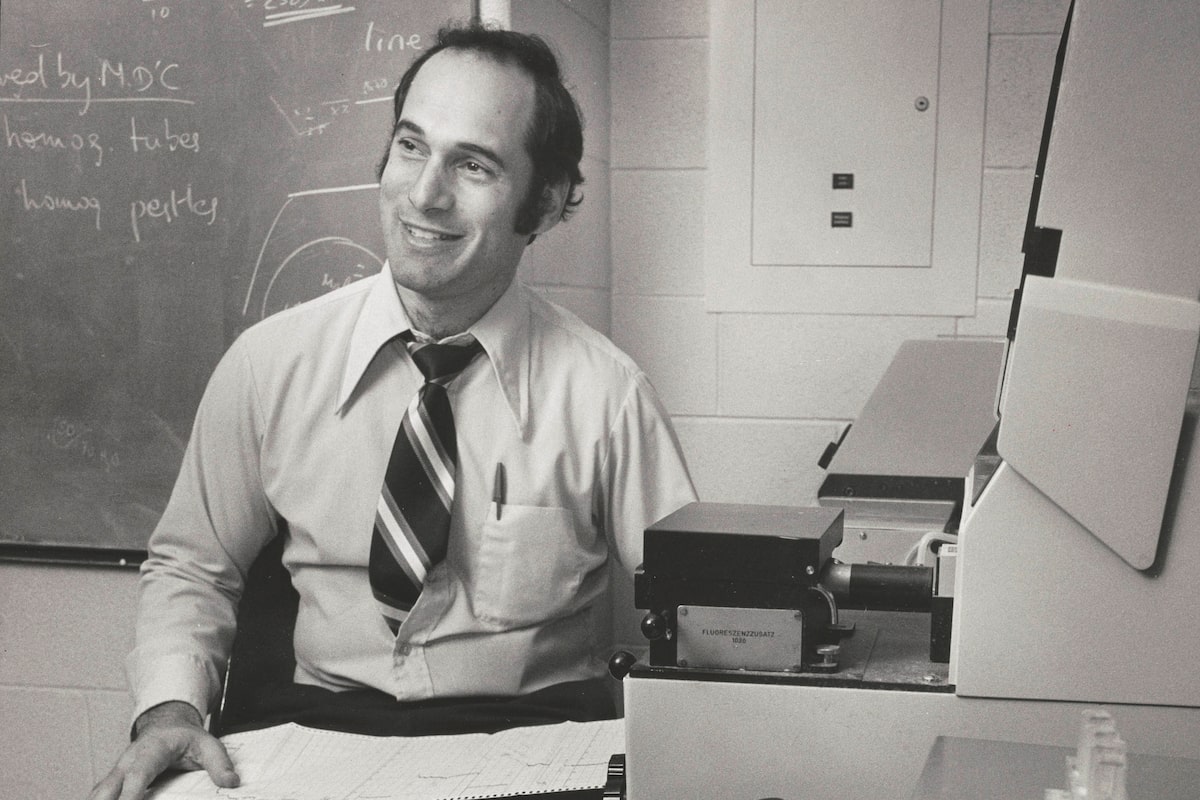

Researcher and teacher Mitchell Halperin worked in one of the more complex corners of medicine. As a nephrologist – kidney doctor – at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto for 50 years, he taught and conducted basic research on renal physiology related to fluid, electrolyte and acid-base homeostasis.

“He had an ability to put things in perspective, to put across concepts that were intellectually challenging. He could distill them down to their simple fundamentals, so even a child could see,” says Tony Fields, who learned from Dr. Halperin at St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto starting in the mid-1970s.

“He had this reputation as a star teacher,” he recalls. Dr. Fields went into oncology and what he learned from Dr. Halperin helped him deal with patient issues such as sodium imbalances. “The treatment of my patients was improved because I had been a disciple of his.”

Although he trained as a clinician, Dr. Halperin focused on teaching and research. He wrote or co-authored over 350 medical journal articles, 59 book chapters and 11 textbooks.

That included the book Fluid, Electrolyte and Acid-Base Physiology: A Problem-Based Approach, which he co-authored with his former research fellow and later St. Michael’s Hospital colleague Kamel Kamel. The book’s sixth edition is about to be published; Dr. Kamel says it has endured because of its practical approach.

Most of Dr. Halperin’s research looked at the nuances of renal physiology to better understand acid-base homeostasis.

“His special skill set would be to look at something and look backwards to the fundamental underpinnings of it, and sometimes see how there was a misconception. He could unravel things and envision a way to improve the current understanding,” Dr. Fields says.

“He was innovative in his thinking,” Dr. Kamel says. “I describe him not as somebody who was thinking outside the box, but somebody who was making the box. He always made sure to integrate his ideas into the overall picture.”

Dr. Halperin died on Nov. 5 at the age of 88. Many of the doctors caring for him knew of his professional accomplishments. “When he went into the hospital for the last time, I was speaking with the neurologist who was looking after him – so that’s not a kidney doctor. And he said he had three of his books,” says his son, Frank Halperin, also a physician.

While Dr. Halperin’s area of medicine related to the kidneys, it was really a whole-body, systemic and vital aspect of medicine, as dysregulation of the system could come from lung or heart problems, for instance.

Mitchell Halperin, centre, with his son Frank, left, daughter Aileen Halperin-Kozdas, centre-left, wife Brenda, centre-right, and son Ross, right, after receiving the Order of Canada.Courtesy of family

Dr. Fields nominated his former teacher and longtime colleague and friend for the Order of Canada; Dr. Halperin was named to the order in 2018. Dr. Fields wrote in his nomination letter, “It is impossible to estimate how many patients worldwide, suffering from serious disease or injury, have had their outcomes improved as an indirect result of Dr. Halperin’s career endeavours and achievements.”

Mitchell Lewis Halperin was born in Montreal on May 18, 1937, to Fannie (née Jacobs) and Mordechai Halperin, a dentist. He grew up with siblings Ruth and Alex.

While working as a counsellor at a camp outside Montreal, young Mitch would hang out at a local store. He was 18 when 16-year-old Brenda Geller went over to talk to him, thinking he looked lonely.

Not long after, when the two young people had become a couple, Mordechai approached Brenda and gave her his late wife’s wedding ring. Fannie Halperin had died recently, so he took it upon himself to let his future daughter-in-law know the family welcomed her. Mitch and Brenda married in 1958, when she was 19 and he 21.

He studied medicine at McGill University, graduating in 1962. (Brenda trained as a teacher, and later went into nursing.) Along with being a good student, he was athletic, playing hockey at a young age and competing in squash for McGill.

Dr. Halperin did a fellowship at Boston University and another at the University of Bristol, in biochemistry. By this time, the young Halperin family was expanding to include children Aileen, Frank and Ross, and they accompanied him as he finished his training.

Dr. Halperin joined St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto in 1968, enticed by the promise of being able to focus on research and teaching, without clinical care responsibilities.

“When people used to talk to him about patients, he’d say he just wanted the numbers. He didn’t need any other information, because the numbers spoke to him,” his daughter Aileen Halperin-Kozdas says. “He could change people’s lives just by figuring out what they needed. That was his super strength.”

Dr. Halperin’s approach was effective; he became a full professor in just seven years. At the hospital, he helped found the division of nephrology, serving as its head from 1998 to 2003.

Dr. Halperin and his wife Brenda ride a hydrobike at their cottage, also known as Skootamatta Lodge.Courtesy of family

Over his career, he earned what St. Michael’s Hospital estimated to be over 25 prestigious honours. That included the Order of Canada, honorary medical degrees from the University of Montreal and Université d’Auvergne Clermont-Ferrand in France, plus he was named a lifetime honorary member of the Royal Society of Canada and societies of nephrology in Australia/New Zealand and South Africa.

Dr. Halperin suffered a stroke in 2010, but kept working, officially retiring in 2018. He continued to do a little teaching and served as an honorary consultant.

While Dr. Halperin had a 50-year career publishing in high-impact journals, his son Frank says his biggest contribution was in training young clinicians and researchers. For these efforts he earned the American Society of Nephrology’s Robert G. Narins Award for teaching excellence, one of the accolades he was most proud to receive.

“He had a huge impact on people’s lives. People didn’t just go through his lab and leave. They stayed close, and he helped with their careers.”

The Halperins’ Toronto home had a basement room that housed many a friend, student, postdoc and visiting scholar. His children once counted the number of guests who had stayed in that room over the years, and it was up to 32 at one point – and they knew they had missed names. “They truly had an open-door type of home,” Aileen says of her parents, who similarly had many guests up to their cottage. “Everyone who worked for him became part of our family.”

Both the Halperin parents served as coaches for their children’s sports teams. Dr. Halperin would routinely flood the backyard to make a rink for chaotic hockey games full of kids and dogs.

“He wasn’t one of those hands-off kinds of guys,” recalls Frank, who remembers neighbourhood kids piling into the family station wagon to travel to games. (All three of the Halperins’ children went into health care, with Aileen becoming a nurse and Frank and Ross both doctors.)

“I was always so impressed by the time and quality of the family interactions that he had,” Dr. Fields says. “If I looked at my own work-life balance, it seems quite unbalanced compared to what he achieved while maintaining an international stature.”

Dr. Halperin leaves his wife, children, their spouses, and several grandchildren.

You can find more obituaries from The Globe and Mail here.

To submit a memory about someone we have recently profiled on the Obituaries page, e-mail us at obit@globeandmail.com.