Sample preparation

The magnetic chiral tubes were fabricated by combining TPL and ALD. We applied the additive manufacturing methodology described in ref. 31 to 3D polymer wires that contained helical reliefs. These were prepared by TPL using a Photonic Professional GT+ system (Nanoscribe) in three steps. First, negative photoresist IP-Dip was dropped onto a fused-silica substrate (25 × 25 mm2, 0.7 mm thick). Second, an infrared femtosecond laser (wavelength, 780 nm; power, 20 mW) was focused inside the resist exploiting the dip-in laser lithography configuration for the exposure. Third, the whole substrate was immersed in propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate for 20 min and isopropyl alcohol for another 5 min. After the polymer had been dried in ambient conditions, the sample was put into a hot-wall Beneq TFS200 ALD system. We conformally coated the polymer with a 30-nm-thick nickel shell after depositing 5-nm-thick Al2O3 using the plasma-enhanced ALD process presented in ref. 28. The detailed preparation process is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

BLS

The spin dynamics were investigated by µBLS at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2). The samples were mounted on a piezo stage, which allowed movement in steps of 50 nm underneath the laser focus. Positive and negative external magnetic fields were applied by permanent magnets mounted in different orientations along the x axis, with the ACMs positioned parallel to the x axis. A green laser (wavelength, 532 nm) with a power of 3 mW was focused on the surface of the helical magnet using a 100× objective lens with a numerical aperture of 0.75. The full-width at half-maximum of the focused laser spot was experimentally determined to have an upper bound of 436 nm (Supplementary Fig. 15). The s-polarized component of the scattered light was passed through a Glan–Taylor polarizer and directed to a six-pass tandem Fabry–Perot interferometer. In the µBLS set-up, the focused laser light produced a cone of incidence angles around the optical axis of the lens. The backscattered light contained photons that interacted with magnons having different in-plane wavevectors +k and –k, with k magnitudes ranging from 0 to ∼17.7 rad µm−1.

XMCD images

Magnetic chiral tubes of right-handedness (Extended Data Fig. 1a) and left-handedness (Extended Data Fig. 1d) were fabricated on a silicon nitride window membrane. This scaffold supports the ACMs, suspending them over empty space by their ends. These structures were imaged using scanning transmission X-ray microscopy at the UE46_MAXYMUS endstation42 of the BESSY II electron storage ring operated by the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin für Materialien und Energie. We performed measurements in multibunch hybrid operating mode, where the sample is illuminated by X-rays stroboscopically at a repetition frequency of 500 MHz. We acquired static transmission images using circular polarized monochromatic X-rays with left- and right-handed circularities at the nickel L3 absorption edge (854.5 eV). This energy, slightly offset from the absorption maximum, was chosen to optimize the XMCD signal while minimizing signal loss caused by the thickness of the structures. To remove artificial intensity offsets caused by occasional noise artefacts inherent in the measurement technique (such as the detection of zeroth-order diffracted light, electronic noise from the circuits or thermal fluctuations in the electronics), we applied a dark-field correction to all the transmission images as follows:

$${I}_{\mathrm{corrected}}=\frac{{I}_{\mathrm{sample}}-D}{{I}_{\mathrm{vacuum}}-D}$$

where D represents the dark-field factor, which can have values between 0 and 1. For our transmission images, a dark-field factor between 0.9 and 0.92 was applied43.

We transformed the transmission images into a dimensionless logarithm scale of normalized intensity, ln(Inorm), using the equation:

$$\mathrm{ln}\left({I}_{\mathrm{norm}}\right)=\mathrm{ln}\left(\frac{{I}_{\mathrm{measured}}}{{I}_{0}}\right)=-\mu t$$

where Imeasured is the intensity of the transmission images measured, I0 is the reference intensity in the empty space, µ is the absorption coefficient (which depends on the circularity of the light) and t is the material thickness. To qualitatively determine the relative direction of the magnetization with respect to the X-ray wavevector k, we calculated the XMCD factor in each point of the measured transmission images:

$$\mathrm{XMCD}\,\mathrm{factor}\propto {\mu }^{-}-{\mu }^{+}.$$

The resulting XMCD images were processed with a Gaussian filter, using σ = 0.5 pixels. This approach gives us estimates of the azimuthal magnetic orientation.

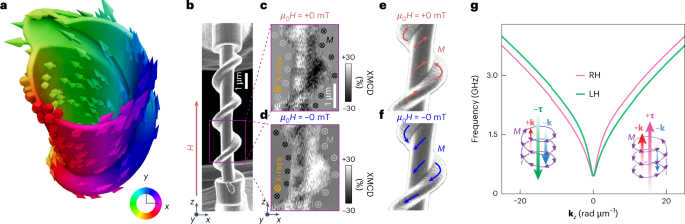

We imaged both RH and LH ACMs using a measurement configuration where the X-rays are incident normally on the structure’s main axis along the \(\hat{z}\) direction. This measuring set-up provided sensitivity to the out-of-plane component of the magnetic configuration. The results for the RH ACM (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b), discussed in the main text, reveal that the remanent azimuthal magnetic orientation is determined by the gyration direction of the helix (Extended Data Fig. 1c). A similar behaviour is observed for the LH ACM: the transmission image corresponds to the red-highlighted region in Extended Data Fig. 1d, showing both tubular and helical regions of the ACM (Extended Data Fig. 1e).

XMCD images of the remanent state, measured at µ0H = ±0 mT, show an azimuthally oriented out-of-plane component. As with the RH ACM, this results in a contrast reversal with the direction of the saturating field, confirming that the azimuthal orientation is determined by the helix gyration direction (Extended Data Fig. 1f). When we compare XMCD results for the RH and LH ACMs, we observe that both exhibit similar magnetic patterns but with opposite contrast, indicating that the gyration is reversed between RH and LH ACMs. This implies that the handedness of the magnetic texture is intrinsically determined by the structural chirality of the ACM.

To further understand how the helix direction imprints the gyration direction of the magnetic texture, we present schematics illustrating the X-ray detector view and the projection of the magnetization along the X-ray wavevector view (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the RH ACM, the helix gyration produces a counterclockwise texture for µ0H = +0 mT (Supplementary Fig. 3a) and a clockwise texture for µ0H = −0 mT (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The opposite occurs in the LH ACM, where a clockwise texture is generated with µ0H = +0 mT (Supplementary Fig. 3c) and a counterclockwise texture with µ0H = −0 mT (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Thus, the contrast observed in the XMCD images in Extended Fig. 1 can be explained by the relative projection of the magnetization along the X-ray wavevector, where white contrast appears when the projection is parallel to k, and black contrast appears when it is antiparallel.

Simulation

Micromagnetic simulations were conducted using MuMax3 software44, which solves the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation on a finite difference grid. We considered a nickel ACM consisting of a tube with inner radius of 220 nm and a thickness of 30 nm which intersects a hollow helix of ellipsoidal cross-section. The helix had a pitch of 2,000 nm, a diameter of 740 nm, cross-sectional inner major and minor radii of 120 nm and 70 nm, respectively, and a thickness of 30 nm. The helix and tubular segment are directly connected to each other (Supplementary Fig. 5b), and are coupled via both exchange and magnetostatic interactions. The saturation magnetization was set to Ms = 490 kA m−1 and the exchange stiffness to Aexc = 8 pJ m−1 (ref. 45). The system was discretized into 160 × 160 × 384 cells of dimension 5 × 5 × 5.2 nm3. Six repetitions of periodic boundary conditions along the z direction were used.

Hysteresis diagrams of the structures were computed by sweeping an applied field parallel to the tube axis with a 2° misalignment between +1 T and −1 T and back to +1 T. Additionally, a constant background field of 0.7 mT along the x,y diagonal was applied. The magnetic ground state was computed in between specified field increments by first using the steepest conjugate gradient method46 to minimize the energy and then solving the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation without a precessional term. The resulting ground states provided the initial state for the computation of the toroidal moment and the dynamic behaviour.

The toroidal moment for a given magnetization distribution \({{m}}_{0}({\mathbf{r}})\) was computed per layer according to:

$${\mathbf{\uptau }}\left({{m}}_{0}\right)\mathop{=}\limits^{\text{def}}\frac{1}{A}{\iint }_{A}{\rm{d}}x{\rm{d}}y{\mathbf{r}}\times {{m}}_{0}({\mathbf{r}})$$

with r the position vector using the tube axis as the origin and A is the area.

The dynamic simulations were conducted as follows. A dynamic field \(h={h}_{0}{\mathrm{sinc}}\left(2{{\uppi}}{f}_{{\rm{c}}}\left(t-{t}_{\mathrm{delay}}\right)\right)\) was confined to a strip of width 20 nm along the longitudinal axis of the tube in the centre of the ACM. Here, we used the amplitude h0 = 3 mT, the cut-off frequency fc = 15 GHz and the time offset tdelay = 26.7 ns. The strip covered only half the cross-sectional area of the ACM to excite both odd- and even-numbered m modes. The dynamic field was applied perpendicular to the tube axis. The simulations were run for a total time of 53.3 ns and the magnetization was sampled on the surface of the tube along the tube axis every 33.3 ps. The damping was set to α = 10−3 and increased quadratically to 1 near the ends of the structure. The dispersion shown in Fig. 4b,d was obtained by performing a 2D fast Fourier transform over the dynamic magnetization sampled on the tube along the z axis.

Analytical dispersion

The simulated dispersion in Fig. 4c,d is plotted together with data obtained from the analytical model proposed by Salazar-Cardona et al.28 for nanotubes with helical equilibrium magnetization. The analytical dispersion is given by

$${\omega }_{m}({\mathbf{k}})={\omega }_{M}\left[{{\mathscr{A}}}_{m}({\mathbf{k}})+\sqrt{{{\mathscr{B}}}_{m}(k){C}_{m}({\mathbf{k}})}\right]$$

with \({\omega }_{M}=\gamma {\mu }_{0}{M}_{{\rm{s}}}\), γ is the gyromagnetic ratio and k the wavevector. The index m denotes the azimuthal mode. \({{\mathscr{A}}}_{m}({\mathbf{k}}),{{\mathscr{B}}}_{m}({\mathbf{k}}),{C}_{m}({\mathbf{k}})\) are the dynamic stiffness fields. The frequency non-reciprocity is determined by the magnetochiral stiffness field \({{\mathscr{A}}}_{m}({\mathbf{k}})=\)\(-\chi {\mathscr{K}}(m,{\mathbf{k}})\sin \left(\theta \right)+p(N(m,{\mathbf{k}})-\frac{2m{\lambda }_{\mathrm{exc}}^{2}}{{b}^{2}})\cos \left(\theta \right)\). Here, θ is the angle of the magnetization with respect to the tube axis, b is the geometrical factor depending on the radius, λexc is the exchange length, p = ±1 is the polarity of the magnetization and χ = ±1 is the helicity (Supplementary Text). The functions \({\mathscr{K}}(m,{\mathbf{k}}),{\mathscr{N}}\left(m,{\mathbf{k}}_{z}\right)\) are demagnetizing factors and depend only on the geometry. The analytical data shown in Fig. 4c,d are obtained from equation (18) (Supplementary Text) in the thin-shell approximation where t ≈ λexc, with t the thickness λexc. The frequency non-reciprocity sweeps shown in Fig. 4e–g were computed based on equation (18) (Supplementary Text) in the ultrathin-shell approximation where \(t\approx {\lambda }_{\mathrm{exc}}\ll r\) and r is the mean radius of the tube. In all other cases, the dispersion was computed in the thin-shell limit. For the tube sizes under consideration, the two approximations were in good agreement for small values (≲10 rad μm−1) of kz. Complete expressions for the dispersion in both approximations are given in Supplementary Text.

The magnetic parameters used for the analytical calculations on nickel are identical to those of the simulations. The thickness of the tube was set to 30 nm. A good quantitative agreement between the analytical theory and the simulations was achieved using an effective mean radius of r = 300 nm and a magnetization angle of θ = 20° (Supplementary Fig. 8) in the analytical model. Note that this effective radius is larger than the mean radius of the simulated tubular region (235 nm). However, the corresponding mean diameter used for the analytical calculations (600 nm) is almost identical to the cross-sectional mean major-diameter of the ACM (590 nm), that is, the maximum distance between opposing sides along a cross-section of the ACM (Supplementary Fig. 5b). For the computations on permalloy in Fig. 4f,g, we used magnetic parameters Ms = 800 kA m−1 and Aexc = 13 pJ m−1.