Most days you move through the world without thinking about the invisible creatures that surround you. Yet one of them, a tiny marine organism called Solarion arienae, is quietly reshaping what you know about the origins of complex life. Its discovery opened a rare window into the early evolution of eukaryotic cells and uncovered a branch of life so deep and unfamiliar that scientists had to name an entirely new phylum and supergroup to describe it.

A surprise growing in a forgotten dish

The path to Solarion began in an unexpected place. Researchers in Europe were studying a different microbe when their ciliate culture failed. What appeared to be a simple lab mishap led to a closer look inside the dish. There, tiny round cells with delicate stalks had taken over. For years these cells had slipped by unseen, too small and slow to call attention to themselves. Once isolated, though, their strange traits signaled that scientists were dealing with something rare.

Initial DNA tests could not place Solarion near any known group of eukaryotes. Newer phylogenomic tools finally revealed its closest known relative, a mysterious protist named Meteora sporadica. That link helped researchers recognize that these organisms represented not just a new species but a new phylum called Caelestes.

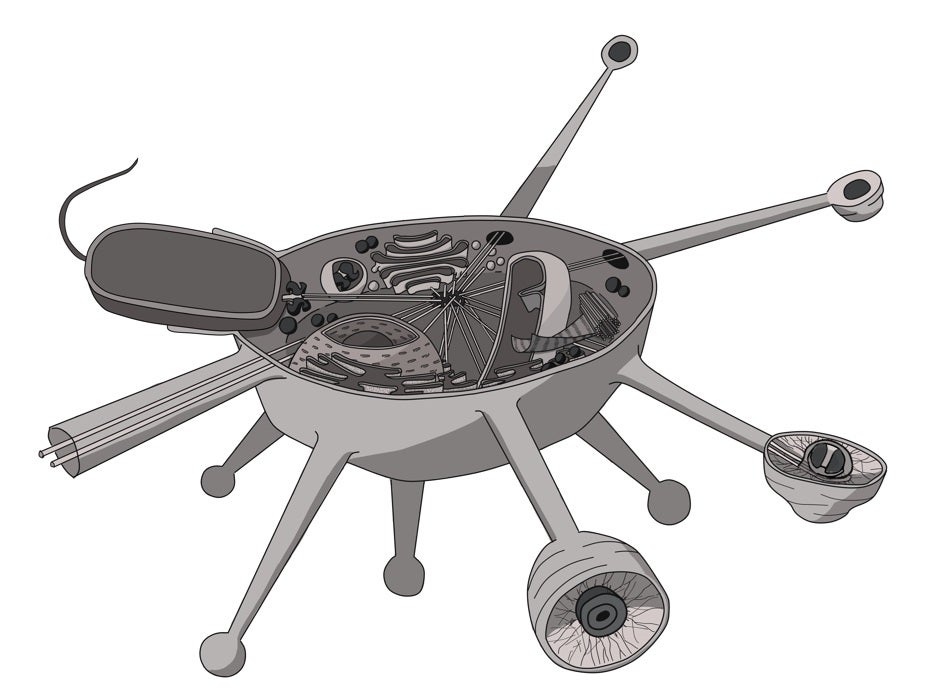

Morphology and ultrastructure of Solarion arienae. (CREDIT: Nature)

Even with improved genetic tools, this microbe barely appears in global environmental surveys. A broad search across more than 1.8 petabases of DNA and RNA sequences uncovered only scattered relatives. This suggests Solarion might be common only in very narrow habitats or part of what researchers call the “rare biosphere,” a community made up of species that live at very low numbers yet hold important evolutionary stories.

Two tiny bodies and a one of a kind hunting tool

Under the microscope, Solarion shows two forms. The most common is a small, round structure covered with stalks. Each stalk ends in a specialized weapon called a celestiosome. These sun-like cells use the celestiosomes to spear bacteria and pull them in. The second form looks more like a swimmer, with a single long flagellum and a short tail. Scientists have watched these flagellated cells shift into the sun-like shape, hinting that the two forms may be part of a larger life cycle.

Inside these cells, the structure is just as unusual. A single nucleus sits wrapped in endoplasmic reticulum. Sparse mitochondria float nearby. A double-centered cytoskeleton supports the cell, with one organizing center attached to a centriole and another free-standing deeper in the cytoplasm. The free-standing center sends microtubules outward, with several extending into the stalks that hold the celestiosomes. This mix of features sets Solarion apart from any known eukaryotic group and strengthens its link to Meteora, which also shows distinctive organizing centers.

Phylogenomic analysis: Maximum likelihood phylogenomic amino acid tree of 87 eukaryotes encompassing the breadth of known diversity, built with IQ-TREE v2 under ELM+C60+G4 model. (CREDIT: Nature) The creation of a new phylum and supergroup

The celestiosomes themselves turned out to be key to naming the new phylum Caelestes. Each of these structures has a hollow cavity and a central shaft. When triggered, the shaft fires a filament that penetrates a bacterial cell and reels it in. Because these extrusomes differ sharply from those in other protists, they serve as a defining trait for the group.

From there the findings grew even broader. Using hundreds of protein-coding genes from dozens of species, the research team reconstructed a massive evolutionary tree. In every analysis, Solarion and Meteora grouped with two other odd protist lineages to form a previously unknown supergroup called Disparia. This cluster stands as one of the major branches inside a larger section of the tree of life called Diaphoretickes.

The team ran rigorous tests to see if the clade could be an illusion caused by rapid evolution or poor data. Even after removing large numbers of fast-evolving genes, Disparia stayed intact. This kind of stability suggests the supergroup reflects a true evolutionary relationship and not a statistical artifact.

A mitochondrion that holds ancient secrets

One of the most striking discoveries hides inside Solarion’s mitochondrion. The complete mitochondrial genome spans a modest 43,872 base pairs but carries a mix of genes that rarely survive in modern eukaryotes. Several, including those for electron transport and ATP synthesis, are normally transferred to the nucleus over evolutionary time. Their presence here indicates that Solarion kept ancient features that most organisms lost long ago.

Alphafold predictions of mitochondrial SecA protein of S. arienae. (CREDIT: Nature)

The most surprising gene is SecA. In bacteria, SecA powers a major protein transport system across membranes. Mitochondria in most eukaryotes keep only faint signs of this pathway. Yet in Solarion, SecA remains encoded inside the mitochondrion itself. It even carries a membrane-anchoring segment that hints at a revived or modified version of its original function.

When the team compared SecA sequences, they found that Solarion’s version clusters with alphaproteobacteria, the bacterial group that originally gave rise to mitochondria. This strengthens the view that Sec-based transport existed in the earliest eukaryotes and was later lost across most lineages. That ancient machinery now survives only in a few deep-branching protists, with Solarion as one of the clearest examples.

Solarion also carries a nearly full set of genes tied to meiosis and syngamy. Other members of Disparia show partial sets. That pattern suggests these microbes may be capable of sexual reproduction even though scientists have never watched the process happen. Some of the genes that regulate protein stability and cell signaling in Solarion hint at a switch between its two life forms, possibly linked to a hidden sexual stage.

A Mississippi scientist at the center of the discovery

Matthew W. Brown, the Donald L. Hall Professor of Biology at Mississippi State University, served as co-corresponding author of the Nature study that announced the discovery. He said the organism “offers a rare window into early eukaryotic evolution, helping us reconstruct how the building blocks of complex life first came together.” Brown noted that the work shows how traditional cultivation can still reveal major branches of life even in an era dominated by high-throughput sequencing.

Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial SecA protein of Solarion arienae. (CREDIT: Nature)

Brown’s research career reflects a deep focus on microbial evolution. He has published more than 70 peer-reviewed studies with thousands of citations and secured nearly four million dollars in research support. His lab recently received a new grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to expand software tools used for large-scale evolutionary studies. The project, shared with Texas Tech University, will support new methods and training workshops that help scientists build stronger evolutionary datasets.

Practical Implications of the Research

The discovery of Solarion arienae expands the known tree of life and reveals a supergroup that preserves key features from the earliest complex cells. This work may help scientists refine models of how mitochondria evolved and how early eukaryotes handled protein transport and energy production.

By giving researchers a clearer view of ancient cellular machinery, the findings may guide future efforts to understand metabolic flexibility, improve evolutionary tools and interpret large environmental DNA datasets.

The work also encourages more exploration of overlooked marine habitats where other deep-branching organisms may hide.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories