A new polymer reported in Nature may mark a turning point for needle-free insulin delivery. Researchers at Zhejiang University have developed a charge-shifting polyzwitterion that can carry insulin through intact skin and into the bloodstream, producing robust glucose-lowering effects in diabetic mice and miniature pigs (Nature 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09729-x).

According to co-author Youqing Shen, transdermal delivery typically works only for small, hydrophobic molecules with masses under 500 Da. Larger molecules, including peptides, proteins, and virtually all polymers, are blocked by the dense lipid matrix of the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of skin. That barrier is so effective that cosmetic safety assessments generally exempt polymers larger than 1,000 Da from skin penetration studies, Shen says. The new study challenges that assumption by demonstrating a synthetic polymer, poly[2-(N-oxide-N,N-dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate], or OP, capable of efficiently crossing the skin and carrying insulin (~5,800 Da) along with it.

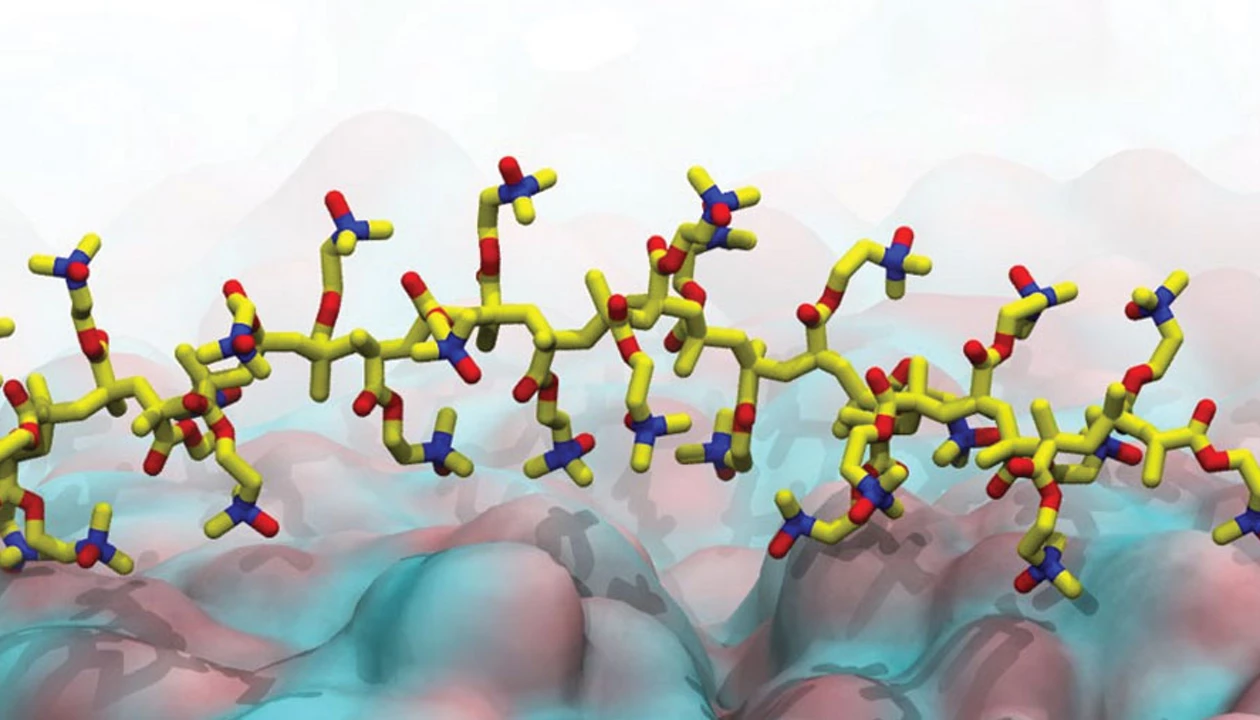

The polymer works by taking advantage of the skin’s natural shift in acidity from the surface downward. At the stratum corneum, the environment is mildly acidic, which causes some of the surface lipids to lose protons and take on a slight negative charge. OP becomes positively charged under these acidic conditions, so it is electrostatically drawn to the negatively charged lipids. This attraction helps OP latch onto and slip between the oily layers of this barrier, which normally blocks large molecules such as insulin.

A few layers deeper, where the pH becomes neutral, OP automatically switches to a zwitterionic, overall neutral state. In this form, it no longer sticks to lipids or cell surfaces, but drifts freely through the lower layers of skin and eventually circulates through the body. Insulin attached to OP follows the same route, effectively hitchhiking past a barrier it cannot cross on its own.

The researchers report that when OP was linked to insulin, it delivered enough hormone through skin to normalize blood glucose levels in small and large test animals. In mice with type 1 diabetes, topical OP–insulin produced hypoglycemic effects comparable to injected insulin. In diabetic mini pigs, a transdermal dose restored normal glucose levels without causing skin irritation or structural damage, even after repeated application.

“This work offers a significant advance, tackling a grand challenge in drug delivery,” says Matthew Webber, an engineer and specialist in supramolecular materials at the University of Notre Dame who was not involved in the study.

Shen says that the team is now working with pharmaceutical partners to advance the platform toward clinical development. Thinking beyond insulin, the researchers hope this strategy could enable transdermal delivery of other macromolecules, including therapeutic peptides and proteins such as glucagon-like peptide 1 analogs.

“A safe, noninvasive insulin delivery system could dramatically improve the daily lives of people with diabetes,” Webber says.

If the technology proves safe and effective in humans, it could offer an alternative to daily injections or patch pumps for managing diabetes and potentially open a new route for delivering drugs through intact skin. “Eliminating injections would reduce pain, fear, and treatment burden, and could make it easier for these individuals to comply with therapy,” Webber says.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2025 American Chemical Society