Retired teacher Lynn Phaneuf says he and his wife generally only use the smart TV in the living room of their Prince Albert home to watch the news.

When Phaneuf, 70, saw what purported to be an interview between CBC host Rosemary Barton and Prime Minister Mark Carney talking about cryptocurrency investment opportunities backed by the federal government, he thought he was watching a legitimate segment on a CBC streaming platform.

“With all the stuff that has been going on with Mark Carney, trying to get housing going and this and that, I thought this could be just one of those initiatives that is good for Canadians,” Phaneuf said.

The segment did not air on CBC’s platform, and it was fake — a fraudulent video made using AI to impersonate Carney, Barton and CBC branding to direct people to an investment company that was flagged by the Manitoba Securities Commission in June 2025.

Phaneuf said he had doubts throughout the weeks-long interaction with scammers that ultimately cost him $2,800. But with around $800 in profits deposited to his Canadian bank account, a legitimate cryptocurrency site tangled up in the scheme, the professional nature of the so-called financial advisers and a confusing phone call from RBC, there was always just enough reassurance to keep going, he said.

“I always use the analogy of being lost in the bush. Once you’re lost, you stop believing the things that you should believe.”

The Financial and Consumer Affairs Authority of Saskatchewan said it began tracking amounts reported lost to cryptocurrency scams in the province in 2024, and as of the beginning of November 2025, the total lost was $1.3 million.

For Canada, the reported amount lost totals more than $388 million between January 2024 and September 2025, according to the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre. Both agencies say only an estimated five to 10 per cent of victims report the fraud.

Companies ‘very well aware’ of AI-generated ads

Mathieu Lavigne, the analytic lead at the Media Ecosystem Observatory — a Canadian-based research initiative that monitors and analyzes online harms — said deepfake, AI-generated videos like the one Phaneuf encountered are a known problem for social media companies.

But the companies are taking a primarily “reactive” approach, he said.

“They’ve basically just been removing individual pages and ads when they’ve been flagged.”

Regulations for ads on social media are much looser than regulations for traditional broadcasts, he said.

Companies like Meta, which owns Facebook, rely on ad buyers to self-declare deceptive AI use and no identity verification is needed before creating a page, even pages running financial ads, Lavigne said.

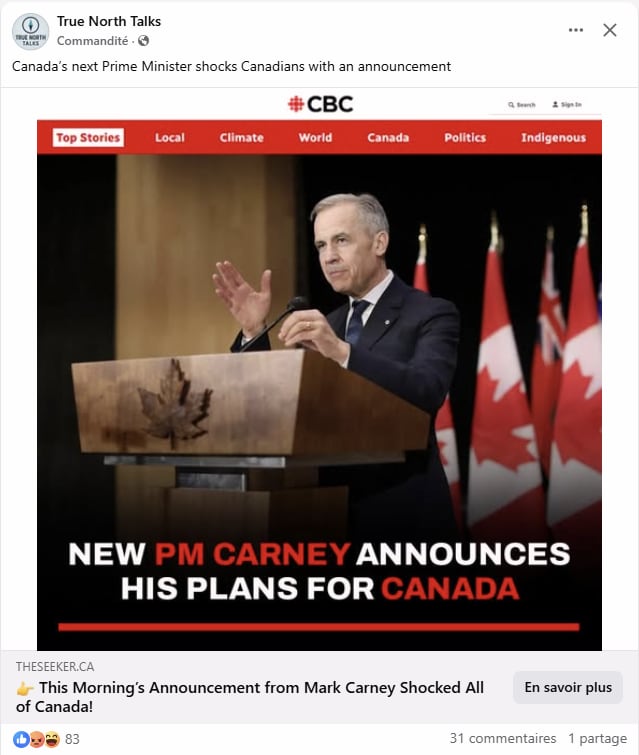

The Media Ecosystem Observatory was able to track hundreds of Facebook pages, like this one, that impersonated news organizations including CBC to direct Canadians to investment scams. (Submitted by Media Ecosystem Observatory )

The Media Ecosystem Observatory was able to track hundreds of Facebook pages, like this one, that impersonated news organizations including CBC to direct Canadians to investment scams. (Submitted by Media Ecosystem Observatory )

“Right now it is possible for any individual around the world to create a page and start buying ads right away that try to defraud Canadians.”

The problem is extensive, he said. His team identified over 200 pages on Meta platforms running ads like the one Phaneuf encountered. One video had been seen by more than 100,000 Canadians.

He said information from Meta’s ad library shows that more vulnerable Canadians like the elderly are often targeted.

The scam

The fake segment directed Phaneuf to a website called TW Pro, which he said later suddenly became PlusTW. The site displayed stock and trading information for recognizable companies like Apple and cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Dash. Phaneuf said he was able to verify that information against the stock exchange in real time.

With time on his hands during retirement, and an apparent endorsement from the prime minister, he thought investing might be interesting and fun.

“I was not trying to make big money out of it. I didn’t need the big money out of it. I just thought, ‘Oh, this is something to try,’” he said.

After he created an account, a series of self-described financial advisers began calling him from Canadian numbers. One gave the name of a real financial adviser based in Toronto, he said.

His first investment was $365, paid by credit card. After 10 minutes on the phone with someone, he’d earned a profit.

“The earnings were not great, but it was an earning every time,” he said.

Once he ensured he could withdraw his money, he decided to invest $3,000, an amount he could afford to lose. That was the limit he gave himself for the investment project.

Unclear call from RBC

The site asked him to send the money through crypto.com — a Singapore-based company registered to operate in Canada through the Canadian Securities Administrators — using an e-transfer. The move concerned his bank.

“RBC phoned me and said, ‘Are you sure you want to do this?’” Phaneuf said.

They told him cryptocurrencies often involve scams, but when he asked if RBC had problems with the specific company, crypto.com, the representative said no, Phaneuf said.

“He couldn’t give me an answer: is this OK or is this not OK?”

The call lasted five minutes.

In a statement to CBC, RBC said it would not comment specifically on Phaneuf’s case due to client privacy, but that the company was in contact with him directly about the situation.

“We recognize that we have an important role to play in helping to protect our clients from fraudsters and educating Canadians about staying vigilant in an ever-evolving threat landscape,” the statement said.

A spokesperson for crypto.com told CBC the company “is not affiliated” with either PlusTW or Pro TW “in any way.”

Pressure to invest

Phaneuf said the pressure to invest increased. When he resisted, the financial advisers became harder to get on the phone. He said he tried to withdraw money and “the phone went dead.” Requests to close his account were similarly ignored.

Normally, he’s able to spot scams and can avoid things like fake emails or phishing scams, he said.

“I was mad because I fell for this one hook, line and sinker.”

Phaneuf said he reported the loss to Prince Albert city police but got a call informing him that they would not pursue it, despite classifying it as theft. He was told there was no need to submit his witness statement, he said.

After CBC contacted Prince Albert police for comment, a spokesperson said they had determined Phaneuf’s case “requires additional attention” and reopened the file.

“After reviewing the file, we recognize that the initial assessment did not meet our expected standard of service,” Chief Patrick Nogier said.

“We need to be upfront,” Nogier said when asked about the police service’s ability to handle cybercrime.

“We do not have the capabilities and the expertise.”

Nogier said cases involving cybercrime are often beyond the capacity of mid-sized police forces like Prince Albert’s.

Prince Albert Police Chief, Patrick Nogier (Aishah Ashraf/CBC)

Prince Albert Police Chief, Patrick Nogier (Aishah Ashraf/CBC)

He called the initial assessment of Phaneuf’s case “concerning” given how often cybercrime goes unreported.

Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre outreach officer Jeff Horncastle said victims of fraud should file reports with both their local police and the anti-fraud centre, as it is a separate reporting process.

He said fraud is “very underreported” for multiple reasons, including victims being confused about where to go and having challenges reporting to police.

Learning about the scam

Phaneuf’s wife asked him to take a cybersecurity course at the University of Saskatchewan through its continued learning program in the fall.

While attending the virtual course, he heard a very familiar tale of fraudsters earning trust through phone calls over time, returning some money to victims in order to get them to invest more, and then disappearing with their money, he said.

“They could have just been pointing at me.”

While Phaneuf didn’t tell his teacher, Canada Research Chair in Security and Privacy Natalia Stakhanova, about his experience, Stakhanova said other seniors in her class have mentioned brushes with AI-powered scams.

University of Saskatchewan computer science professor Natalia Stakhanova teaches a cybersecurity course for seniors. (Katie Swyers/CBC)

University of Saskatchewan computer science professor Natalia Stakhanova teaches a cybersecurity course for seniors. (Katie Swyers/CBC)

“A lot of people don’t realize the extent of the AI these days and the capabilities are growing daily,” Stakhanova said.

“Criminals are getting, becoming more and more creative.”

Scams are now more sophisticated and more believable than “we are accustomed to seeing,” she said.

Experts say education is key to fighting new forms of fraud.

All individuals and companies dealing with financial securities are required to be registered with the Canadian Securities Administrators and can be looked up there.

Phaneuf’s advice is to keep your bank account information away from anyone asking for money on the internet.

“Don’t let any money out because there’s a good chance you’ll never see it again.”