New substances have been identified that would indicate ongoing chemical (or biochemical) activity in the ocean of Enceladus, Saturn’s icy moon.

A group of researchers sifted through the data collected during one of the most daring flybys of the Cassini probe: a very rapid passage just 21 kilometers from the surface of Enceladus, Saturn’s icy moon, through a cloud of tiny grains of ice expelled from its underground ocean.

Is there life? From that foray, a new analysis now reveals something extraordinary: never-before-seen organic compounds in plumes spewing from fractures in the moon’s icy shell. In addition to the molecules already known, scientists have identified a number of new substances that may indicate chemical — or even biochemical — activity taking place deep in Enceladus’ ocean.

Published on Nature Astronomythe findings mark a crucial step toward confirming the existence of active organic chemistry beneath the surface of the moon, a type of process capable of generating molecules critical to life as we know it on Earth.

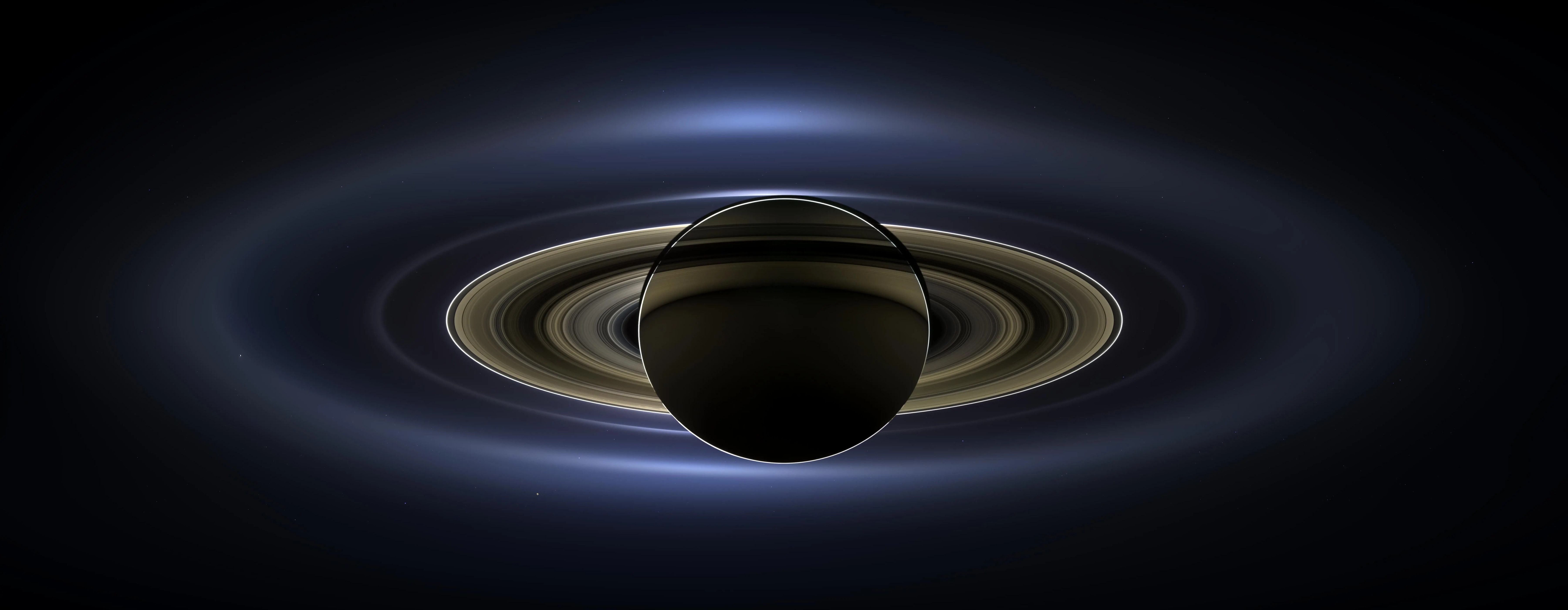

Organic molecules. Until now, scientists had been able to analyze organic compounds preserved in the grains of the E ring (the planet has seven main ones classified from A to G and various others) of Saturn, often altered by space radiation. But this time the researchers were able to study “fresh” particles, ejected from the ocean just minutes before impact with Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer instrument.

“We had previously identified organic compounds in years-old grains, potentially modified by the harsh space environment,” explains Nozair Khawaja of Freie Universität Berlin, lead author of the study. «These new compounds, however, come directly from the ocean of Enceladus and were analyzed practically as soon as they were formed». Co-author Frank Postberg, also from Freie Universität Berlin, emphasizes that the discovery confirms that the complex organic molecules found in the E ring “are not simply the result of long exposure to space, but are indeed present in the moon’s ocean.”

The impact. The credit goes above all to the flyby in 2008, when the probe – launched at over 18 kilometers per second – passed through a plume of ice and steam. The impact shattered the grains into a cloud of fragments and ions that his mass spectrometer could analyze with great precision.

Scientists were thus able to examine tiny particles, smaller than a flu virus, and identify organic compounds never seen before in Enceladus’ plumes: esters, aliphatic and cyclic ethers, some with double bonds in their structure.

Molecules which, together with the aromatic ones containing nitrogen and oxygen already confirmed, could constitute the building blocks for more complex chemical reactions, of great interest for astrobiology.

The search for life. The findings strengthen the idea that Enceladus’ ocean is not just a reservoir of liquid water, but a dynamic environment where advanced organic chemistry may be present. In short, a context that could significantly narrow the field of research for life forms in the solar system.

After that flyby, Cassini — operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory — continued to explore Saturn and its moons for nearly a decade, leaving us a wealth of data.