Buried nearly 1,800 miles below Earth’s surface are two vast, continent-sized structures that continue to challenge our understanding of the planet’s formation. These large low shear velocity provinces—or LLSVPs—sit just above the core, beneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean, and have mystified geologists for decades. They’re hotter, denser, and chemically different from surrounding mantle rock, yet no single theory has fully explained their origin—until now.

A new study published in Nature Geoscience proposes that these anomalies could be relics of Earth’s earliest geologic era, formed when the young planet was still enveloped in a deep magma ocean. The paper, led by Yoshinori Miyazaki at Rutgers University and Jie Deng of Princeton, offers a fresh model that links the deep mantle’s structure to chemical interactions with the core during the planet’s formative stages. The research doesn’t just fill a major gap in Earth science—it may reshape how we understand the conditions that made Earth habitable.

The new theory ties these deep-Earth giants to a planetary process involving slow leakage of core materials into the overlying magma ocean—a process that fundamentally altered the mantle’s structure and may explain both the seismic anomalies and the geochemical fingerprints detected in certain volcanic rocks.

Two Giants in the Mantle—And the Puzzle They Present

LLSVPs were first identified through seismic tomography, which uses earthquake waves to visualize the Earth’s interior. These anomalies disrupt wave patterns, slowing them dramatically compared to adjacent mantle material. The zones are thousands of kilometers wide and hundreds of kilometers high, with ragged edges and complex internal structures. Surrounding their perimeters are ultra-low velocity zones (ULVZs), thin layers where wave speeds drop by up to 90%, indicating highly unusual material properties.

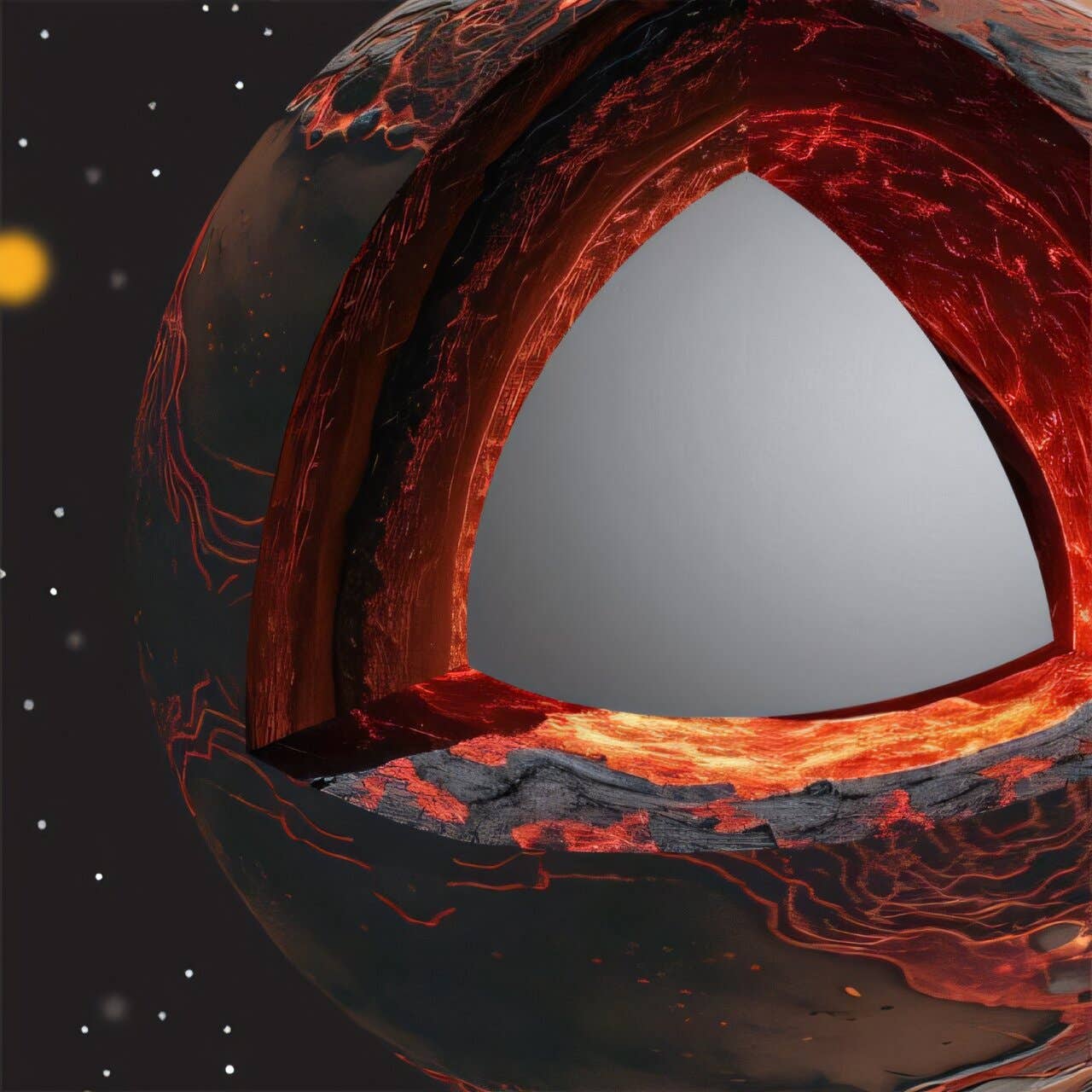

The illustration shows a cutaway of early Earth, where a hot, molten layer sits just above the core–mantle boundary. (CREDIT: Yoshinori Miyazaki)

The illustration shows a cutaway of early Earth, where a hot, molten layer sits just above the core–mantle boundary. (CREDIT: Yoshinori Miyazaki)

As detailed in The Brighter Side of News, these regions are chemically distinct and abnormally hot, but they’re not easily explained by plate tectonics or mantle convection alone. Nor do they fit models that assume a clean, layered mantle structure following planetary cooling.

Prior efforts to link LLSVPs to subducted oceanic crust or plume-related processes failed to explain their massive scale, their unique isotopic profiles, or their long-term stability. The presence of rare helium-3, tungsten, and silicon isotope anomalies in certain hotspot lavas (e.g., in Hawaii and Iceland) hinted at an ancient, undisturbed reservoir deep below—but the mechanism for preserving such a reservoir remained elusive.

A New Model: Leaking Core, Contaminated Magma Ocean

The study’s central idea revolves around a revised view of Earth’s earliest epoch, when the surface was dominated by a global magma ocean hundreds of kilometers deep. As the core began to cool, it didn’t remain chemically inert. Instead, light elements—magnesium, oxygen, and silicon—began to exsolve, or separate out, from the liquid metal and rise into the base of the magma ocean.

This steady, bottom-up chemical injection changed the composition of the magma ocean. In time, it created a basal exsolution contaminated magma ocean—abbreviated BECMO. In this model, Earth’s core acts as a slow-release source of silica and magnesium oxides, which altered how the magma ocean crystallized as it cooled.

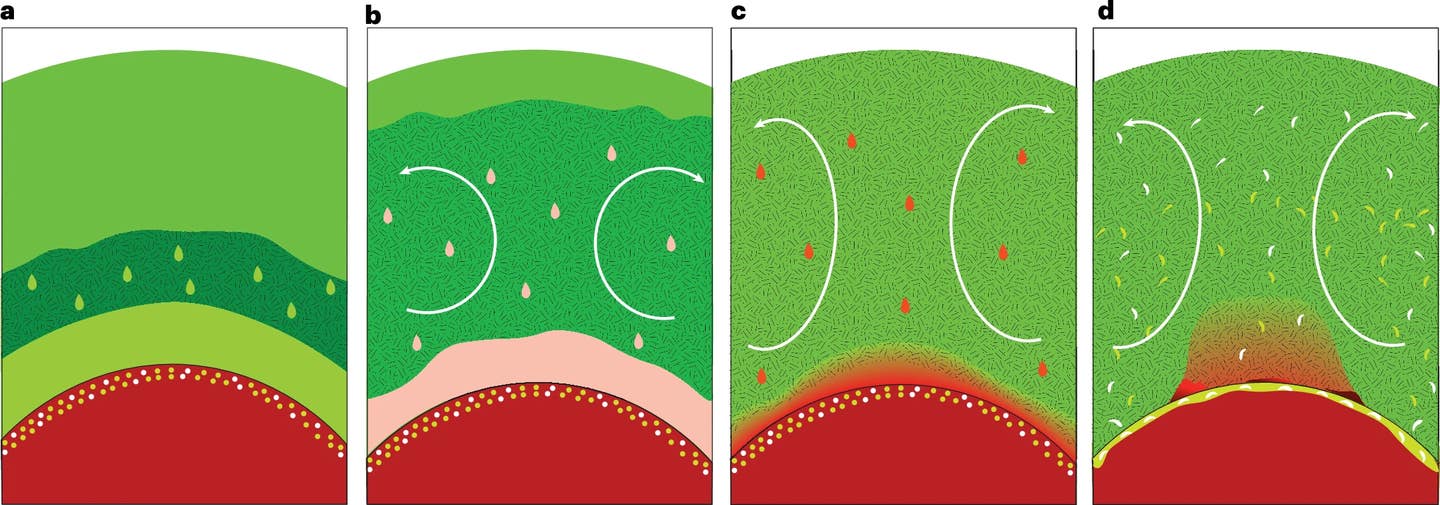

Schematic illustrating the formation and evolution of a BECMO. (CREDIT: Nature Geoscience)

Schematic illustrating the formation and evolution of a BECMO. (CREDIT: Nature Geoscience)

Without this exsolution, a simple magma ocean would leave behind a dense, iron-rich shell at the base of the mantle. But the BECMO scenario leads instead to the formation of a heterogeneous layer, rich in silicate minerals like bridgmanite, with patches of dense, stable material that eventually coalesced into the LLSVPs.

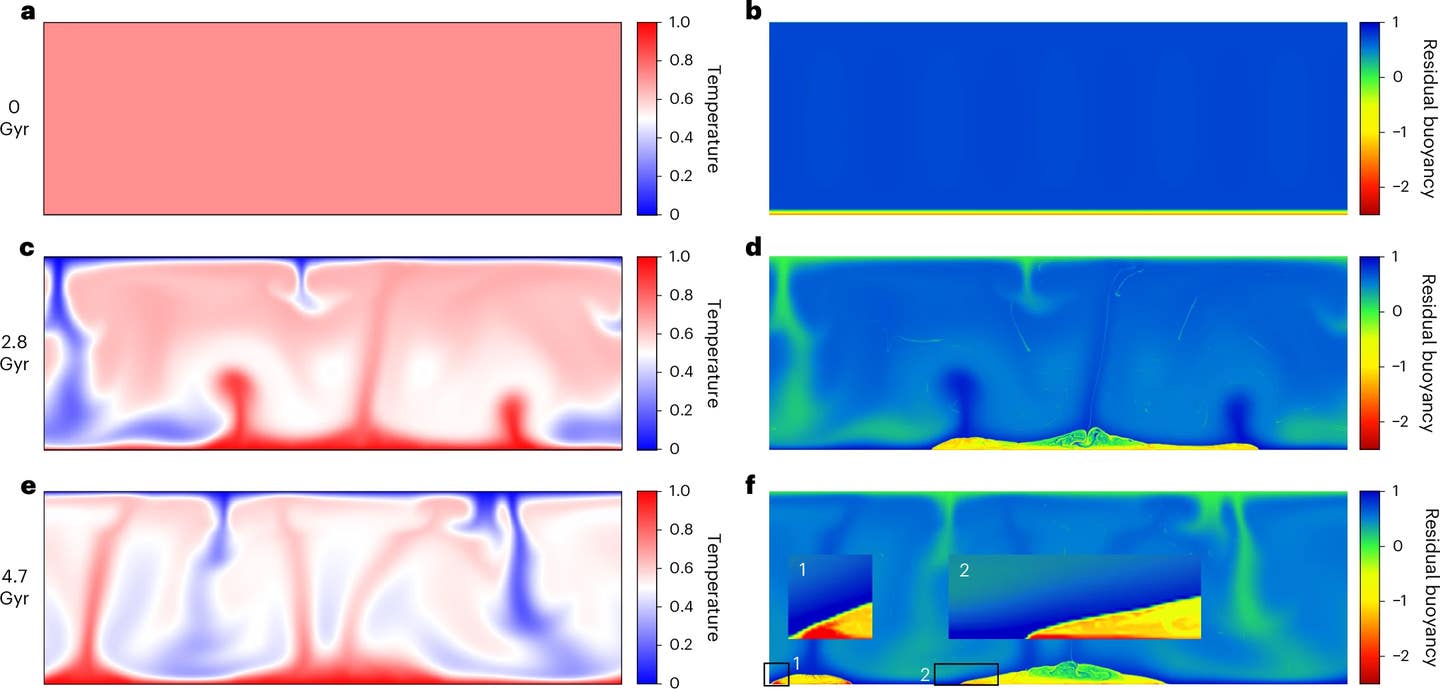

These dense piles are stable enough to persist over billions of years, yet still dynamic—shaped by mantle convection and capable of being tapped by rising mantle plumes. Simulations from the study show that this model not only reproduces the size and shape of the LLSVPs but also matches the isotopic patterns observed in volcanic rocks sourced from deep mantle regions.

A Fingerprint That Reaches the Surface

The chemical signatures carried by certain volcanic rocks have long hinted at a deep, preserved reservoir. Basalts from ocean islands sometimes exhibit high 3He/4He ratios, unusually light silicon isotopes, and rare 182W anomalies—none of which are easily explained by shallow mantle processes.

The BECMO model provides a pathway for these signals to travel from deep mantle piles to surface volcanoes. As magnesium and silicon oxides rose from the core into the magma ocean, they likely carried trace amounts of helium and tungsten, without significant iron or highly siderophile elements. These isotopic traces remained embedded in the lowermost mantle, later accessed by mantle plumes and transported to the surface.

High-resolution geodynamic modelling results of the solidified BECMO. (CREDIT: Nature Geoscience)

High-resolution geodynamic modelling results of the solidified BECMO. (CREDIT: Nature Geoscience)

While the model doesn’t account for every isotope anomaly—extreme silicon signatures may still require crustal recycling—it offers the most unified explanation yet for the coexistence of ancient and modern geochemical traits in plume-derived lavas.

Miyazaki notes in the Nature Geoscience paper that this framework links seismic structure, geodynamic simulations, and chemical data, providing a cohesive narrative for Earth’s deep interior evolution.