I’m not an expert on Canadian housing, but my impression is that their multi-family struggles are a bit different than ours in the US. Here, there are various common legal issues that make building condos difficult, such as defect liability laws. These operate like tight underwriting in mortgage markets and strict rent controls in some urban markets that were meant to protect households, but that made the process of protection so cumbersome and costly that they just shut down the market completely, so that there are no new condos, mortgages, or apartments to offer protections on where they are binding.

In Canada, condo developers don’t have so many legal problems and they can fund their construction with deposits from the condo buyers. Apartments, on the other hand, have a more difficult time getting funding and they run into many of the same NIMBY and zoning issues that they run into in the US.

It appears that Canada has embarked on some policy reforms that are levelling the playing field, leading to more apartment construction. Figure 1 shows apartment starts now over 90,000 annually. Note, 90,000 units annually is about 2.2 units per capita x 1,000. That’s twice the annual level of apartment construction that the US has allowed for the last 40 years.

I think you can see this in Canadian construction numbers. That little bump in Figure 2 may not seem like much, but Canada and Australia are sort of like the US was in 2005. I put the US housing shortage at about 15 to 20 million units. That aggregate shortage is entirely due to the post-2007 collapse. There are several back-of-the-envelope ways to get at that 15 million number. One of them is to just count up the difference between US and Canadian construction activity since 2005 in Figure 2.

It’s weird that I’m the contrarian. This is plain evidence anyone can understand. It’s simple evidence. It’s corroborated by several other forms of simple evidence and some more sophisticated evidence.

Since it’s not conventional wisdom to take Figure 2 at face value, you can just wave your hands at it so you don’t have to explain why you’re a radical or a fanatic to the normies. So everyone does wave their hands at it. And that relieves everyone, collectively, from noting and dealing with the question, “Why did the US suddenly demand 15 million fewer units than historical trends would imply and any pre-2005 forecaster would have expected?” That’s a big number. Don’t worry. Nobody else will ask you to justify not taking note of it.

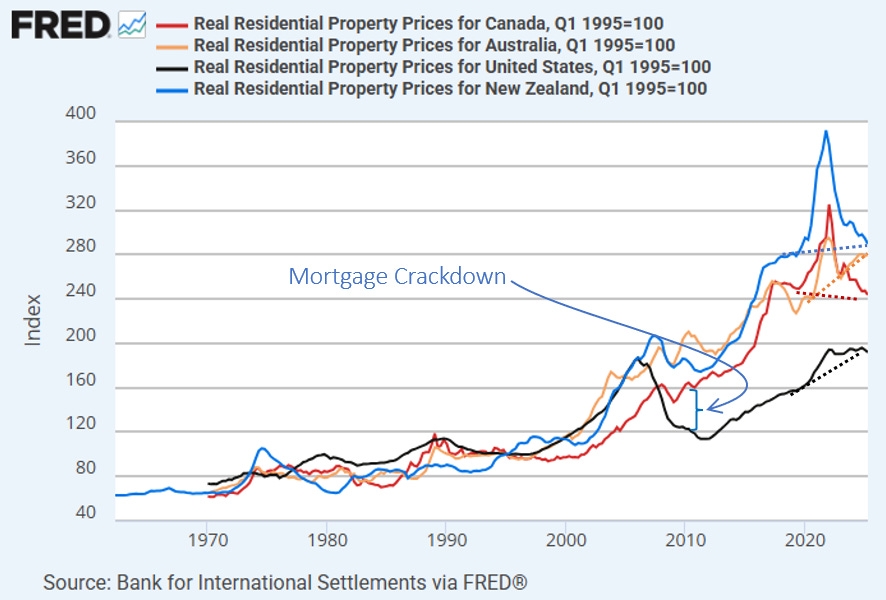

Anyway, my point is that aggregate home prices and housing expenditures were elevated in the US in 2005, but the US didn’t have a “housing shortage”. It had regional shortages, and a bit of a bubble that was caused by the mass migration of families out of those regions and into others. In Figure 3, the housing bubble in the US is responsible for that little bump up above relative prices in Australia, and the reversal of that bubble was responsible for the initial reversal back down to price trends similar to Canada.

So, what I’m saying is, solving the affordability problem in Canada and Australia won’t necessarily be associated with a huge rise in gross construction activity. It will be associated with building the right homes in the right places. That includes more building in Vancouver and Toronto, specifically, and building more apartments inside most major cities. The US has that issue, too, and some of our affordability issues would be solved in that way, without necessarily leading to more aggregate building. But, we also have the 15 million unit shortage that was created by the mortgage crackdown associated with the 25% drop in home values shown in Figure 3 and responsible for the 15 million unit shortage shown in Figure 2.

There has been a lot of short-term noise in the post-Covid economy, but if you draw a linear path from the 4th quarter of 2019 to today, real home prices in Australia and the US have continued to rise while Canada’s have flattened out.

I have also included New Zealand in Figure 3 because they have also implemented some local reforms which should change where homes are built and what types are built, similarly to Canada, and their price trends have also improved.

The increase in apartment construction in Canada appears to be related to reforms that have been developing since at least 2019, and the apartment construction numbers suggest the reforms are working.

The website listing Canada’s various initiatives is full of generally helpful programs. They seem to have collected all the reactionary hobgoblins under the heading, “Protecting Canada’s existing housing stock”. The programs include:

Prohibition on the Purchase of Residential Property by Non-Canadians

Short-Term Rental Enforcement Fund

Combatting Fraud

Confronting the Financialization of Housing

Of course, all these things exist. A lot of things exist. It’s a big world. It’s a big country. But, these issues are alike in that they are really popular and really unimportant to the problem of high housing costs. I’m heartened to suspect that the Canadian government is just throwing a rhetorical bone to the reactionaries. And, I’m heartened by not seeing any anti-immigration rhetoric there. Maybe the Canadian government is more under the control of a reasonable and competent technocracy than the US is.

I was curious what the “Financialization” point was all about. Most of the categories at the website have detailed explanations and links to more information. The “Financialization” category just says, “The Government of Canada will ensure homes are for people and not for big investment portfolios by working to restrict the purchase and acquisition of existing single family homes by very large, corporate investors.” with no links. I suspect this is very shallow chum, associated with little actual policy or enforcement activity.

This is a bit baffling, because the development of the large-scale single-family rental market in the US is entirely a result of the mortgage crackdown shown in Figure 3, which permanently reduced the price/rent ratio of homes where mortgage access had been retracted until it hit the much lower price level that would attract investor activity. How could this be something that is developing in Canada, where there wasn’t such a price collapse?

I found one really interesting post about housing in Canada. It is well-researched, and is a deep, multi-pronged construction of the wrong-headed conventional approach to the housing problem. It is so well-done, I just don’t have the bandwidth to address all the individual assumptions, causality errors, spurious correlations, and overestimations that it uses. It really is a great example of how a smart and careful observer can construct a framework for misunderstanding the housing market that would be impervious to correction.

Here’s a single, small example of the thousand cuts that would need to be addressed in the framework they develop:

Recently built housing is being especially targeted. In BC, 49 percent of all condo apartment units completed over the previous five years have been acquired by investors. In Ontario, investors have bought up by far the highest share, 57 percent, attracted by the fact that housing built after November 2018 is the only type in which tenants are not protected by rent controls.

The basic observation is undeniably true. Investors avoid housing markets with rent controls. So, where tenants are protected by rent controls, there are fewer rental units. But, the author treats investors as competition, as if an investor-owned unit means there is less housing. This is a common bias. It’s interesting to see it laid out this way. The problem, by their estimation, isn’t the lack of investment where there are rent controls. It’s the increased investment where there aren’t rent controls.

It’s a simple foundational heuristic. Investors only take homes, and do not provide them. Or, they provide them, but with extractive rents and abusive management. And, from there, really, any outcome that involves investors turns out to be bad. I could spend a month writing about all the precise ways in which that assumption leads to various unhelpful conclusions. But, it is really one simple bit of selective observation that leads to all those details. It’s similar to “immigrants took our jobs” discourse, where the observation simultaneously notes their engagement in productive activity while assuming away any fruits that we derive from that productive activity. Usually, the anti-immigrant half-truth is observed on the right and the anti-investor half-truth is observed on the left. The post excerpted above manages to mention both immigration and investors as problems. And, both left and right frequently use both these days.

Early in the post, it says, “Canada is not alone in facing these trends. Scholars focused on the political economy of housing have identified the rise of investor ownership of housing as a major driver of home price escalation and the ‘retreat of homeownership’ over the past two decades in the United States…” (and several other countries are listed). There are 3 citations for this claim about the United States. The two I could read were definitely from corners of the humanities that use this framework – capital is axiomatically bad, and the academic community’s job is to construct a language around conceptualizing its badness.

They are both engaged with placing some causal weight on new technologies as the reason for the sudden arrival of a large-scale single-family market. But, they are both clear that it had never existed before 2008, and that the proximate reason it suddenly did after 2008 was that homes were exceedingly cheap. They also both note, surprisingly, given the biases of the sources, that Blackstone, the most infamous of the corporate investors, came into the market after 2008 and had divested their positions by 2019, when real home prices in the US were still below the pre-2008 highs. The citations associate investor activity with low prices, not high prices, as far as I can tell.

(edit: If they are pushing prices higher, that confirms that they are bad. But of course, buying homes that are cheap still makes them bad because they were exploiting the foreclosure crisis to buy those cheap homes to extract profits. It would have been better for families, who aren’t axiomatically bad, to have purchased those homes. And, since the government also isn’t axiomatically bad, it surely had good reasons for preventing those families from doing that. It was protecting families from axiomatically bad lenders.)

In the US, traditionally, large investors built apartment buildings, since that is the preferable structure for managing rentals, and small scale investors tended to manage about 15% or so of the single-family stock of homes – mostly older, depreciated units. So, in the US, the division between large and small investors has been sharp, and the oddity has been the influx of some large investors into single-family homes (though the total is still a very small portion of the market).

In Canada, the response to the various regulatory obstructions on various types of housing has been for developers to build condos, in which small scale investors purchase units that they will rent out. So, multi-family buildings are more likely to have a mixture of owners and small scale landlords. In the aggregate, this has probably led to less total market share of large-scale investors in Canada relative to the US, which is probably one reason housing is expensive in Canada.

So, in Canadian discourse, the rise of large investors is within the condo and apartment market. Because of that, they don’t distinguish between single-family investors and multi-family investors, and so it was hard to get an idea of how much investor activity there has been in single-family homes in Canada.

But, first, think about what’s happening. That rise in purpose-built rental apartments is, of course, going to be dominated by large-scale investors because those are large scale projects, and there was never an economic reason to divide buildings up among many individual owners. Of course the construction of more apartments is going to mechanically lead to a rise in large-scale investors in Canada’s housing market.

So, mechanically, if Canada legalizes rental apartments, there will automatically be a populist uprising blaming large investors for whatever the perceived problems of the day are. This is a different variant of the similar issue in the US. When 10 or 15 million potential homeowners were locked out of mortgage access in 2008, two things had to happen. Prices collapsed and new home construction collapsed. And two things had to follow – more investors and rising rents. And, so there is an ocean of data just waiting for academics from the “capital is bad” fields to write papers that are supported by data that shows a strong correlation between investor activity and rising rents. And do they really need to explain the causality here? Financialization. Extraction. Market power. They know the causation axiomatically.

But, still, I am left with the question: Is there really a new market in Canada of large-scale single-family renters? That would be a blow to my claims about the US market. Well I tracked down the answer. “There are no large corporations buying existing single family houses in Canada. Simply because the math doesn’t work. This is a US phenomenon only.”

Here is a website that doesn’t seem to be biased against the idea of there being a large institutional landlord presence. Their description of the US market has some of the standard rhetoric of overstatement regarding the US market: “In the United States, corporate ownership of single-family homes is a well-documented issue. Following the 2007 housing crash, institutional investors like Blackstone and Tricon Capital began acquiring thousands of foreclosed homes, turning them into rentals. Today, such companies own significant portions of the housing market, with institutional investors accounting for one in four homes sold in the U.S.”

Their description of institutional single-family ownership in Canada: “By contrast, corporate ownership of single-family homes in Canada is far less prevalent. Analysts suggest the trend is ‘in its infancy’ here, with only one notable company—Core Development Group Ltd.—owning around 550 single-family homes in Ontario.”

So, Canada has a 5 year head start on the US. They have increased the infusion of institutional capital into housing. This naturally is bringing down costs while homeownership declines, because the obstructed form of housing was multi-family rentals, and they are now producing more of those.

I hope we can achieve that in the US. Maybe recent YIMBY wins will lead to that outcome in California. In the meantime, the influx of institutional capital in the US will be in single-family rentals. It will lead to lower costs and declining homeownership rates. And, if you were wondering what to expect, Canada is telling you that those improvements will be met with outrage for at least 5 years.

This is why we can’t have nice things.

The best we can hope for, probably, is that American governments pay lip service to those complaints without actually addressing them, which, I hope, is what Canada is doing. And, if we fail, then we will be like Canada, but without the ability for construction growth in condos or apartment buildings.

The backlash will be, unfortunately, predictable. And there may be nothing more important than defeating it.