In the deep waters off the coast of Indonesia, a camera quietly sank 200 meters to the ocean floor. It wasn’t part of a major research expedition or a university-backed project. The device belonged to a YouTuber.

What it captured may end up in a scientific journal.

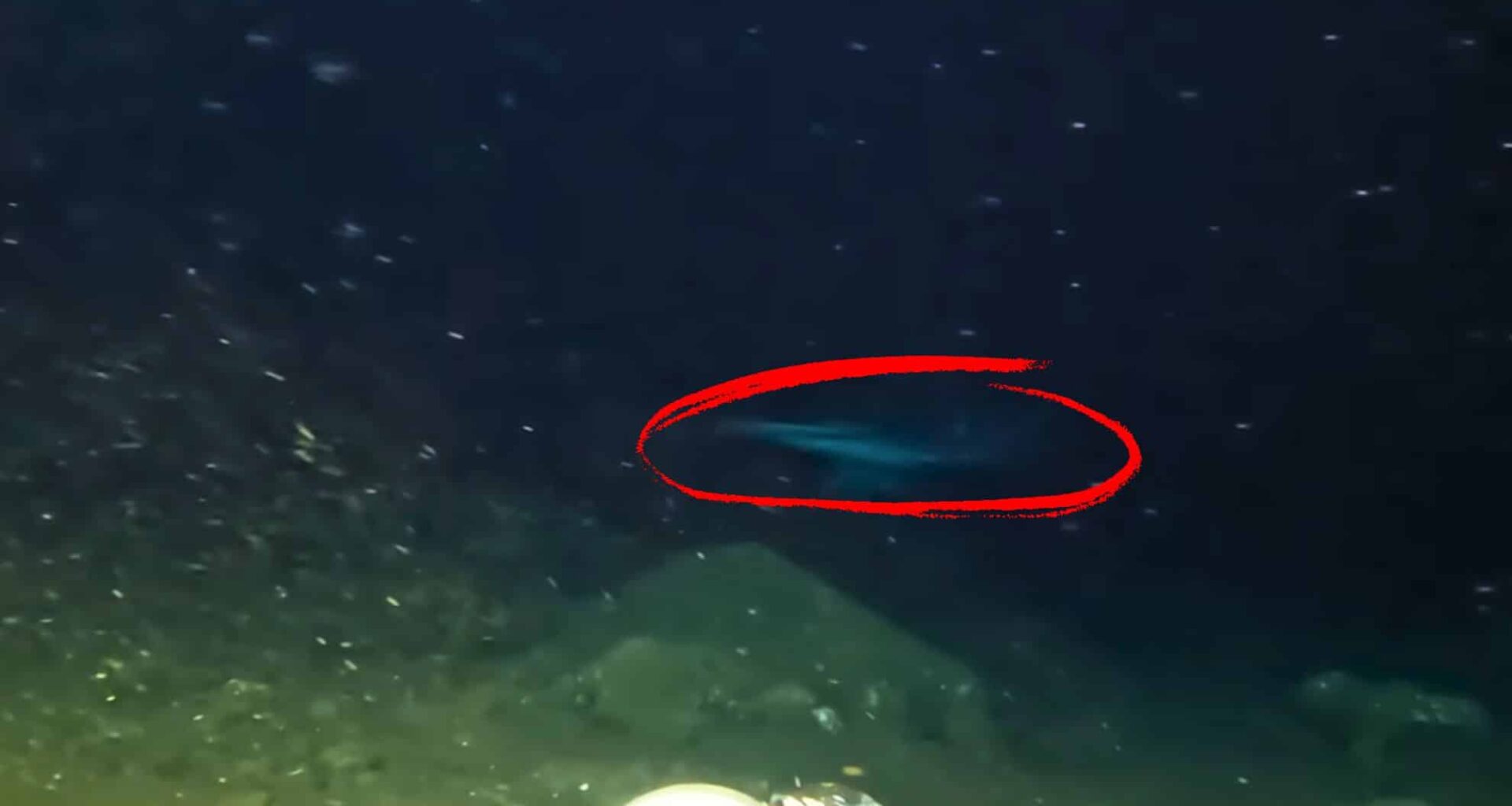

Earlier this year, British content creator Barny Dillarstone deployed his underwater rig off the coast of Bali, aiming to document rarely-seen nocturnal sea life. His video, published in July, includes footage of a ray-like creature that has left marine experts puzzled. According to Dillarstone and the scientists he later consulted, the species caught on camera doesn’t match any known animals in the region—and may not be catalogued at all.

Anomaly in the Indo-Pacific

The creature in question appears briefly in Dillarstone’s baited rig footage, gliding through the frame during the second night of his deep-sea drop in the Bali Sea. He identifies it as a stingaree, a type of small, rounded ray typically found off the eastern coast of Australia. The only two known species ever recorded near Indonesia—the Java stingaree and the Kai stingaree—are either considered extinct or have only been documented through a handful of juvenile specimens.

“It’s not supposed to be there,” Dillarstone says in his video, referring to the animal’s location. “We checked with experts. No one could say what it was with certainty.”

Barny Dillarstone captured this ‘stingaree’ (seen to the right of the bait) at the bottom of the ocean. Experts have been unable to identify the creature, and it may be new to science. Credit: YouTube/Barny Dillarstone

Barny Dillarstone captured this ‘stingaree’ (seen to the right of the bait) at the bottom of the ocean. Experts have been unable to identify the creature, and it may be new to science. Credit: YouTube/Barny Dillarstone

Marine biologists, after reviewing the footage, were unable to provide a conclusive ID. The animal’s shape, swimming pattern, and size do not align perfectly with any species currently documented in that region. “We have no idea,” Dillarstone says plainly. “Perhaps it’s new to science.”

That phrase carries weight. The World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) reports that fewer than 250,000 marine species have been officially described. But estimates of total oceanic biodiversity range as high as two million, with some studies suggesting even more remain undiscovered or unnamed. A 2023 WoRMS report emphasized the scale of this gap, highlighting how even well-studied regions of the ocean contain cryptic species complexes and undocumented fauna.

A Digital Explorer’s Accidental Find

Dillarstone, a self-funded videographer with a fast-growing YouTube channel, has been deploying custom deep-sea camera rigs across the Indo-Pacific, hoping to record new or rare creatures in their natural habitat. His goal, as stated on his channel, is to “document something the scientific community hasn’t seen before.”

In this case, he may have done just that.

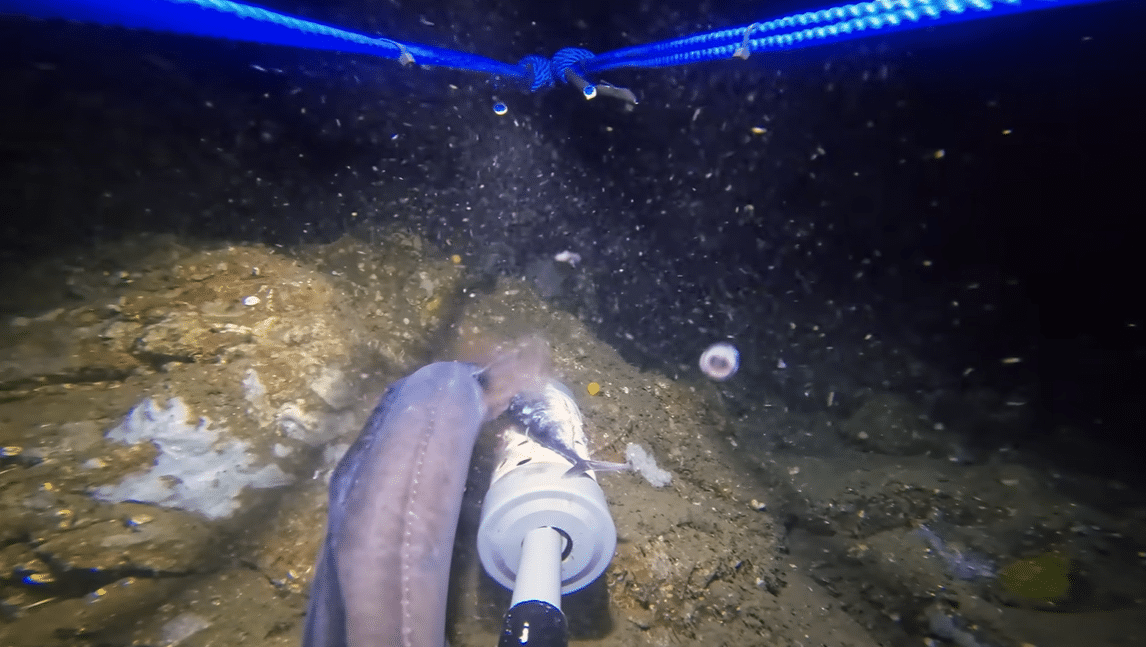

Over the two-night deployment in Indonesia, his camera recorded an impressive range of deep-sea life: conger eels, carrier crabs, nautiluses, and moray eels—many captured in motion for the first time at this depth. But the standout moment remains the unidentified ray gliding across the seabed, seemingly drawn to the bait.

“The data he’s collecting is the kind of footage we’d love to have in academic research,” said Dr. Michael Thurston, a marine biologist at SOI (Schmidt Ocean Institute), who spoke to Daily Galaxy about the video. “It’s raw, location-specific, and taken at a depth that remains under-sampled. Whether or not it’s a new species, it’s definitely a data point worth examining.”

Science Without Institutions?

Dillarstone’s work blurs the line between content creation and observational science. While the footage hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed or formally submitted to a taxonomic registry, it has attracted the attention of marine biologists tracking biodiversity patterns across Southeast Asia.

Independent observations like these aren’t unusual anymore. Platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and X have become unexpected hubs of ecological documentation, with hobbyists and creators often reaching remote environments faster than traditional institutions.

“This isn’t fringe science—it’s decentralized fieldwork,” said marine ecologist Dr. Lianne Cabral, who reviewed the footage independently. “But without tissue samples, we can’t classify it. All we have is compelling video and expert uncertainty.”

Still, she added, “this could point us toward an overlooked population or even a distinct species that survived in ecological pockets we haven’t explored.”

What the Deep Still Holds

The ocean remains the largest unknown ecosystem on Earth. More than 80% of it has never been mapped, seen, or sampled. At 200 meters deep, where sunlight barely reaches, even common species are seldom filmed in motion. Each new observation in these layers becomes a rare opportunity to expand the global marine record.

If confirmed, the stingaree-like animal spotted by Dillarstone could reshape known species distributions in the Indo-Pacific—and reopen questions around the extinction status of related rays. It might also prompt further exploration in this under-surveyed zone of the Bali Sea, where ocean currents, depth, and geography combine to create unique biological enclaves.