Stars form in massive clouds of gas called molecular clouds. As they form, they accrete gas from these clouds, and as the stars rotate, gas and dust accumulates in a rotating disk around the star called a protoplanetary disk. As the name makes clear, this is where planets form by accreting material from the disk.

That’s a simple explanation of an extremely complex process that’s an ongoing subject of research in astronomy. Decades of research have reinforced the basic premise that stars gradually accrete material from these disks, while some is “blown” away by the star’s radiation, and some forms planets. Over time, the protoplanetary disk dissipates, the star ceases accreting and reaches its final mass, and planets cease formation.

However, it’s difficult to see into these environments to ascertain what’s going on. The entire process is shrouded by thick gas and dust, and much of what’s known is partly based on observations and partly based on theory. So this explanation doesn’t fit all stars. It works for stars about the same size as the Sun, but doesn’t work for intermediate mass stars. When astronomers observe intermediate mass stars with between 1.5 and 4 solar masses, they find that they accrete mass more rapidly than expected.

New research shows that rather than their accretion declining with age, intermediate mass stars experience rapid growth spurts later in their formation. Counter-intuitively, this doesn’t inhibit planet formation, it actually allows for the growth of gas giants like Jupiter.

The research is titled “Evolution of the Accretion Rate of Young Intermediate-mass Stars: Implications for Disk Evolution and Planet Formation.” It’s published in The Astronomical Journal, and the lead author is Sean Brittain. Brittain is a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Clemson University in South Carolina.

“Like people, stars appear to go through an adolescent phase where they eat voraciously,” Brittain said in a press release. “They grow faster later in life than we expected.”

The research is focused on two types of stars: intermediate mass T-Tauri stars, and Herbig stars. T-Tauri stars are young, pre-main sequence stars, and Herbig stars are what T-Tauri stars evolve into. Herbig stars are closer to being on the main sequence, but are still forming and are still embedded in their disks. They’re more massive and hotter than the Sun.

“This work presents a study of the evolution of the stellar accretion rates of pre-main-sequence intermediate-mass stars,” the authors write in their research article. “We compare the accretion rate of the younger intermediate-mass T Tauri stars (IMTTSs) with the older Herbig stars into which they evolve.”

As stars accrete material, they also radiate energy, and that’s at the heart of the new research. Measuring the radiated energy let’s astrophysicists measure a star’s growth rate.

“When material falls onto a star, a lot of energy is released. Just like when you drop a chair, it will make a noise or even break. In the case of material being accreted, the energy released is much greater. We can see this as extra radiation coming from the system, and this allows us to determine the rate at which the stars grow in mass,” Brittain said.

When observing Herbig stars, the researchers saw their accretion rate grew with age as the star’s approached maturity.

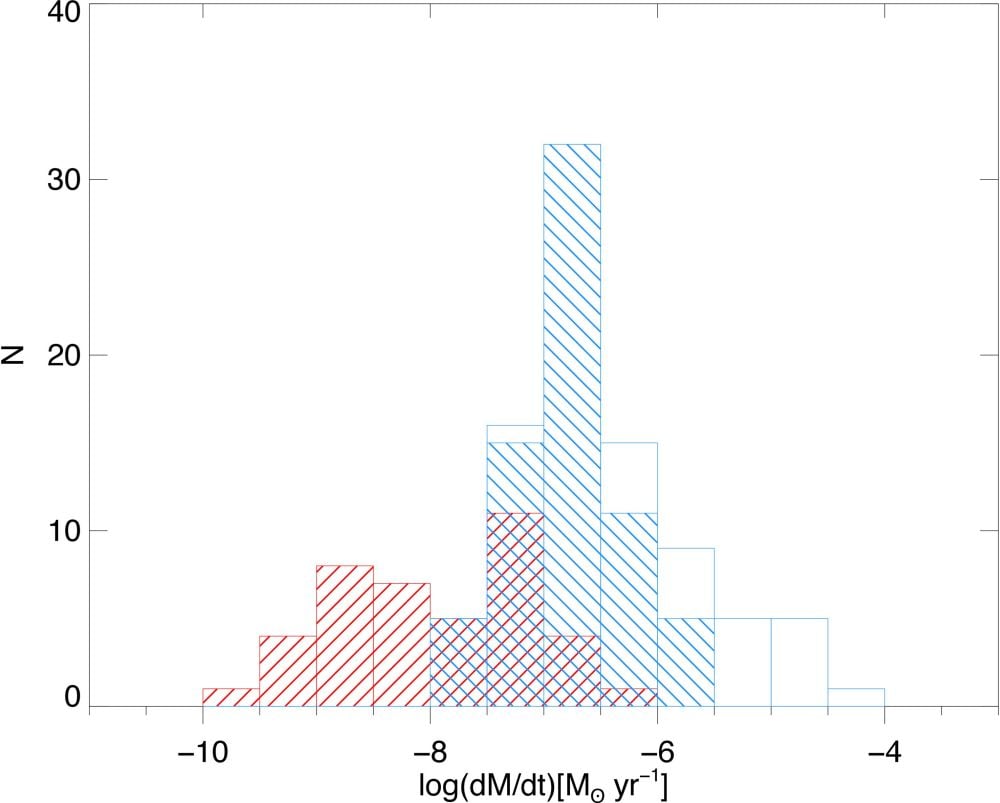

*This figure from the research shows the accretion rates for Intermediate Mass T-Tauri Stars in red, and Herbig stars in blue. “The median stellar accretion rate of Herbig stars is 1 order of magnitude higher than the median stellar accretion rate of IMTTSs,” the authors write. Image Credit: Brittain et al. 2025. AnJ*

*This figure from the research shows the accretion rates for Intermediate Mass T-Tauri Stars in red, and Herbig stars in blue. “The median stellar accretion rate of Herbig stars is 1 order of magnitude higher than the median stellar accretion rate of IMTTSs,” the authors write. Image Credit: Brittain et al. 2025. AnJ*

“This implied that the disks surrounding these stars must start out to be very massive indeed. This would pose a problem because such massive disks would be unstable and break up before planets even have the chance to be formed,” said Rene’ Oudmaijer, a member of the team from the Royal Observatory of Belgium.

It might seem like massive disks would encourage planet formation, but the opposite is true. When a disk is about 10% as massive as its star, or greater, they become unstable. They can rapidly fragment into clumps, inhibiting the gradual formation of planets via collisions and accretion.

When the researchers observed the IMTTSs, they found that their accretion rate was more than 10 times lower than their more evolved counterparts, the Herbig stars. “Instead of higher accretion rates, we found values that were up to 30 times lower than those of the Herbig stars. In a way, this would solve the mass problem, as the disk does not need to be so massive to begin with,” said Gwendolyn Meeus of the Universidad Autonoma de Madrid in Spain.

So, declining accretion rates for aging Herbig stars imply massive disks that are unstable, and the instability inhibits planet formation. Even lower accretion rates for the IMTTSs seems to solve the mass problem because the disk can initially be smaller and still allow for the formation of gas giants.

But this presents another problem: the older stars are accreting mass much more rapidly than their younger counterparts. Theory predicts that this can’t be true; basically, it doesn’t make sense. Why would a star accrete less mass when there’s more available, and more mass when there’s less available?

“Theory would predict that the stars accrete less material over time, not more. This new finding needs an explanation based on well-grounded physics if we are to change our current thinking,” Brittain said.

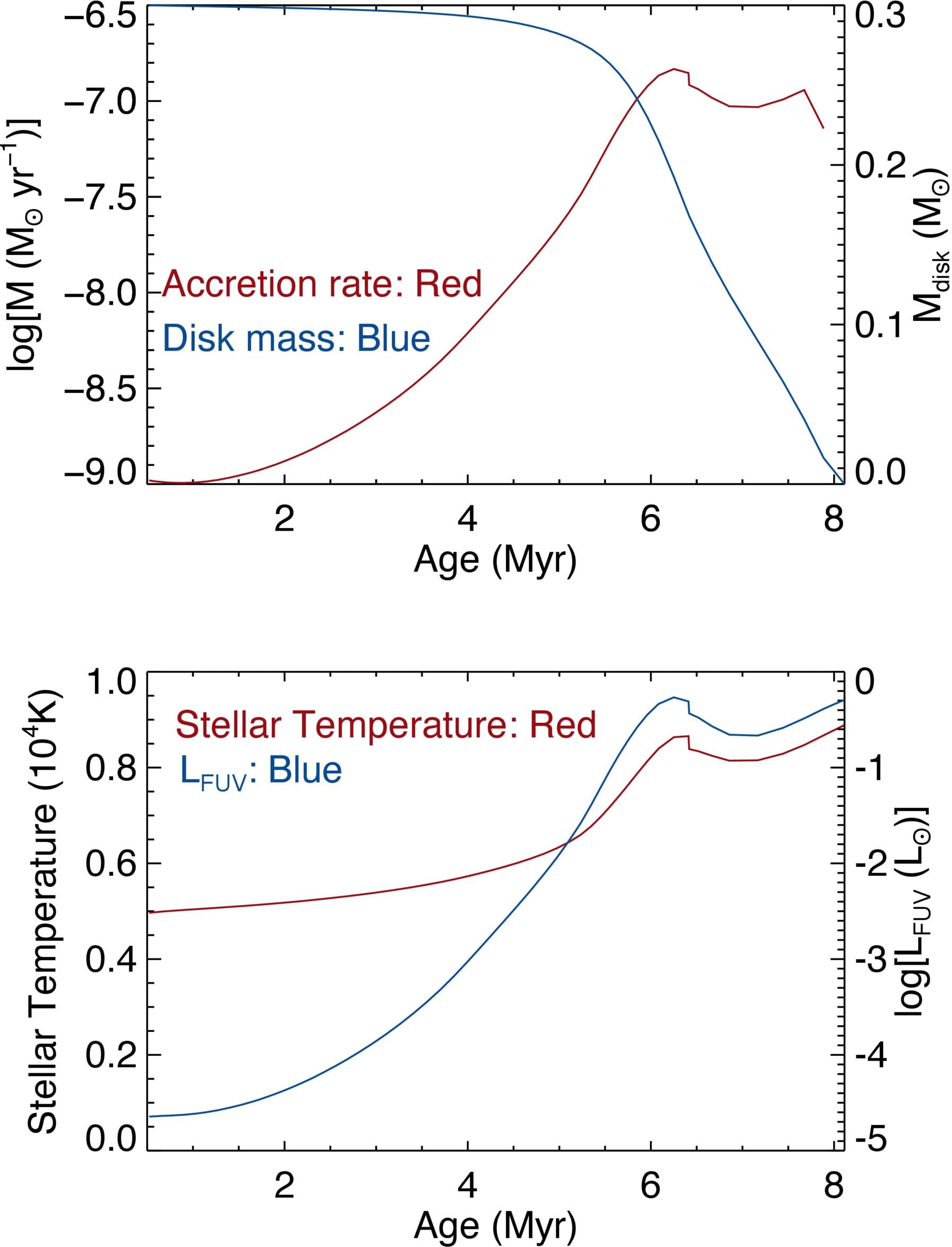

The researchers got to work on a model that could explain this. Their model shows that accretion is driven by some of the radiation from the star, the far ultraviolet (FUV) radiation. “We put forward a physically plausible scenario that accounts for the systematic increase of stellar accretion based on the increase of the effective temperature of the stars as they evolve towards the zero-age main sequence,” the researchers write in their article.

Here’s their solution: The more evolved Herbig stars are hotter than their younger IMTTS counterparts, and that greater heat makes the star emit more FUV. “Thus, the luminosity of the far-ultraviolet (FUV) radiation will increase by orders of magnitude. We propose that this increase drives a higher stellar accretion rate,” the authors explain. The FUV ionizes more of the gas in the disk, which creates greater accretion onto the star. This is because of magnetorotational instability (MRI), the primary force that drives accretion onto a star.

Stars are surrounded by their magnetic fields, and neutral gas doesn’t interact well with them. But ionized gas does. It responds to the magnetic field lines around the stars. When gas becomes highly ionized, it actually creates turbulence in the star’s magnetic field lines. The turbulence transports angular momentum outward from the disk. That means that the inner regions of the disk have weaker angular momentum, and that allows the star to accrete material more rapidly.

*These two panels from the research illustrate some of the results. The upper panel plots accretion rate and disk mass, and the lower panel plots stellar temperature and FUV emissions. Together, they show that the accretion rate rises with temperature and FUV emissions, even though the disk size shrinks. Image Credit: Brittain et al. 2025. AnJ*

*These two panels from the research illustrate some of the results. The upper panel plots accretion rate and disk mass, and the lower panel plots stellar temperature and FUV emissions. Together, they show that the accretion rate rises with temperature and FUV emissions, even though the disk size shrinks. Image Credit: Brittain et al. 2025. AnJ*

This appears to solve the problem of giant planets forming around intermediate mass stars. The increased heat of Herbig stars drives rapid accretion, and a more massive disk isn’t required.

“The understanding that hotter stars emit more ultraviolet radiation than cooler stars has been known for well over 100 years, and the expectations that the ionization of the disk plays an important role in the accretion process have been around for decades,” Brittain said. “This work epitomizes the relay race of scientific advancement by building upon these core ideas and showing that these systems indeed have an unexpected late growth spurt.”

These results also line up with modern observations of Herbig stars. Observations with ALMA and the SPHERE instrument on the Very Large Telescope show prevalent spiral arms in their disks. Different explanations were put forth for these spiral structures, including gravity waves, or perturbations by companions like brown dwarfs, stellar companions, or planets. But their less evolved IMTTS counterparts don’t have them.

In the conclusion of their research article, the authors write that “… spiral structure among Herbig stars is more plausibly a signpost of gas giant planet formation.”

“Finally, our model allows for disks with sufficient mass to form planets around Herbig stars to persist for several Myr, even at the high accretion rates observed in this evolutionary state, providing time for gas giant planet formation in these systems,” they conclude.