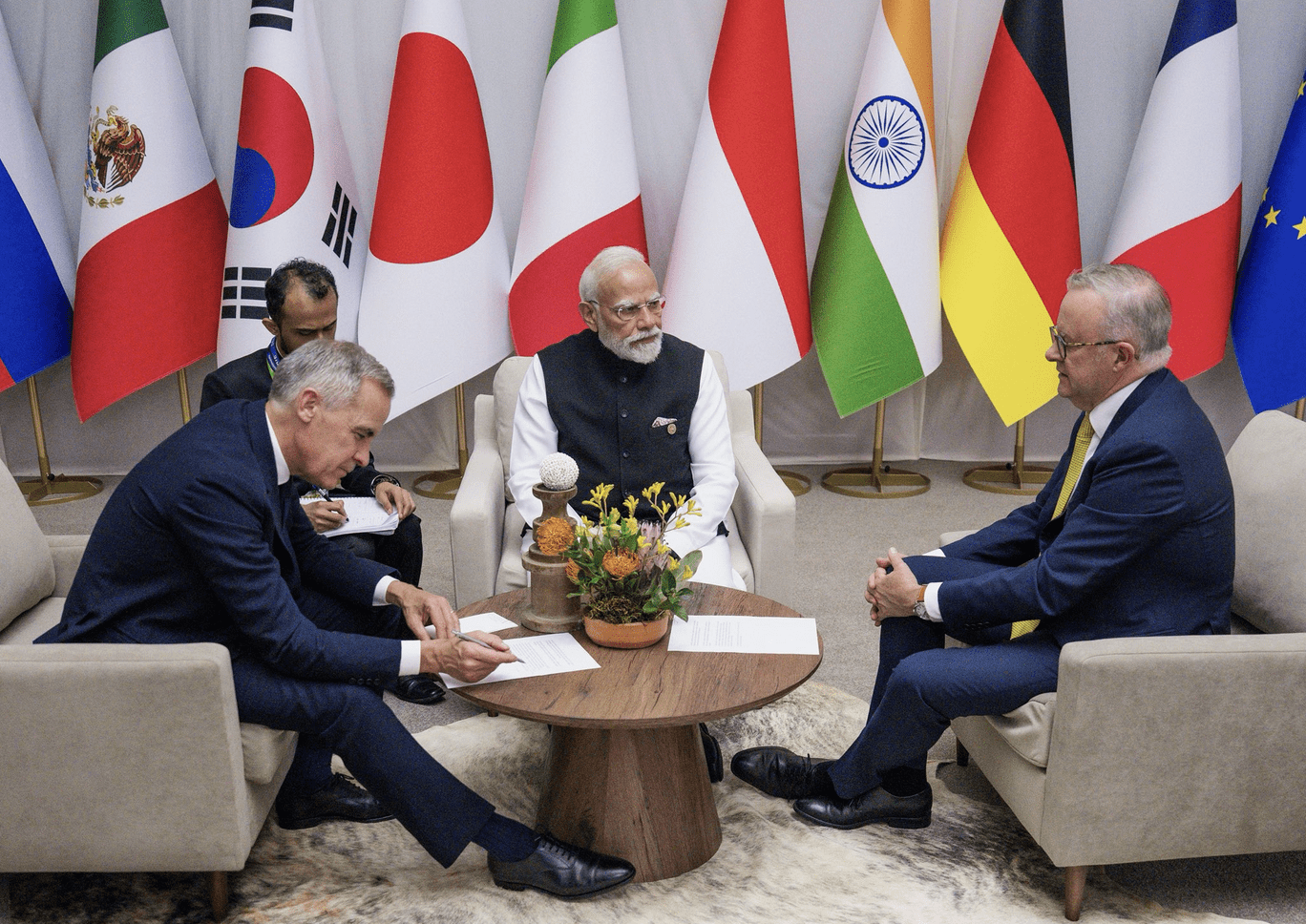

Prime Ministers Mark Carney, Narendra Modi, and Anthony Albanese in Johannesburg, November 22, 2025/Mark Carney X

Prime Ministers Mark Carney, Narendra Modi, and Anthony Albanese in Johannesburg, November 22, 2025/Mark Carney X

By David McKinnon

November 27, 2025

If the Australia-Canada-India Technology and Innovation Partnership (ACITI) announced by Anthony Albanese, Mark Carney and Narendra Modi at the G20 summit in Johannesburg works, it will be unprecedented in economic, strategic, and symbolic terms.

The initiative, which includes cooperation on AI, clean energy, and critical minerals, has significant potential to enhance Canada’s image as a reliable partner in the Indo-Pacific, assuming our commitment has staying power. Such endurance requires both persistent and consistent leadership, expertise, and bipartisan support in Ottawa, and the serious engagement of the provinces.

I say this as someone who has worked in both Canberra and Delhi and is familiar with all the relationships involved (Canada-India, Australia-Canada, Australia-India). Over the past year, I have been part of a productive track II (non-government) dialogue on the future of Canada-India relations, organized on the Canadian side by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.

Intentionally or not, many of the ideas from that dialogue have been elaborated by PM Carney and his ministers in one form or another, including on trilateral cooperation with Australia and India, notably on critical minerals.

While the ACITI as it stands is a very high-level statement of good intention, with officials committed to meet in early 2026 “to take the initiative forward”, it is a significant development between and among these three countries, including in ways that are not immediately obvious.

The fact that all three are English-speaking Commonwealth democracies is relevant, but only if we show ourselves to be reliable partners. This has not been Canada’s strong suit in the Indo-Pacific.

Shared values and familiarity are useful in driving the confidence and affinity needed for such an agreement to be productive, but too much focus on these assumed commonalities underplays the great importance of the substantial common strategic interests in this rupturing world. Shared understanding of our complementary hard strategic interests is what will drive this and other initiatives forward.

For Canada and India, the ACITI Partnership is another sign of a seriousness at the highest level to work together to ensure the security and prosperity of both countries, and to move beyond the diplomatic crisis of recent years even if each government has serious unresolved security concerns about the other.

Ottawa should welcome the willingness of Delhi and Canberra to bring Canada into this partnership, but we need to ensure we are a full and reliable part of it.

In addition to the ACITI Partnership, PMs Modi and Carney agreed to launch negotiations on a “high ambition” Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), and there have been media reports of a deal to export Canadian uranium, and expand cooperation in defence and space, among other things. Each country has too much value to the other to allow the tougher files (and domestic politics) derail the development of a serious and productive relationship.

Australia and India have developed an increasingly deep understanding and partnership since a conscious decision was made by Canberra in the 2000s to treat a democratic and increasingly prosperous India as a major partner of strategic importance to Australia’s future. That interest and commitment have been reciprocated by Delhi, especially as Australian seriousness about the relationship became a durable feature of successive Australian governments.

Casual observers may feel that the Canada-Australia relationship is almost effortless, driven by legitimately shared values and serious echoes in our respective histories, resource wealth, and governance structures. This can hide serious tensions that have arisen from different world views and approaches, driven by contrasting geography, security realities, and temperaments.

The Australian foreign and trade policy and security establishments have long been skeptical about Canada’s seriousness in the Indo Pacific. I have heard and experienced this firsthand over more than 30 years—we have been seen primarily as joiners rather than doers.

In a couple of cases, Canadian behaviour has been seen as directly impinging on Australian national interests, which they take seriously. Canberra’s willingness to come to the table trilaterally with Canada and India is a significant shift, especially given the sense in the Australian capital that Foreign Minister Penny Wong has little sentimentality for the relationship with Canada.

Ottawa should welcome the willingness of Delhi and Canberra to bring Canada into this partnership, but we need to ensure we are a full and reliable part of it. This is a long-term endeavour, not about short-term optics and narrow domestic political considerations.

Canada does seem to be approaching its international engagement with a seriousness not seen for decades, reflecting both the unmatched gravity of the moment for this country, at least since 1945, and the unprecedented pre-existing global experience of the new Prime Minister.

We need to match hard assessments of our interests at home and abroad with serious leadership to make good on those strengths.

David McKinnon is a former Canadian diplomat who was posted to Bangkok, Canberra (twice), New Delhi, and Colombo, where he served as Canada’s high commissioner to Sri Lanka and the Maldives. He is a senior fellow (non-resident) at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.