week.

“The GNWT will meet with co-management partners over the coming weeks and months to review these results and discuss next steps to protect the herds,” the territory added.

Environment minister Jay Macdonald was quoted as saying: “Together, we are committed to strengthening conservation efforts and increase the numbers of these precious animals, tied so closely to the life in North.”

While most of Canada’s caribou herds have shrunk in recent years, only the George River herd in Labrador and northern Quebec has suffered a collapse on the same scale as the Bathurst, going from an estimated 800,000 animals in the 1990s to fewer than 10,000 now.

Of all herds, only the Porcupine herd in Yukon, Alaska and parts of the northwestern NWT is thought to be at or near an all-time high – but the United States’ move to open up drilling in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge could fundamentally alter the herd’s calving grounds.

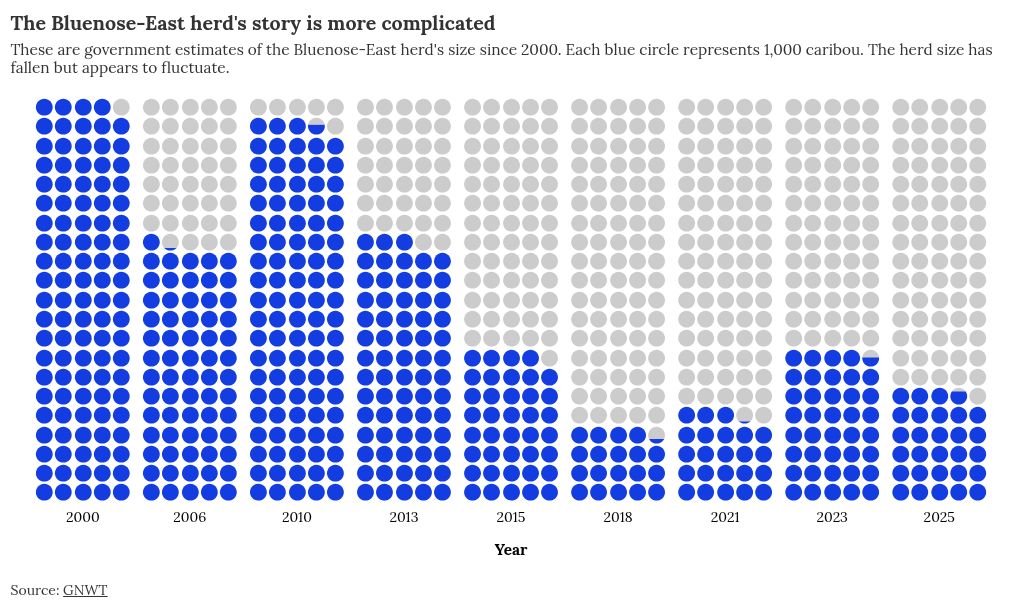

The GNWT also released new data for the Bluenose-East caribou herd last week.

While that herd’s estimated numbers have also fallen over the past quarter of a century, there appears to be more fluctuation in its fortunes.

According to the GNWT, the 2025 Bluenose-East population estimate is 28,759 adult caribou, lower than the 2023 estimate of 39,525 but higher than the 2021 estimate of 23,202.

For both the Bathurst and Bluenose-East surveys, the GNWT said conditions were good and it has a “high degree of confidence in the results.”

The latest estimates for other barren-ground caribou herds are available on the GNWT’s website.

Related Articles