Canada’s current immigration approach bluntly cuts the intake of international students while simultaneously rolling out the red carpet exclusively for highly educated candidates who historically have been leaving the country in droves.

The federal government has eased barriers for immigration applications from master’s and PhD candidates, but a new report from the Institute for Canadian Citizenship (ICC) and the Conference Board of Canada found that immigrants continue to leave Canada at near-record rates.

And those who are highly educated and highly skilled are leaving at twice the rate of immigrants with less education and lower skills.

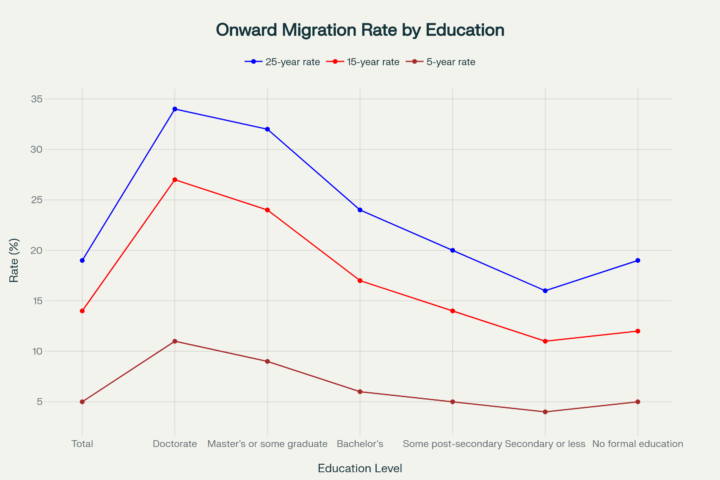

Immigrants with doctorates leave Canada at nearly three times the rate of those with only secondary education — about 11 per cent within five years and 34 per cent within 25 years. Four per cent of those with secondary education leave the country within five years, and 19 per cent leave within 25 years, according to the report.

“Reducing immigration while retention declines means we’ll just keep pouring water into the same leaky bucket,” said Daniel Bernhard, CEO of the Institute for Canadian Citizenship. “This is a story of profound self-defeat. When the most talented immigrants leave, our needs don’t leave with them.”

The statistics predict that if current onward migration rates persist, of the 380,000 immigrants arriving in 2026, 1.1 per cent (4,296) will leave after four years, 1.3 per cent (4,902) after five years, and 5.3 per cent (20,241) will have left Canada by 2031.

Immigrant Onward Migration Rates by Education Level in Canada (25, 15, 5 Year Rates) Sources: Statistics Canada; The Conference Board of Canada.

Immigrant Onward Migration Rates by Education Level in Canada (25, 15, 5 Year Rates) Sources: Statistics Canada; The Conference Board of Canada.

The report was released as Ottawa unveiled new provincial allocations for international student applications under its tightened 2026 cap.

The province of Ontario was assigned 104,780 applications, with a target of issuing 70,074 study permits — numbers that colleges say reflect a dramatic downturn. Ontario’s 24 public colleges estimate they have lost about $2.5 billion in revenue since 2023, citing a 73 per cent plunge in international enrolment following the new federal limits.

In Ontario alone, the Council of Ontario Universities predicts a staggering $1 billion financial loss during 2024-2026 due to reduced international enrolments.

Rupa Banerjee, Canada Research Chair in Economic Inclusion, Employment and Entrepreneurship, sees a significant mismatch between government messaging and reality.

“It leads me to believe that a lot of it is to manage public perception and meant to further the message that we have immigration under control and we are really only targeting the best and brightest,” Banerjee said.

Rupa Banerjee, Canada Research Chair in Economic Inclusion, Employment and Entrepreneurship. Photo: Submitted

Rupa Banerjee, Canada Research Chair in Economic Inclusion, Employment and Entrepreneurship. Photo: Submitted

“When you say you’re targeting the best and the brightest and yet you’re halving the number of international student spots, this is also inconsistent because much of the best and the brightest end up coming as international students.”

Banerjee’s research focuses on the employment integration of new immigrants. She notes that retention rates have not been strong for a long time.

“You can try to attract foreign talent all you want, but if you don’t have jobs for them, or you don’t have jobs that give them the opportunity to really thrive, then they’re not going to stay. And that’s what we’re seeing now,” she said.

“If you are underemployed and disillusioned, it’s very difficult to have a sense of belonging in Canada.”

Dr. Ghayath Janoudi’s experience is just one example of the disconnect between Canada’s immigration strategy and reality. Janoudi came to Canada in 2010 as an International Medical Graduate. He obtained equivalency, passed all of the required exams and applied for every residency match call for three years, but was unable to secure a position. He then pursued a research path, completing master’s and PhD degrees in epidemiology and AI in Ottawa.

Dr. Ghayath Janoudi, CEO of AI-biotechnology company Loonbio.Photo: Submitted

Dr. Ghayath Janoudi, CEO of AI-biotechnology company Loonbio.Photo: Submitted

Janoudi is now CEO of Loonbio, an AI-based biotechnology company that he co-founded. Janoudi notes Canada’s poor physician-per-capita ratio compared to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), making the attraction of medical professionals logical. Canada has just 2.8 physicians per 1,000 people — the OECD average is 3.7 — and only 22 per cent of international medical graduates work as doctors here despite their credentials.

“If we’re recruiting highly educated immigrants, we should ensure employers and self-regulating bodies are not allowed to discriminate based on foreign credentials or experience,” Janoudi said. “Otherwise, we’re wasting taxpayer money and attracting people under false pretenses, which does not help retain them here.”

Banerjee said across Canada highly skilled immigrants face institutional barriers. About 20 per cent of jobs are regulated, and individuals trained for these roles face significant hurdles just to become licensed, including costs, time and gaining necessary experience.

But for the remaining 80 per cent of jobs, she said employers act as gatekeepers.

“There is still insufficient engagement from employers regarding immigrant hiring, retention and inclusion,” Banerjee said. “Although a new rule will soon prohibit employers from requiring Canadian experience in job postings, this issue continues to be a major challenge.”

Even if they don’t directly ask for Canadian experience, she said there are ways this is factored into the hiring process.

Banerjee said employers have not seen immigrant integration as an important aspect, “yet they are desperate for immigrants. Specifically, they’re desperate for temporary residents.

“They lobby very, very hard for more temporary visa allocations because they do want temporary workers essentially as a source of labour. But on the other hand, when it comes to good paying, stable, secure jobs, they are very reluctant to hire immigrants. So, there’s a bit of a paradox there.”

Janoudi advocates for supporting immigrants in establishing their own businesses. “If Canada cannot stop these regulating bodies from discriminating against foreign credentialed immigrants, we should accept the fact that these highly skilled immigrants cannot become employees.

“With proper incentives placed in the immigration system, we could turn every immigrant into an entrepreneur in their field, bypassing all the barriers imposed by the workplace culture in Canada and significantly increasing the positive impact of immigrants in Canada.”

Surrey resident Gurpreet Oshan came to Canada as an international student and is now a permanent resident. She said only three of the 10 international students in her program remained in Canada; the others moved on to other countries to pursue careers.

Gurpreet Oshan. Photo: Submitted

Gurpreet Oshan. Photo: Submitted

Oshan completed an undergraduate degree at Simon Fraser University in 2008 and spent more than a decade in health care research before becoming an immigration consultant. She is currently pursuing a law degree.

She said Canada’s new immigration policy will bring the focus back to education.

“Canada is finding its academic soul again,” Oshan said. “In Canada, for a while, it has not been about education. It got lost somewhere along the way.

“Many of these universities or educational institutions have rapidly flourished or grown in two-year undergrad programs that have no career outcome for students.”

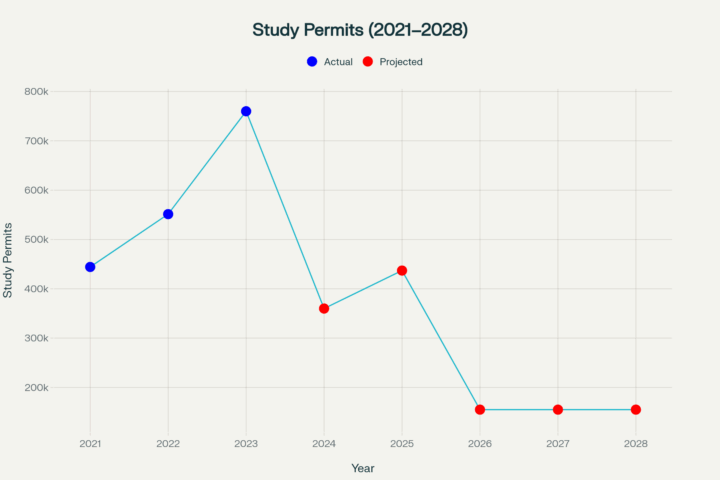

International Student Study Permit Intakes – Canada (2021–2028, Actual and Projected with Recent Policy Cuts). Graph created using IRCC data.

International Student Study Permit Intakes – Canada (2021–2028, Actual and Projected with Recent Policy Cuts). Graph created using IRCC data.

Researcher Rupa Banerjee said that international student intakes have enabled many bright, productive young people to make Canada their home.

She did an analysis last year looking at different categories of temporary residents who transitioned to permanent residents versus those who came straight from abroad. She found that postgraduate work permit holders who transition to permanent residents do very well.

“If you look at the data, the earnings of newcomers have actually gotten better,” Banerjee said. “Between 2015 to about 2020, we see this improvement. And then even after that, if you look at average numbers and permanent resident employment outcomes measured by earnings, the gap is closing.”

Please share our stories!