In June 1994 three former Beatles came together, on the neutral ground of a faceless office in Wendell Road in west London, for the first time since 1979. “Is that a vegetarian leather jacket?” Ringo Starr asked Paul McCartney. A tad defensively, McCartney pointed out that not only was his jacket vegetarian, but his shoes were too. So began the long and winding road to reconciliation.

The nervous-looking McCartney, Starr and George Harrison, with wives in tow, were meeting to discuss Anthology, an eight-part documentary, book and box set that would provide the last word on the Beatles story. There were also plans to flesh out three home recordings from the Seventies by John Lennon into Beatles songs: Free as a Bird, Real Love and, released decades later when AI technology had learnt how to eradicate background noise, Now and Then. Anthology didn’t lead to the great reunion fans had been dreaming of. How could there be a reunion without Lennon? But it was an important assessment of the band’s legacy and a healing of old wounds. Now, with a new, expanded Anthology arriving, we’re hearing how it was for the Beatles.

“It was time to find out how they felt,” says Oliver Murray, the director of a new ninth episode of the documentary, to go with remastered versions of the original eight. Murray was a teenager when the series came out in 1995 and credits it with inspiring him to make music films. “The Beatles were around for a short time. Then it’s over and they have to work out who they are as individuals, walking around as a Beatle while trying to do other things. I wanted to know: what was that like?”

Extremely traumatic, it seems. Plans for a documentary were first mooted by the Beatles’ road manager Neil Aspinall in 1971, but with the band locked in legal battles after a messy breakup, there was no way it could happen.

“Every afternoon I had to go into the Apple office to face the latest horrible development,” said McCartney when I spoke to him last year. On December 31, 1970 he had filed a lawsuit in response to Lennon, Starr and Harrison appointing the mobster-like New Jersey-born accountant Allen Klein as the Beatles’ manager. The act had brought to an end the band that had defined their lives. “It was turgid, honestly a bad, bad time. Here’s me, got into rock’n’roll to have a good time, and now I had this sluggish life, dragging my way through one mess after another.”

McCartney dealt with the problem by moving to a farm in Scotland with his American wife, Linda, and forming Wings. But the Beatles were not an entity that was going to go away. As Harrison says in a message to himself in the new episode of Anthology: “Forget about the Beatles for a while. Let the dust settle and come back to it with a fresh point of view.” The sadness is in Lennon being murdered before that could happen. It makes the scenes of the surviving Beatles, meeting once more to sit around, play ukuleles and talk about everything that happened to them, very poignant.

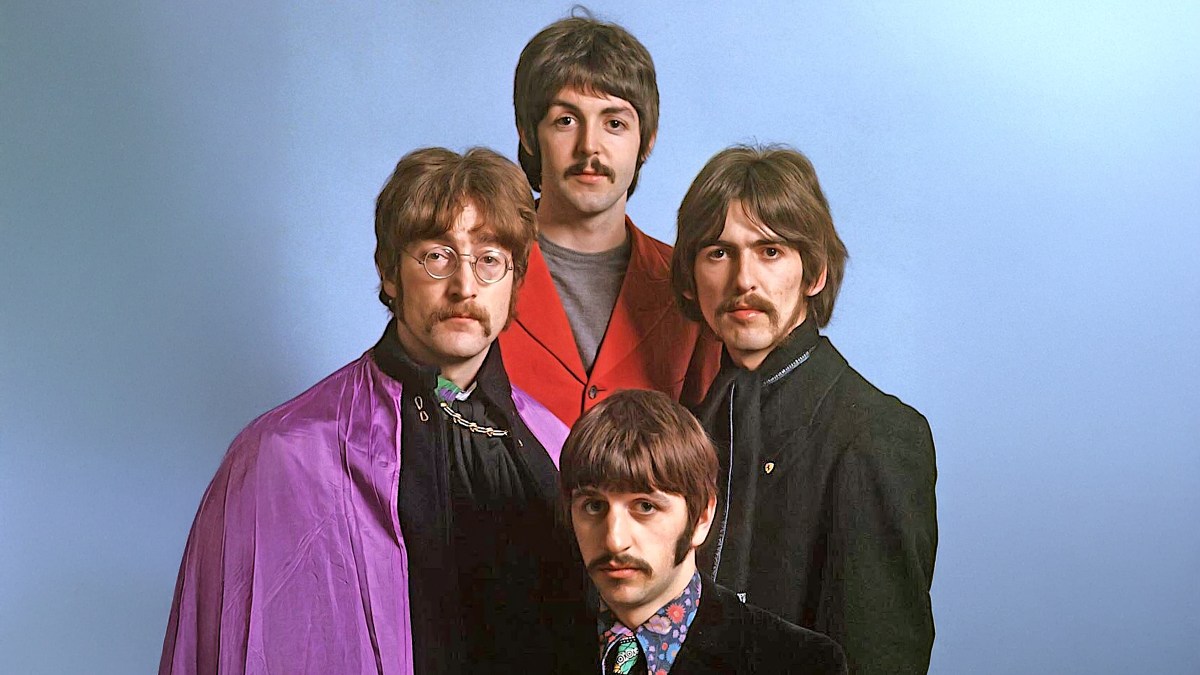

The Beatles in 1965

PAUL POPPER/POPPERFOTO/GETTY IMAGES

“We started Anthology in 1990, and the only person we spoke to was Neil Aspinall,” says Bob Smeaton, who was brought on as series director through Geoff Wonfor, a director on the original documentary who died in 2022. “Neil said, ‘This may never hit the screens, it will take as long as it takes, and there’s no budget. Just get on with it.’ So we did a rough cut from when they were kids up to the first record. Neil showed it to Paul, George, Ringo and Yoko, and a job I thought would last 12 months took over the next four years of my life.”

• Why the Beatles split up — in their own words

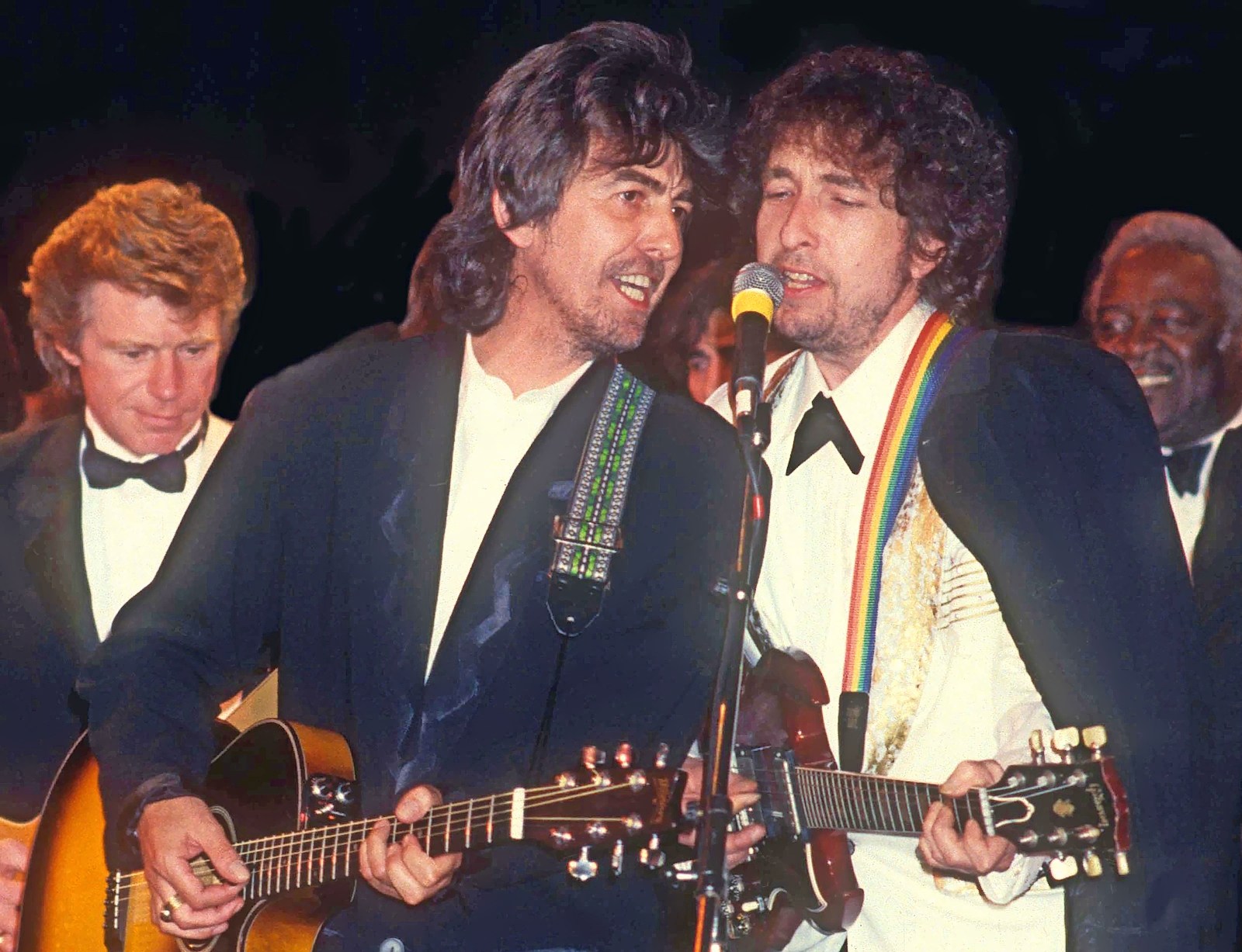

Harrison’s aversion to looking back made him an initially reluctant contributor, but severe financial difficulties with his Handmade Films company convinced him to get involved, after which he proved enthusiastic. “He’d been burned by the break-up, he’d had success with the Traveling Wilburys [a supergroup also featuring Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne] and his attitude was: ‘Why do I have to talk about this?’” Smeaton says. “But then he got into it, and he was certainly no longer the silent Beatle. When we got them into the studio at Abbey Road, it was George who took control. There was still that slight tension, and he wasn’t going to hold back.”

George Harrison and Bob Dylan performing in 1988

MEDIAPUNCH/SHUTTERSTOCK

George Martin, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and George Harrison in Abbey Road studios, 1995

DISNEY+

Smeaton says the Beatles were for the most part easy to deal with, although recollections had a tendency of deviating from historical evidence. “George absolutely refused to believe the Beatles played Shea Stadium a second time, in 1966. I showed him the footage and he still denied it! Paul told me he walked on to The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964 and played Yesterday. And I’m thinking: but you hadn’t even written it yet. How do you tell Paul McCartney he’s wrong?”

How about Yoko Ono? “Her whole thing was: ‘More John.’ She kept saying it was John’s band, he invited Paul and George in, he had a dream where he thought up the name. The others remembered the name coming from the biker gang in the Marlon Brando film The Wild One. As Neil Aspinall told me, they all saw the same things, but through their own eyes.”

• Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr: We never thought the Beatles would last

In footage shot in the garden of Harrison’s Friar Park mansion in Henley-on-Thames, McCartney is still the boss in the middle, Starr funny and cheerful to his right, Harrison a touch moody and sensitive to his left. It shows not just the coming together of the band against which all others are judged, but old friends who are warily getting to know each other again. McCartney complains about always being seen as the “work fiend”, pushing the others into doing things they didn’t want to do, to which Ringo responds: “We could just sit in the garden longer than you.” They’re still jostling for position, 24 years after the whole thing fell to pieces.

“At the end of the shoot in Friar Park, Paul and Ringo got up and walked away,” Smeaton says. “That’s when George turned to camera and said: ‘The Traveling Wilburys … now there was a band.’”

Ringo Starr with his wife Barbara Bach in 1995

JEAN-PIERRE REY/GAMMA-RAPHO/GETTY IMAGES

Murray says: “I realised they had a great source of pride in the Beatles, but also that they fell in and out of love with it. I was interested in showing how Paul, George and Ringo were trying to decide who they were under this enormous cloud of culture they created.” Or as Starr puts it: “At certain times each one of us went mad.”

We also learn that in the early days only McCartney would share a room with the new boy, Ringo; Harrison went to bed later than everyone else (“I was scared of the dark”); and their defining image came about by accident. McCartney claims that he and Lennon got their mop tops during a hitchhiking trip to Paris in September 1961, with Starr adopting the hairstyle enthusiastically when he joined in August 1962 because it covered the grey streaks at the side of his head. Beatle boots — Cuban heeled Chelsea boots from the ballet shop Anello & Davide — were taken up by the Fabs after they spotted a London-based band wearing them in Hamburg.

Then there are the unorthodox approaches to recording. On the Sgt Pepper sessions at Abbey Road, which took place when he was only 23, Harrison recalls the challenge of getting the producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick to keep working after their usual clocking-off time of 5pm.

“They would be saying, ‘Can we go home now?’ No you can’t, you bastard, have this tea,” Harrison says in the documentary . “Mal Evans [the band’s roadie/assistant] doused the tea with uppers. They don’t know to this day.”

The band in 1963

MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES/GETTY IMAGES

There is a melancholy aspect to all this, not just because of the reflections on the loss of Lennon, but also because the new version of Anthology arrives after the deaths of Harrison, in 2001, Martin, in 2016 and Emerick, in 2018. Much of episode nine focuses on the completion of those three post-break-up, post-Lennon tracks. Knowing that Ono had a cassette of some Lennon songs that never came out, McCartney asked her for permission to work on them. “And to give us a lot of freedom, not to impose rules,” he says. “I said to Yoko, ‘If you hate it, we’ll ditch it.’”

Harrison remembered it differently. He had been playing with the Traveling Wilburys when Orbison died and the idea of singing alongside a recording of Elvis Presley in his place was mooted. It never happened, but Harrison says he told Ono about the idea, and that’s when she revealed there was a tape of unrecorded Lennon songs.

• Martin Scorsese’s Beatles ’64: how the band helped to heal America

Starr claims the recording sessions for Free as a Bird, Real Love and Now and Then were “a very heavy time for me. John’s coming out of the speakers but he’s not here.” With the positivity that has got him through six decades, McCartney suggested: “Let’s pretend John’s just gone on holiday.” Then Lynne, from ELO, acting as producer, faced the challenge of getting the primitive cassette recording, stretched and filled with hisses, cleaned up in time for the others to add their parts. Somehow he managed it.

“George and I were doing harmonies and Ringo said, ‘It sounds just like the Beatles,’ McCartney recalls in the new episode of Anthology. Although of course, it wasn’t the Beatles. Without Lennon it could never be the same, which is why any offers to reunite as a three-piece were turned down. Instead the recording process gave McCartney, Harrison and Starr a chance to reunite and face up to all that had happened. It also gave Murray a chance to form an addendum to the story, not least because the footage of three Beatles working on the songs in Abbey Road has never been seen before.

“I didn’t have any direct conversations with a Beatle or their estate,” Murray says. “You get an amazing amount of freedom, and quite a lot of time, but that also means getting a lot of rope to hang yourself with. The slow feeling of dread is that if it’s not liked, if it isn’t up to the Beatles’ exacting standards, it won’t come out at all. But I had the confidence that the film would be a snapshot of a relationship that’s constantly evolving. It’s still evolving to this day.”

Starr, McCartney and Harrison photographed by Linda McCartney in 1995

© 1995 PAUL MCCARTNEY. PHOTOGRAPHER: LINDA MCCARTNEY

The original Anthology not only set the template for the long-form music documentary, it was also blessed with remarkably good timing. The Beatles fell out of fashion amid the scorched earth of punk, but by 1995 Britpop was at its height, Oasis were proclaiming a love of the Fabs to anyone who would listen and, as Smeaton puts it, “The Beatles looked good, had great songs, took the best drugs and were working-class kids. And now they were on the television while Pulp, Blur and Oasis were in the charts.”

Thirty years later, the original series has been restored and remastered, frame by frame, using technology that didn’t exist back then. “I had to work backwards, returning to the source material to restore it all. It was painstaking,” says Matt Longfellow, who edited the new cut of Anthology. “What really struck me throughout is how much more the Beatles were than the sum of their parts. And they were always good friends. Even when they fell out.”

• Read more music reviews, interviews and guides on what to listen to next

Is there anything left to say in the Beatles story? Anthology features the lion’s share of all the footage in existence, Longfellow says, from press conferences to home movies to interviews. The new box set features 13 unreleased demos, including an early version of the cheerful folk-rocker I’ve Just Seen a Face and a rehearsal for the global television broadcast of All You Need Is Love. Ultimately, though, we’re simply returning to a ten-year period when the essence of hope was distilled into four young Liverpudlians who just happened to possess the chemistry for the ideal band. As McCartney says: “Most musicians spend their lives looking for the perfect drummer, the perfect bassist, the perfect guitarist, the perfect vocalist to sing along with. I feel very privileged.”

As he might, with the new version of Anthology confirming that the Beatles continue to fascinate. “The world has changed, but the Beatles have stayed the same,” Smeaton says. “People will watch Anthology in 30 years and think: ‘Those were great days.’”

The Beatles Anthology is out on Disney+ on Nov 26; 12-LP vinyl and 8-disc CD collections are out now