The last time Jeff Axelbank spoke to his psychoanalyst, on a Thursday in June, they signed off on an ordinary note.

They had been talking about loss and death; Dr. Axelbank was preparing to deliver a eulogy, and he left the session feeling a familiar lightness and sense of relief. They would continue their discussion at their next appointment the following day.

On Friday morning, though, the analyst texted him to cancel. She wasn’t feeling well. Dr. Axelbank didn’t make much of it — over years of long-term psychoanalysis, each had canceled on occasion. But the following week, he still hadn’t heard from her, and a note of fear crept into his text messages.

“Can you confirm, are we going to meet tomorrow at our usual time?”

“I’m concerned that I haven’t heard from you. Maybe you missed my text last night.”

“My concern has now shifted to worry. I hope you’re OK.”

After the analyst failed to show up for three more sessions, Dr. Axelbank received a text from a colleague. “I assume you have heard,” it said, mentioning the analyst’s name. “I am sending you my deepest condolences.”

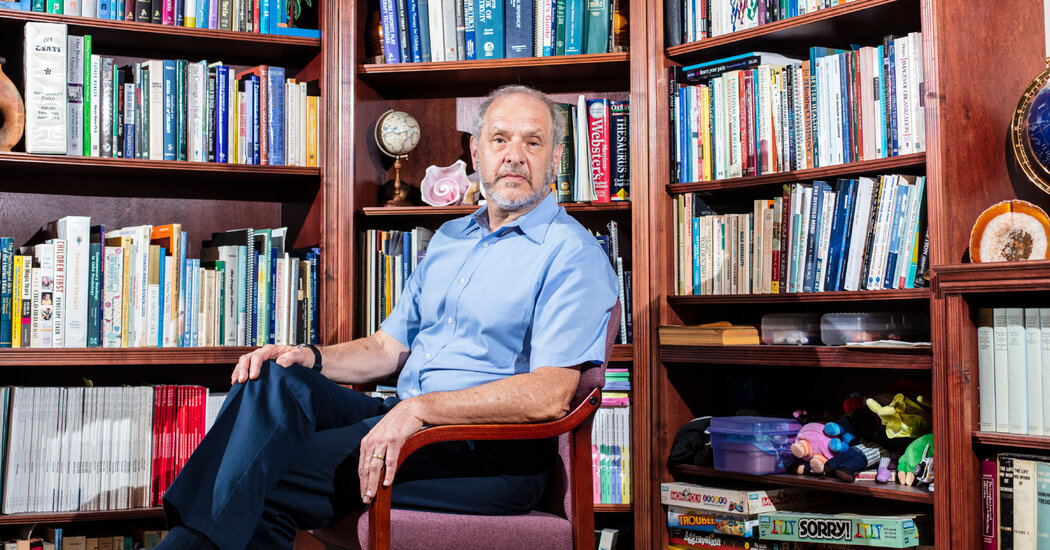

Dr. Axelbank, 67, is a psychologist himself, and his professional network overlapped with his analyst’s. So he made a few calls and learned something that she had not told him: She had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in April and had been going through a series of high-risk treatments. She had died the previous Sunday. (The New York Times is not naming this therapist, or the others in this article, to protect their privacy.)

Dr. Axelbank hung up in a state of shock — heartbreak, confusion, but mostly shock. He pored over their final conversations in search of signals he might have missed. He cycled through anger and self-recrimination. Should he have pressed her harder for details about her health? Did she think she was protecting him by keeping her illness secret?

He had encountered a thorny problem for those in the mental health professions. Ethics guidelines require psychologists to make preparations in case they become incapacitated or die, appointing an executor to break the news to their patients and find them new care.

But it is a chore that many of them push aside, and none of the major professional associations monitor compliance. Lynn Bufka, head of practice for the American Psychological Association, said she had no idea what percentage of members had a plan in place.

Even if that data were available, she said, pressure to comply would have to come from licensing boards or insurers, since, as she put it, “we cannot process an ethics complaint against someone who has passed away.”

As the mental health work force ages, a handful of activists within the profession are urging their colleagues to confront their own frailty and prepare patients for what is to come.

“Of course the patients are distressed when they lose their analyst, but the real anger and pain, about having been essentially lied to, is really quite awful,” said Dr. Robert Galatzer-Levy, who has published studies of patients whose therapists died during treatment.

Dr. Galatzer-Levy, 80, a senior analyst at the Chicago Psychoanalytic Institute, became interested in the subject after he was referred a dozen patients whose analysts had died. Often, he found, they were left traumatized, mistrustful of the whole endeavor of therapy.

Their analysts had been colleagues of his, well-respected and senior figures. But they seemed, he said, “around their own mortality to become really quite inept, and did not do obvious things, such as simply being straightforward with patients about what was going on.” Frequently, the patients learned about their death in the newspaper, or from a note attached to their analyst’s door, or through word of mouth.

“There’s a lot that therapists and analysts can’t do,” he said. “The one thing we can do is be honest. When one is basically being untruthful about something as important as whether one is going to be around to do the work — that is an enormous breach.”

‘She was kind of orthodox’

Dr. Axelbank, who lives in Highland Park, N.J., saw his analyst three times a week, settling himself on a plush brown couch while she sat behind him in an armchair. From the outset, she had turned a “laser-focused” attention on him, making it clear that she was fully devoted to his needs, a feeling he said he had never received from his mother.

Asked how the analyst made him feel, Dr. Axelbank searched for words, and finally retrieved a line from an old love song — “I’ve been waiting since I toddled / For the great relief of having you to talk to.”

The work with her changed him, he said. He no longer stutters. The “malignant, toxic” internal voice he had carried around since childhood was replaced by something gentler and more benevolent. It made him a better husband. It made him a better parent.

“I just lost the person who knows me better than anybody else,” he said. “Better than my wife, better than my family, because I’ve talked to her about everything. And so, to be without that is — it’s a terrible loss.”

And yet there was no shiva, no wake, no funeral. The week he learned of her death, he had a houseguest visiting, and he felt obligated to keep up a cheerful, lively demeanor. “We still had to walk the boardwalk, and play some Skee-Ball and go to the Phillies game,” he said. He compared her death to a miscarriage, or the death of a beloved pet: a profound loss that is unrecognized by society.

He was also angry. He couldn’t believe that she hadn’t told him. He tried to give her the benefit of the doubt: Maybe she needed time to come to terms with it. Maybe she was worried about hijacking their final months of treatment by shifting the focus away from his concerns. She was “kind of orthodox, old school,” he said, always brushing away his questions about her life.

But he also worried that maybe he was the one who screwed up, by allowing her to maintain that distance.

There was only one person in the world who he knew could help him untangle all these strains of dark feeling. And she was gone.

He found himself longing to return to her office, a place where he had spent some of the richest and most comforting hours of his life. From her couch, he looked up at a glass dream-catcher and a heavy, acorn-shaped lantern hanging from the ceiling. Maybe seeing those things one more time would help him let go.

“That makes it real,” he said. “They’re gone. You’re kind of putting all the pieces together.”

Other patients, recalling the sudden death of a therapist, described the same lack of resolution.

Eric Hensal, 58, a Washington-area political consultant, knew his analyst had cancer and had agreed to continue their sessions as his condition deteriorated. That wasn’t the problem. What bothers Mr. Hensal, 13 years later, is that no one called him when the analyst died. He found out when he showed up at his office for a session and the door was locked.

“No note, no nothing,” he said. “It’s just like, Oh, that’s it. You turn around and walk down the hallway and go to the elevator and leave. It’s sad. I mean, I still get sad when I think about it, because it was just so abrupt.”

Meghan Arthur, 45, has played and replayed her final exchanges with her analyst. The analyst’s cancer was not a secret — for months, they scheduled their sessions around her chemotherapy. But the analyst told Ms. Arthur she was going to beat it. She talked about the future, maybe renting a cottage in Scotland to plot out the next stage of her career.

It was confusing. Toward the end, the analyst sent a warm, affectionate note to all her patients, explaining that she was going to a hospice — but only for the weekend. “If we can get an appointment on the calendar, we should do it, and then see how things pan out,” the analyst wrote. “One never knows.”

Then a week passed, and another week, and Ms. Arthur got a terrible feeling in the pit of her stomach. “I wanted to trust her,” she said. “And I don’t think she was lying. I think that’s what she really believed.” Three weeks after her last appointment, a family member shared the news that the analyst was dead.

Years have passed, and Ms. Arthur has not quite shaken off a feeling of abandonment. “This woman helped me so much, for so long, and then, at the very end, she couldn’t be clear to me about what was actually happening,” she said. “She kind of put that on me — which is not, I mean, as the patient, that is not supposed to be my job.”

An honor system

In 1999, a prominent young San Diego psychologist died suddenly, leaving her family to manage a legal and logistical nightmare: reams of sensitive case files and an appointment book full of long-term patients who had to be informed of her death right away, lest they simply appear in her office to find her gone.

Her colleagues at the San Diego Psychological Association, agreeing that this should not fall to her family, divided the work among themselves. Soon they had a template for a “professional will” — a document identifying executors and the steps they should take to terminate a practice.

The idea spread quickly, and it began to appear in professional ethics codes. But writing a will made many members uncomfortable, said Linda Altes, who served on the association’s PRID committee, which stood for Psychologist Retirement, Incapacitation and Death. (“We just shortened it and hoped nobody knew what we were referring to,” she said.)

“Just getting people to write an acknowledgment that it could happen, that was quite an accomplishment,” she said. And it remained, as she put it, “an honor system.”

Robyn Miller, a therapist in Bethesda, Md., began studying the problem seven years ago, after she served as an executor for a colleague and close friend who died of cancer. She was taken aback by the emotional intensity of the task, she said, counseling “patient after patient who was shocked and bereaved,” and some who felt “rejected and abandoned.”

And she began to doubt that the honor system was working. When she surveyed 114 colleagues, they agreed overwhelmingly that a professional will was a good idea — but 68 percent of respondents did not have one. She began to compile accounts from patients who learned of a clinician’s death in unsettling or impersonal ways.

“It’s really because we are human, too,” Dr. Miller said. She concluded that therapists could benefit from the services of a professional executor, much as they outsource marketing or accounting. Last year, she started TheraClosure, which steps in after a clinician’s death to manage records and counsel patients. Doing so swiftly and sensitively, she said, could be “the difference between loss and traumatic loss.”

And it is true: The way a patient learns of a therapist’s death seems to make a difference. Laura Robinson, 56, a psychologist in Ann Arbor, Mich., spoke warmly of how her own therapist had handled it.

When the therapist went into hospice, she delivered the news in a long, personal letter, recalling specific things about Dr. Robinson and the time they had spent together. Dr. Robinson was so moved that she spent two weeks composing a response that “really conveyed what she meant to me.” When she sent it, it bounced back.

“I know she knew the things that I said in the letter anyway,” Dr. Robinson said. “It was out in the universe.”

When Leilani Crane received word that her therapist had died, she was in the middle of moving, and a ring — something she had long ago given up for lost — had dropped out of a drawer and bounced on the floor.

It was clear that the therapist had prepared for this moment. The colleague calling on her behalf seemed to have plenty of time to talk, offering help with referrals and inviting Dr. Crane to attend the funeral. She remembers listening and gazing down at the ring, whose reappearance felt supernatural.

“The fact that she was thoughtful enough to do all this, and take care of us, in case she died,” she said. “Really, really, I didn’t expect it.”

Returning to the scene

As the shock of his analyst’s death wore off, Dr. Axelbank found himself thinking about systems. He began seeking out other patients who had lost their therapists and might want to form a support group. He prepared a workshop for psychoanalysts, challenging them to overcome their resistance to speaking about their own death.

“You have to analyze the resistance,” he said. “Just wagging your finger at people and telling them you shouldn’t do this doesn’t work.”

He also wanted something more personal. He worked the phones, and eventually found the analyst’s sister. He asked if he could visit the office one last time.

A few days later, he stepped into the analyst’s waiting room and took a seat.

“I’m here,” he texted, and two women — the analyst’s sister and mother — came out of the office. He registered the fact that they looked like her. It would have appalled the analyst, he thought, this demolition of therapeutic boundaries. But there they were, sitting in the analyst’s office together, looking at her baby pictures.

“All of a sudden, the curtain has been drawn back,” he said.

Her death had not come out of the blue, they told him. In April, she had been diagnosed with “very advanced” Stage 4 cancer. She was losing weight, and took pain medication when she saw patients. But she did not consider stopping work, her sister said. She had sessions scheduled on the day after she died.

“I think I was the one who said, ‘So she was in denial?’” he said. “The word her sister used is that she dove into her devotion to her patients.”

They meant it kindly — as evidence that she cared deeply for her patients — but Dr. Axelbank felt his anger flare again.

“She deprived me of saying goodbye,” he said. “And to tell her how much I love her, and what she meant to me.”

They handed him a stack of records, the analyst’s notes from five years of sessions. He asked if he could take an object, the dream-catcher that the analyst had hung near the window, and they gave it to him.

The two women left him alone in the office for a few minutes, and then it was done.

Before he walked out the door, Dr. Axelbank asked his analyst’s mother if he could give her a hug. They clung together, and, for just a moment, he felt the analyst was back in the room.

Audio produced by Adrienne Hurst.