A new study finds that Earth’s climate flipped between chaotic and calm states during the Late Paleozoic, 360 to 250 million years ago.

During a roughly 50-million-year lull in tectonic activity, orbital rhythms steadied temperature and rainfall, and organic carbon built up in rocks that later became coal.

The work was led by Zhijun Jin, an Academician and geoscientist at Peking University. His research focuses on links between plate motions and deep time climate.

The researchers divided the interval into three phases. Two active stretches, from 360 to 330 million years ago and again from 280 to 250, surround a calmer middle period between 330 and 280.

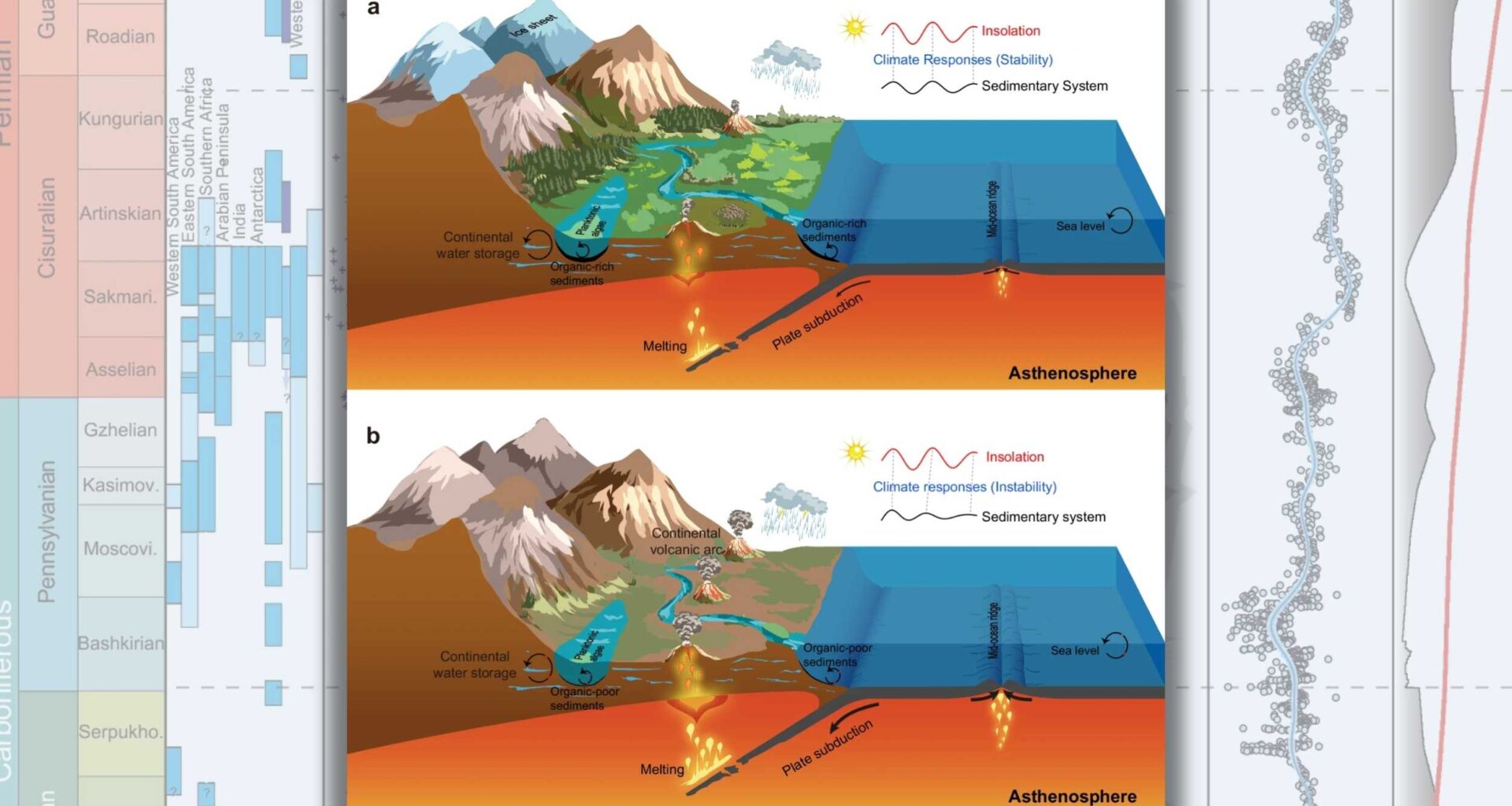

During the active pulses, volcanic carbon dioxide rose and climate variability increased. During the quiet middle slice, carbon dioxide fell, ice stabilized, and seasonal patterns lined up with orbital pacing.

“Here, we divide the late Paleozoic into three distinct tectonic phases,” wrote Jin. He noted that each phase carried its own climate signature shaped by shifts in tectonic activity and carbon dioxide.

Why the quiet phase mattered

These orbital cycles alter how sunlight is spread across latitudes. In the quiet phase, that steady push left sharp signals in sediments and sea level.

The team reports shorter and tighter sea level cycles during the lull. Active intervals stretched the beats and blurred their timing.

Evidence shows that orbital pacing can drive organic carbon burial on shorter time scales. That helps explain why calm boundary conditions turn subtle astronomical rhythm into durable rock records.

The middle phase also favored widespread forests and wetlands near the equator. Those conditions boosted organic carbon burial, long term storage of dead biomass in sediments.

Tracking signals in deep time

Late Paleozoic sea level patterns shift in response to ice growth, basin changes, and global carbon levels. Those patterns let researchers compare quiet and active tectonic intervals with a single framework.

The team focused on how tightly grouped the short cycles were during each phase. Tighter clusters signaled steady climate pacing, while broader spreads pointed to unstable conditions.

They also evaluated how well orbital pacing showed up in each interval. Clearer alignment meant that orbital rhythms had more influence when tectonic forcing was low.

Testing the tectonic climate theory

They combined plate reconstructions, geochemical markers, and paired climate and carbon models. The orbital solution they used tracks insolation over 250 million years with high precision.

A widely used Paleozoic sea level curve provided a benchmark to evaluate how short period cycles changed through time.

This long term reconstruction tracks rises and falls in global ocean levels across the era, and it anchored the timing of the peaks and troughs they counted.

They also examined subduction, where ocean crust sinks into the mantle, along with ridge length through time. Longer ridges and faster recycling point to stronger volcanic outgassing.

The model runs with 400 and 800 parts per million carbon dioxide showing a clear pattern. Higher carbon dioxide produced larger month to month swings in temperature and rainfall.

What the patterns say about carbon

The quiet middle slice produced coal and organic rich shales across many basins. Warm and humid tropics between 0 and 40 degrees latitude were prime zones for that burial.

Under calm tectonics, astronomical forcing, changes in Earth orbit and tilt, could guide ice growth and sea level with regular beats. Clear pacing helped lock carbon away in rhythm.

Active tectonics did the opposite. Frequent carbon dioxide pulses and moving shorelines disrupted habitats and muddled sedimentary signals.

The authors argue that low variability lets ecosystems keep producing and burying organic matter. High variability trims growing seasons and strips nutrients from soils and shelves.

Climate lessons from tectonics

Deep history does not set policy, but it clarifies physics. When carbon dioxide rises, the climate’s natural swings grow larger and more sensitive to external nudges.

That same sensitivity let orbital changes shake the system during tectonically active windows. In contrast, quiet interiors gave the cosmos the upper hand.

The lesson is straightforward and testable. Energy balance controls the size of natural swings, and carbon holds a major share of that balance.

Buried carbon is not gone forever either. What enters the ground in one era can reappear from volcanoes in another as plates shift.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–