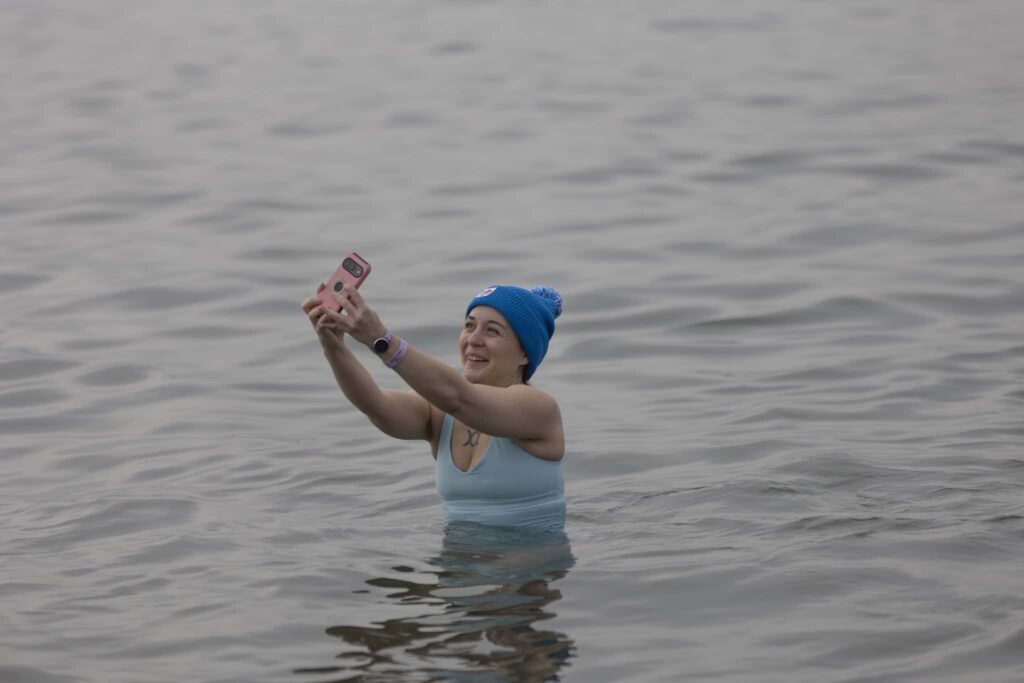

“For me, swimming is all about freedom and weightlessness,” says Ella Foote, editor of Outdoor Swimming Magazine, the world’s only print publication dedicated entirely to open-water swimming.

Foote is passionate about swimming outdoors, especially in the United Kingdom’s chilly waters.“Winter can feel dull and lifeless here,” she admits. “But since I’ve started swimming outside year-round, I see it differently. It’s become a way to connect with nature, even in the cold.”

Throughout the cold months, Ella makes a point to swim at least once a week. That consistency, she notes, makes all the difference. “It’s like going to the gym; if you go often, you start to love it. But if you only do it occasionally, you just end up wondering why anyone would.”

But what actually happens to your body when you plunge into freezing water? Why does something so unpleasant turn into such a satisfying high afterward? Turns out, there’s some real science behind that.

The Science of the Cold Plunge

“When you first jump into cold water, whether it’s a plunge, a shower, or a swim, your body experiences what’s called the cold shock response,” explains Dr. Stephen Sau-Shing Cheung, from Brock University.

“This happens when your skin temperature suddenly drops from warm to cold. It triggers your fight-or-flight response, preparing your body for action,” he told ZME Science.

Cheung notes that the sympathetic nervous system activates aggressively, flooding your body with adrenaline. It is the same kind of intense physiological arousal you would experience if you were suddenly startled or injured.

However, this response is more than just an adrenaline rush; it can be a critical, even life-threatening event, particularly for people with underlying heart conditions. From a medical perspective, your body quickly shifts to a faster heart rate, higher blood pressure, and shortness of breath.

This creates a physiological paradox known as “autonomic conflict.” The cold shock triggers a signal to accelerate the heart (tachycardia), while the ‘diving response’ sends a powerful ‘brake’ signal to slow the heart down. This conflict places the heart in an unstable state and can cause severe cardiac arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats). In rare cases, it can cause sudden cardiac death, even in young, fit, and healthy individuals.

However, in many cases, and especially for swimmers like Ella, that physiological jolt comes with mental and emotional benefits. “If I swim on a winter morning, I’m more productive, I sleep better, and I’m generally in a better mood,” she says.

What’s even more encouraging, she adds, is that you don’t have to spend long in freezing water to feel the effects. “Just a couple of minutes, two to five, really, is enough to get most of the benefits.”

But Cheung insists there isn’t any solid scientific evidence to support many of the purported long-term physiological health benefits. Furthermore, the cold plunge is very risky for the uninitiated and unhabituated.

“If you have a known heart condition or poor circulation, it’s important to be cautious,” Dr. Cheung warns. “At the very least, check with your doctor first and get a physical before trying it, because it does put stress on the heart, especially if you already have an underlying issue.”

Your Body on Cold Water

So, if there are risks, why do people like Ella report feeling so good? The answer lies in a process known as hormesis, where a low-dose, acute stressor induces beneficial, adaptive responses that enhance resilience.

For starters, repeated, controlled exposures (as few as six 3-minute immersions) can help the body mitigate these dangerous reflexes. This is called habituation. The physiological effects are profound and many of the health hazards are minimized (though not eliminated).

But what about the physiological benefits?

It turns out, many of the claims are based on relatively small-scale studies, and the scientific evidence is unclear.

For instance, observational studies note that regular swimmers report fewer infections, but this is plagued by a “healthy user bias”—it’s unclear if the swimming makes people healthy, or if only healthy people choose to do it. Cold exposure is a well-known activator of the Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT), a special “burning” tissue that generates heat by consuming glucose and lipids. Repeated exposure can turn “storage” fat into “burning” fat, but contrary to popular belief, this doesn’t always lead to fat loss.

The most robustly supported long-term benefit is the one Ella describes: a profound effect on mood. The science provides a clear neurochemical basis for this. One study examining the hormonal response to one hour of cold water immersion (at 14°C or 57°F) found a massive 530% increase in plasma noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

This massive surge probably explains why people feel so good after cold swimming. Noradrenaline is a key neurotransmitter for arousal, vigilance, and focus, producing the feeling of being “wide awake” and cognitively sharp. Dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter of the brain’s reward and motivation circuits, providing a powerful feeling of pleasure, satisfaction, and elevated mood that explains the practice’s “antidepressant effect”.

Winter Swimming Tips

The Winter Swimming World Championships in 2014. However, outdoor swimming is much more popular as an amateur activity. Image via Wiki Commons.

The Winter Swimming World Championships in 2014. However, outdoor swimming is much more popular as an amateur activity. Image via Wiki Commons.

Then, there’s also the subjective experience.

“Outdoor swimming often feels spontaneous, something you do on a sunny day,” says Ella. “Winter swimming is different. You need to plan ahead: get in, enjoy it, and get out safely.”

She emphasizes the importance of knowing your own body. “Go regularly and pay attention to how you feel. Take notes if it helps, learn what works for you. Don’t stay in too long, because of something called ‘afterdrop.’ That’s when your body keeps cooling even after you’re out. We call the first few minutes after a swim the ‘honeymoon period.’ You feel amazing and alive, but it’s actually the crucial time to get dry, put on warm clothes, and sip a hot drink before chatting with others.”

Cheung recommends never going alone. This is more than just a safety thing; it makes the entire activity more enjoyable. “Cold bathing in a social environment gives you connection, and it gets you out of the house on a chilly day. Those are some of the added benefits.”

He also issues a strong warning about alcohol: “Don’t mix alcohol with cold swimming. It dulls your sensations, so you don’t respond as well if an emergency arises, the kind of signals your body gives in cold water. Alcohol also keeps your blood vessels and skin wide open, which makes you feel warm and flushed, but it actually causes you to lose heat faster.”

Lastly, it’s always recommended to have a quick way to dry and reheat. Hot drinks are always welcome after a cold swim.

For those prepared and respectful of the risks, a cold plunge can be more than a shock. It’s an invigorating reset—one that wakes up the body, sharpens the mind, and leaves many swimmers riding a natural high for the rest of the day.