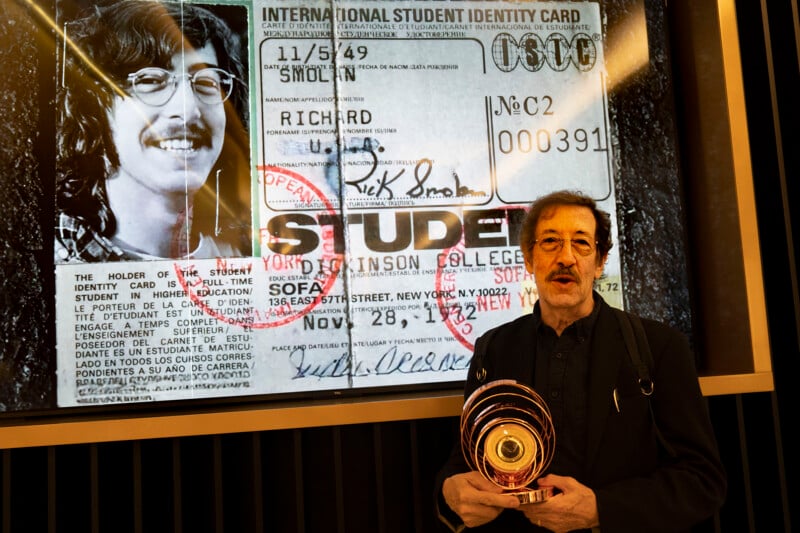

HIPA, the world’s most lucrative photo contest awarding $1 million in total prizes annually, announced its 2025 winners on November 11 in Dubai, the popular business and tourist destination in the United Arab Emirates. The Photo Appreciation Award of $100,000 went to photographer, film producer, and best-selling author with five million books in print, Rick Smolan.

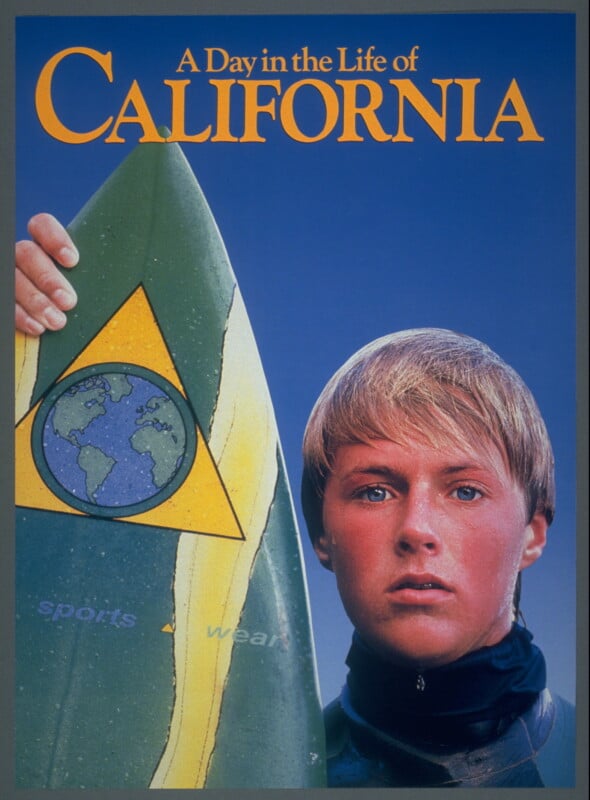

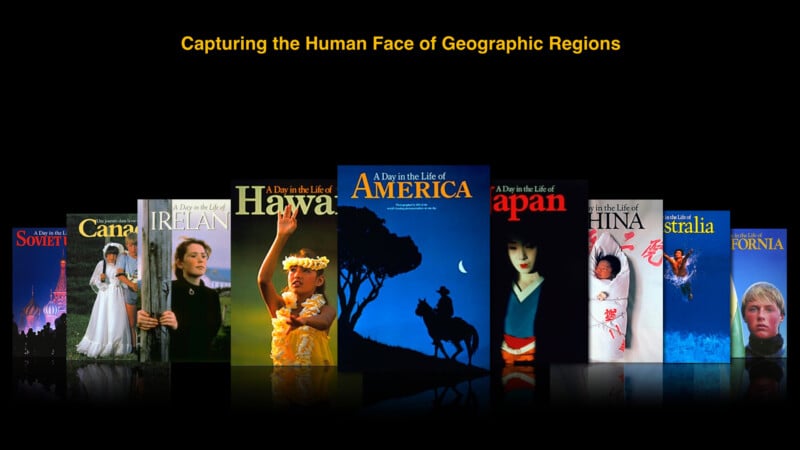

Rick Smolan is a former photojournalist for Time, Life, and National Geographic. When Smolan’s name comes up, it is usually associated with the A Day in the Life Book series, which gave a significant boost to the mass-market coffee-table book industry. He has published 80 books, eight of which have landed on The New York Times Best Seller list.

A Half-Frame Camera and Elliott Erwitt for Inspiration

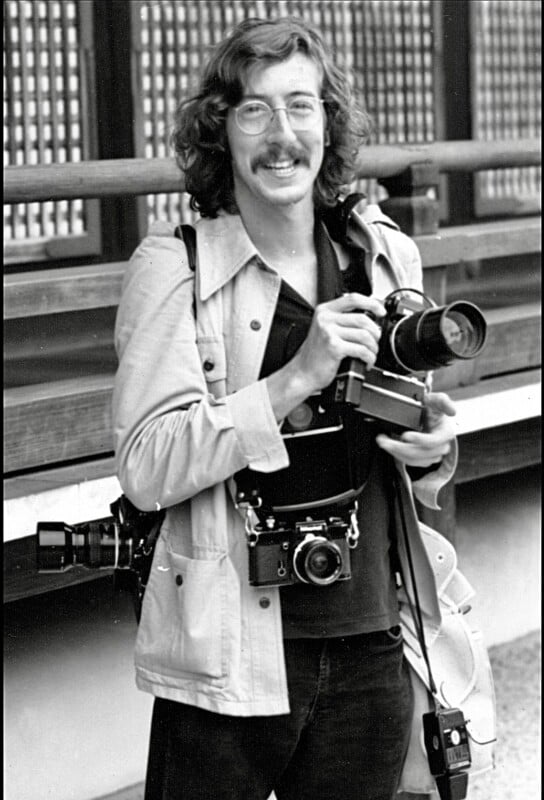

Smolan’s pursuit of photography unfolds almost like a movie, from the moment his father forbids him from pursuing a photography career. However, he did present him with a Minolta Repo-S (a rare model of Minolta’s half-frame cameras in the 60s with a fast f/1.8 lens) when he was sixteen.

“I lived in Spain for a year with a family,” begins Smolan as he narrates his almost five-decade-long photographic career to PetaPixel. “I didn’t speak a word of Spanish. They didn’t say a word of English. They just drop you into a family, and then you figure it out. And I started taking pictures of my classmates and selling them copies to afford the film. I could talk to girls [with the help of my camera] for the first time, which is very important when you’re 16, because I was very shy. I learned how to develop my film and how to print pictures.

“My dad [also] gave me a book of photographs by Elliott Erwitt (PetaPixel’s last big interview of Erwitt a year before he passed away) when I was 16. They [the pictures] were funny, quirky, and amusing. They were not mean, but he was obviously amused by humanity. They allowed you to write your own captions. So, as the artist invites you into their world, you get to participate in the meaning of it.

“And I, even as a 16-year-old, was so attracted by that, and that’s what I wanted to do with my pictures. I was just hooked. It was just all I wanted to do–take pictures and develop them.”

Seeing his fascination with Erwitt’s imagery, Smolan’s father called Erwitt’s office and persuaded them to offer him a summer internship. But he refused to go, saying he wanted to be a professional photographer first before meeting Erwitt. Little did 16-year-old Smolan know that one day Erwitt would become his father-in-law and contribute to his books.

“My dad was furious,” remembers Smolan. “He screamed, ‘You will never be a professional photographer. You’re going to be a doctor or a lawyer. Photography is a hobby. It’s not a profession.’ I said, ‘Well, it’s a profession for Elliot,’ and my dad said, ‘You know, you have a D minus average. You never finish anything. You have this crazy idea that you’re going to work for some magazine like National Geographic or Time. It doesn’t work that way. I’m not sending you to college to do baby pictures and weddings’.

“He [Smolan’s father] wouldn’t let me go to any college with a photography program. So, in the first week of college, I went to my art professor, Dennis Aiken, [the head of the art department at Dickinson College], and asked if I could create my own photography major. He was kind of amused.”

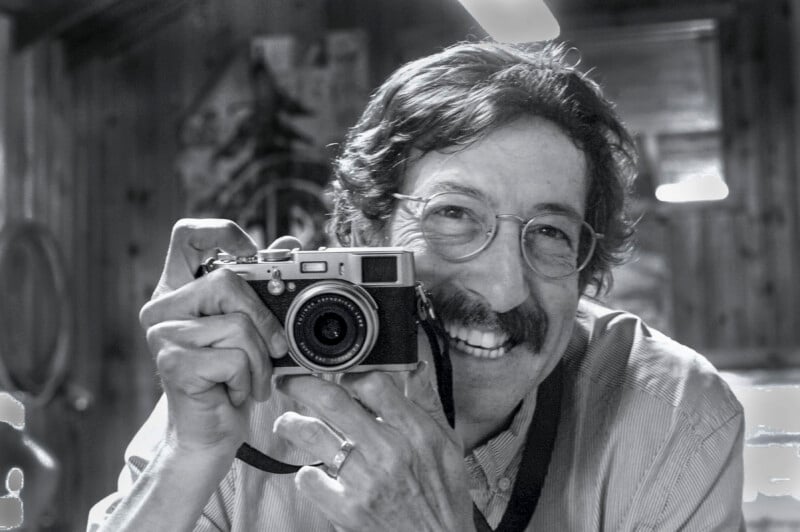

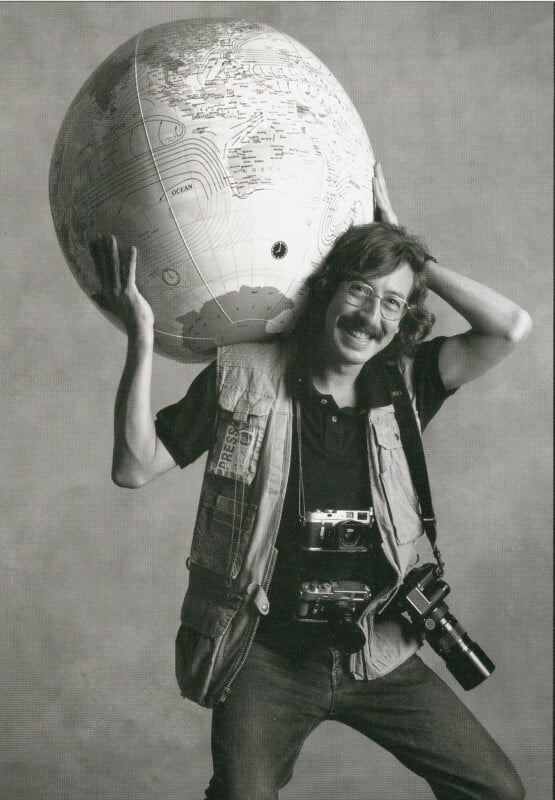

Pic by Phil Mistry

Pic by Phil Mistry

But the wise teacher, seeing his enthusiasm, let the student have his way. When the professor saw that young Smolan was a self-starter in photography, he introduced him to Jack Corn and his wife, Helen, who ran a stock photo agency in Tennessee.”

Learning the Ropes of Photography through a Stock Photo Agency

“What’s a stock photo agency?” asked the student. “The professor said, ‘Well, all these pictures you’re taking for the yearbook and for your classes, you put a box of 100 pictures together, you send it to them, and they sell your pictures for you.

“So, I sent a box of pictures to Helen and Jack, and to my astonishment, they started sending me checks for hundreds of dollars, which in the 70s was like 1000s of dollars now, and when I graduated, Jack said, ‘I want to introduce you to the picture editor of Time magazine, John Durniak’ [after 8yrs he joined NYT as picture editor in 1981].”

“And so, I went up to New York City with my yearbook and my box of prints, and John said, ‘I love your work. You know. Love to give you some work.’

“I walked out of the office, and a guy was sitting there who introduced himself as David Burnett. And he goes, ‘Can I see your work?’ So, I showed him my pictures, and he said, ‘Are you with an agency? And I said, ‘Like a Stock Photo Agency?’ He said, ‘No, like a photo agency like Magnum, Sigma, Gamma, or Sipa. I said, ‘I don’t know what that is.’ He goes, ‘Well, there are photographers that gather into these agencies, and they get you work, and they take 50% of your income.”

“I Don’t Want to Give 50% of My Income” to a Photo Agency

“I said, ‘Well, I don’t want to give up 50% of my income.’ And he says, ‘Well, the reason it’s worth it is that they get you assignments, they edit your pictures, and you go on to the next job, and they do all the back-end stuff. They bill and chase people who don’t pay you. And so, he said, I’m forming a photo agency [Contact Press Images] and we have Annie Leibovitz, Doug Kirkland, Eddie Adams, John Franco, Gorgoni, Alon Reininger, and Dilip Mehta. We’re looking for a young photographer to do the assignments that we don’t want to do. And I said, ‘What does that mean?’ He goes, ‘Well, when a magazine offers us a job, we don’t want to say no, because we want to keep the jobs coming. But sometimes, to be honest, some of the jobs are not very interesting. And he said, we’re looking for a young photographer who will. And I said, ‘Look, I’ll do anything. I’m happy to take the, what do you call it? The outtakes, the rejects.’

He said, ‘Well, Pan Am has a press junket. It’s the first nonstop flight from New York to Tokyo, lasting 18 hours. You get off in Tokyo. You photograph two guys shaking hands. You get back on the plane and fly back to New York. You want the job? It’s like 30 to 36 hours of flying.’ I said, ‘When I get to Tokyo, can I get off the plane?’ He goes, ‘Yeah. I mean, if you want to pay for it yourself. There’s no money to pay for hotels. But if you want to enterprise, sure.’ So, I left on a Monday, told my sister I’d be back on a Friday, and I came back 11 months later.”

Assignments Kept Flowing When He Stayed Over in Japan

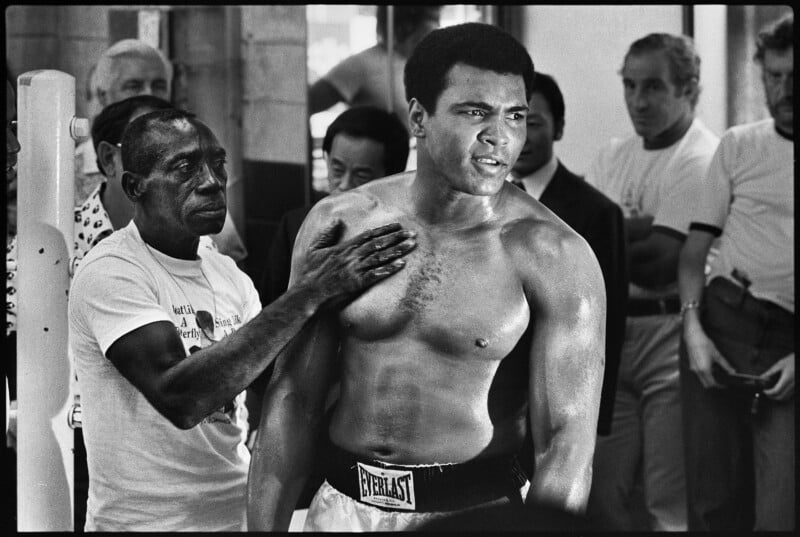

“Once I got to Japan, I was like a pig in shit,” remembers Smolan. “When Time magazine found out that I was in Japan, [Burnett spread the word that they had a photographer based in Tokyo], they said, ‘You want to go live with the Tokyo police force for a month for Time Life books?’ Then Muhammad Ali came to Japan to fight a wrestler, and so I ended up photographing that event. After that, the typhoon hit Guam [U.S. island territory in the Western Pacific], so Time flew me there.

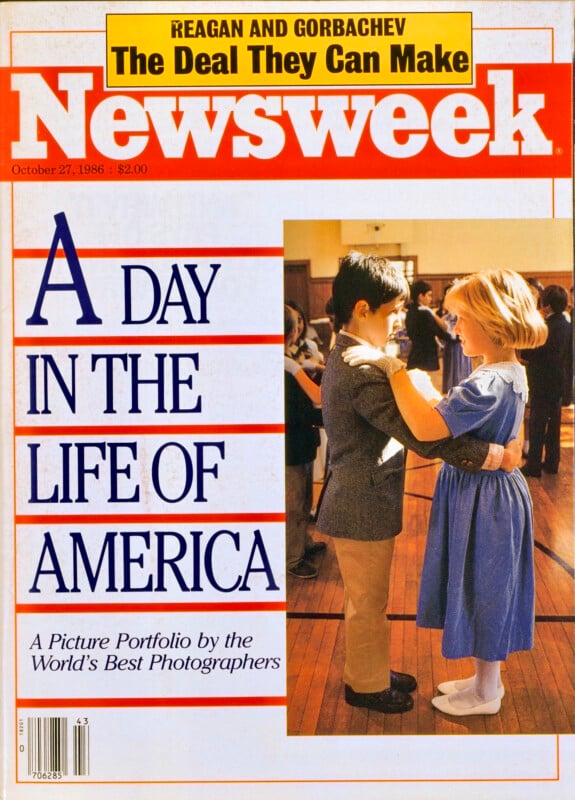

Some of the many TIME covers shot by Rick Smolan

Some of the many TIME covers shot by Rick Smolan  Muhammad Ali in Japan to fight Japanese professional wrestler Antonio Inoki for TIME magazine- Pic by Rick Smolan

Muhammad Ali in Japan to fight Japanese professional wrestler Antonio Inoki for TIME magazine- Pic by Rick Smolan

“The Prime Minister of Australia [Malcolm Fraser] came to Japan to spend a week before he went to China, and so Time assigned me to spend a week traveling with the prime minister. I had hair down on my shoulders. I didn’t look like the rest of the press corps. I was this hippie kid. I looked like I was 15. And we toured the Nikon factory as part of his trip. And that afternoon, we were taking a bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto, and the Secret Service came back to the press car and said, ‘Where’s the American kid?’ And I raised my hand, and all the other journalists said, ‘Oh, you’re in trouble now, mate.’ The Secret Service said ‘The Prime Minister wants to speak with you.’ And I said, ‘Oh, shit. What did I do?’

Pic by Ridk Smolan

Pic by Ridk Smolan  Photo by Rick Smolan

Photo by Rick Smolan

“They escorted me to a little private compartment, and they closed the door, and he said, ‘So do you prefer the 28 NIKKOR or the 35mm?’ And he was like a closet photographer. He said, ‘I’d always wanted to be a photographer.’ His parents made him go into politics. And, of course, I immediately told him my story.

And he said, ‘Have you ever been to Australia?’ I said, ‘No, I would love to go.’ And he said, ‘We have a program where the Australian government brings six journalists a year at the government’s expense, and we tour you around the country for two weeks. Would you like to come as my guest?’ So, it was like, Oh, my God, of course. I would love it. And he said, ‘Would you do my Christmas card for me?”

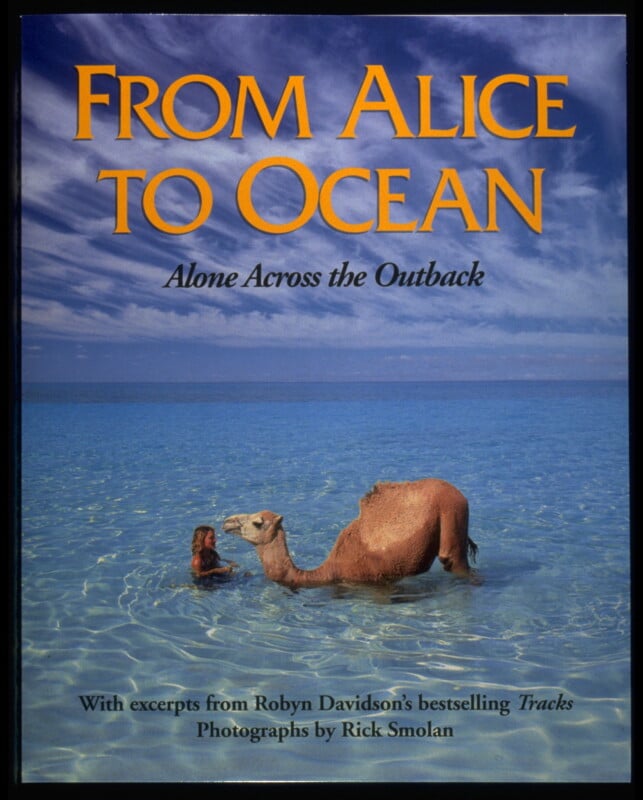

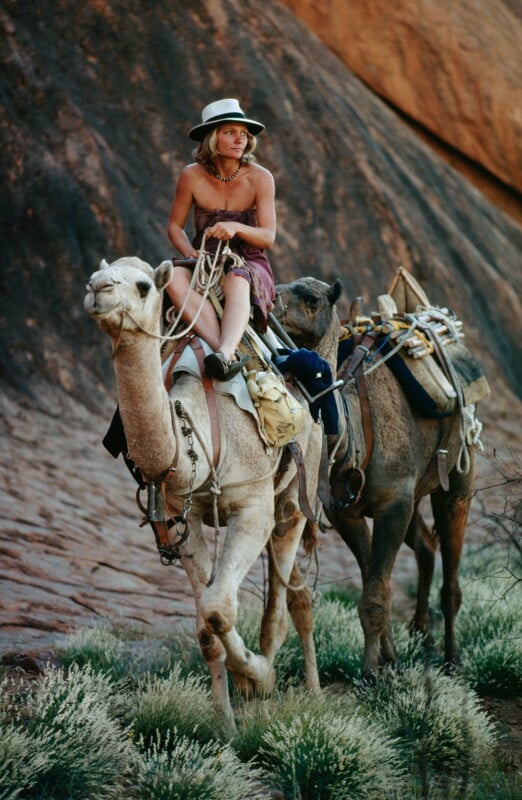

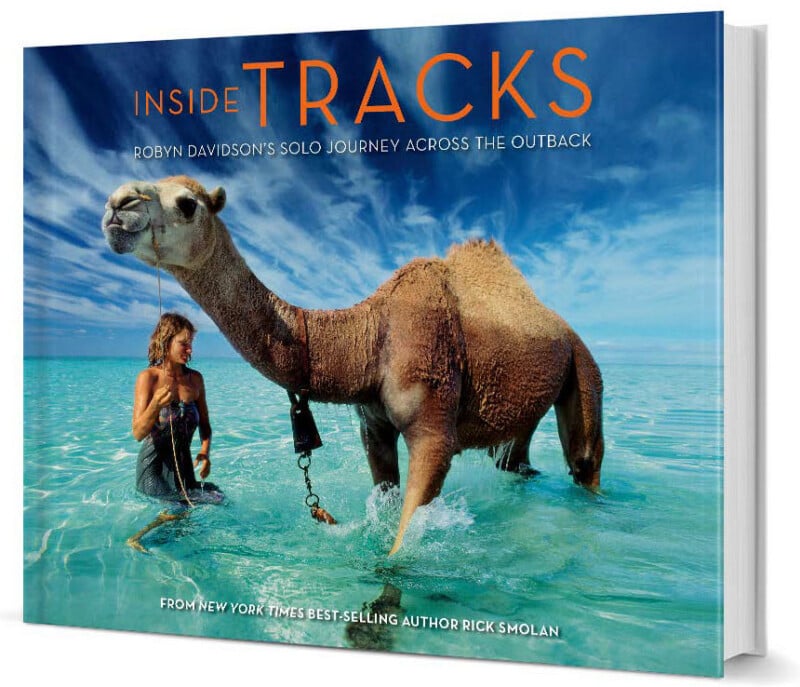

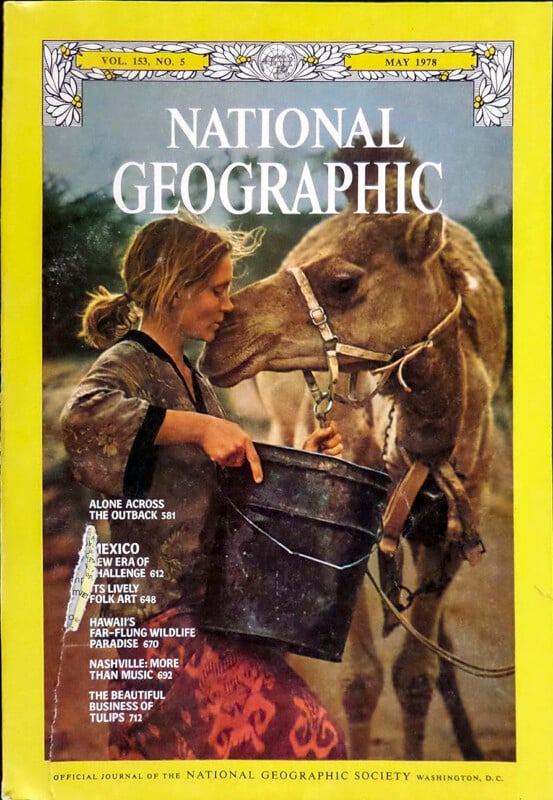

From Alice to Ocean (1,700 Miles through a Desert with Camels)

“When I got to Australia, I told Time the Prime Minister flew me there,” says the photojournalist. “Of course, they’re in heaven because every magazine wants one of their journalists to have it in with a politician. So, Time said, ‘Well, since you’re in Australia, we want you to shoot a cover story on Aboriginal people for us. Roy Rowan, the writer, said, ‘Here’s a woman that you can talk to who took me into the Aboriginal camps to get permission to meet the tribal elders.

“So, I fly to Alice Springs [in the center of Australia] to meet this woman, a fixer. [I messed up directions to the meeting], and the most beautiful woman I ever saw in my life was washing windows. I was 26 years old and had three cameras around my neck. This girl was gorgeous. And so, I lifted my camera and took some pictures of her. She started screaming at me, like, ‘Put your f**king cameras down. Who the hell do you think you are?’

“And Burnett and other photographers had always said, if people get angry at you when you photograph, never slink away. Always walk over, apologize, and put them at ease. Because it’s good, photographic hygiene. So, I walked over, I said, ‘I’m so sorry. The light was so beautiful. You were backlit.’ I made up some bullshit.

“And she said, ‘Oh, you’re American. You f**king parasites come in here every week. You take advantage of these people. You get paid hundreds of dollars a day to photograph their misery, and then you leave them to their misery.’ I couldn’t calm her down. She was so angry at me, not just for taking the pictures but because I was a journalist. She was angry because I was American. She was angry because I took her picture. Nothing, I said, could calm her.”

Smolan finished his assignment on Aboriginal people with help from his fixer, who then invited him to dinner at a house where people in the Aboriginal rights movement were meeting. On landing at the house, Smolan, much to his chagrin, was greeted at the door by the same window-washing woman he had had a dispute with.

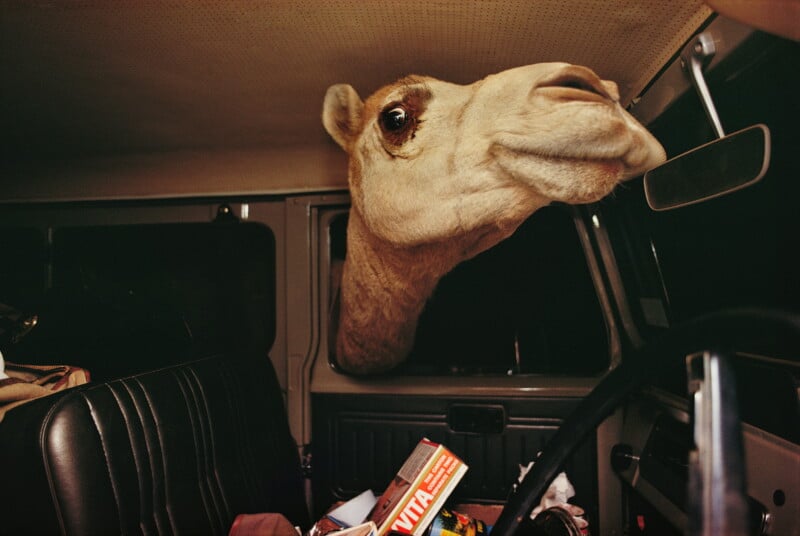

There were camels tied to the back of the house, and Smolan inquired with fixer Julie what they were doing there.

“She [Robyn Davidson] has this crazy idea,” said Julie, “that she’s gonna walk 2,500 kilometers from here, through the Gibson Desert, out to the Indian Ocean. We told her we want to go with her. She won’t let anybody come. She’s very private, and she’s been working on [it, while] waiting on a**holes at pubs and washing windows.

“Robyn wants to ask you a favor,” was the surprising thing Julie said on the last day before leaving. “She wrote to National Geographic a year ago and asked if they would give her some money to underwrite her trip. They never even answered. And she thought, maybe you might know somebody there. Could she use your name?”

“I was at a workshop with Bob Gilka, who’s the director of photography,” replies Smolan, “but I don’t know if he remembers me. I was one of like 25 young aspiring photographers. She can use my name, but I don’t really know if it’ll help.”

In the next four months, Smolan shot four Time covers and NYT Magazine assignments, then flew back to the States after 11 months. Three days later, the phone rings, and it is Gilka, asking whether the camel lady is serious about her trip, as they were considering a sponsorship. They didn’t want the headline, ‘National Geographic subject dies in week two.’ Smolan assures Gilka of her seriousness and immediately lands an assignment to cover her adventure through the Australian outback.

Pic by Phil Mistry

Pic by Phil Mistry

Smolan flew in five times during the course of a year to photograph her, and to this day, it is the most memorable assignment he has done. Smolan told me the whole story for more than an hour at The Sheraton in Dubai while he was there to collect his Photography Appreciation Award from Hamdan International Photography Award (HIPA), founded in 2011 under the patronage of the crown prince of Dubai, Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum. The story was so engrossing, even though I knew parts of it, that I did not dare interrupt Smolan as he kept going.

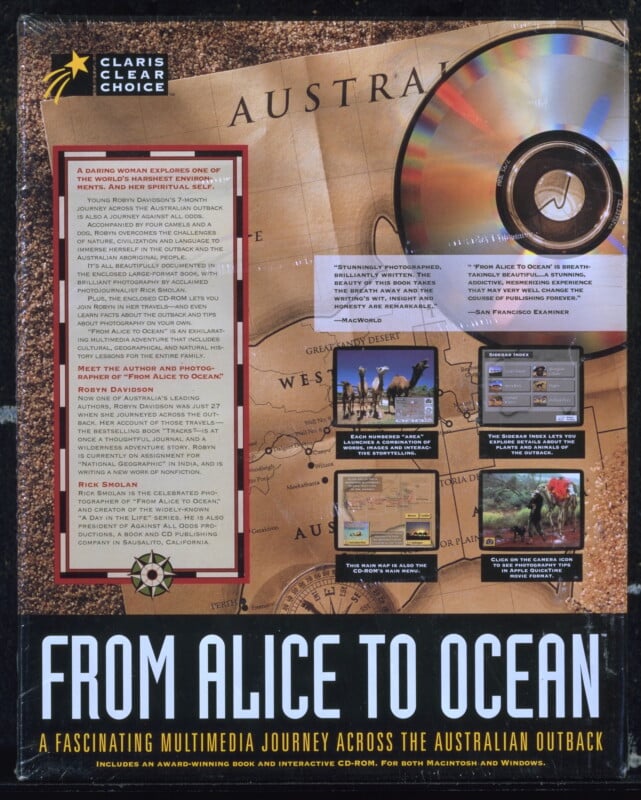

The Camel Lady, Robyn Davidson, with her beloved dog, Diggity [Davidson rescued her from medical research experiments], and four camels, trekked 2,700 kilometers [1,700 miles] across some of Australia’s most remote and inhospitable deserts, from Alice Springs to the Indian Ocean, in 1977.

Smolan found himself continuously butting heads with Davidson on what she wanted and did not want during the trip, which was affecting his photo assignment. But there were pleasant moments too, and at the end of it all, Smolan, who “had this attraction to crazy women in my 20s,” and Davidson were a couple.

The photo assignment story almost reads like a Hollywood movie. Not almost, but it was an actual Hollywood movie, Tracks (2014, 83% Fresh on Rotten Tomatoes), in which Adam Driver plays Smolan, and Mia Wasikowska plays Davidson.

More than Plain Reporting: Illegitimate Children of American GIs

“Robyn said to me, when we’re still in Australia (much later on the set of the movie after she had broken up with Smolan), now that my trip is over, are you going back to being a prostitute?” startling Smolan. I said, ‘Really, you’re still doing this to me?’ She said, ‘No, I mean this in a good way.’ Smolan queried, ‘What part of calling me a prostitute do you define as good?’ She said, ‘Rick, until my trip, somebody would call you, Time would call you, GEO would call you. Here’s a story we want you to shoot, and you’re like a hired gun, right?’

“She said, ‘I feel like my trip was the first time you put your career and your ego aside, and my question is, are you going to find something where you can use your skills as a photographer to change the subject? You had a big impact on my life. You were part of this trip. You weren’t just documenting it. My question is, are you going to find something else you can actually change, rather than just be a parasite feeding on it?’

“So, I found out that there were 40,000 children stranded all over Southeast Asia who American GIs had fathered [The Story of a Girl-TED Talk]. In every place where the United States has had a military base, there were illegitimate children of these GIs. And the local government says these are the children of GIs. And the American government says, they are children of prostitutes or, you know, they’re not ours, it’s not our responsibility. The military knew all about this. They actually had signs in Korea that said these were the 10 bars where you were most likely to get VD [ older term for sexually transmitted diseases]. They would inspect the houses where the guys live with the girls. So, the military was completely aware of this. Obviously, they were, but they would take no responsibility for it.

An Amerasian girl with her grandmother in Korea

An Amerasian girl with her grandmother in Korea

“I had made a lot of money. Robyn’s trip appeared on 40 magazine covers after the Geographic, and after three months, you get the rights back. So, Contact sold the pictures worldwide. I made a fortune from then. I always gave half of everything I made to Robyn. I still do, even today, when people buy the pictures, half of the money always goes to Robyn. So, I decided to take my half of the money and found six children in different countries. My idea was to spend six months traveling and photographing their lives. And I had this idea. I was going to solicit American magazines and send a copy to every member of Congress, every senator, and every mayor, blah, blah, blah, to try to raise awareness.

I went to many different American magazines, and nobody would touch the story about illegitimate American GIs’ children. So, I went to GEO magazine [originally from Germany], which said, ‘We love this story. It’s so powerful, it’s so important, it’s a cover story.’

“So, I worked with them for months. I helped them find a writer. The whole thing was laid out, and I approved everything; all the cover pictures and the opening spread. I left for an assignment, called back in to check the captions just before it went to press, and was going over all the captions when… [Smolan realized that they had removed all the incriminating photos, citing low circulation and the fear of risky articles hurting them].

Smolan was furious as he had worked two years on the story on his own dime.

“Give me back the story,” he screams. “I’ll go somewhere else with it. They said, ‘We’re going to press tomorrow. It’s too late to pull it.’ I said, then take my name off the story… It’s an embarrassment. They said, ‘If you take your name off the story, we’ll drop it as a cover story, and you’ve hurt the kids even more.’ I said, ‘F**k you.’ So, they took my name off the story and dropped it as a cover.”

Cutting Out the Photo Editor to Have Your Own Voice

“I realized, you know what?” reflects Smolan. “It doesn’t matter how good a photographer I am. I will never have any control over the finished product. I’m always going to be a cog in somebody else’s machine. So I was sitting in a bar in Bangkok with Philip Jones Griffiths, JP [Jean-Pierre] Laffont, Burnett, and others. And I was so upset, and we all were. Everybody’s telling their story about how much they hated their editors and how betrayed they felt.

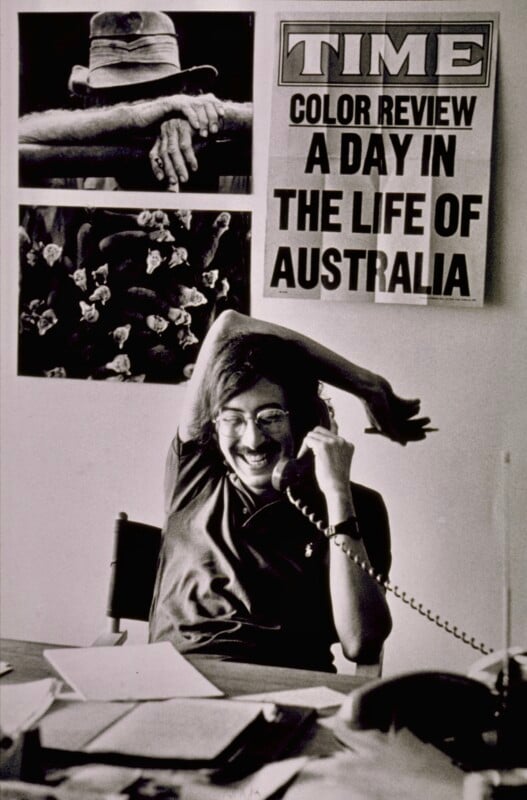

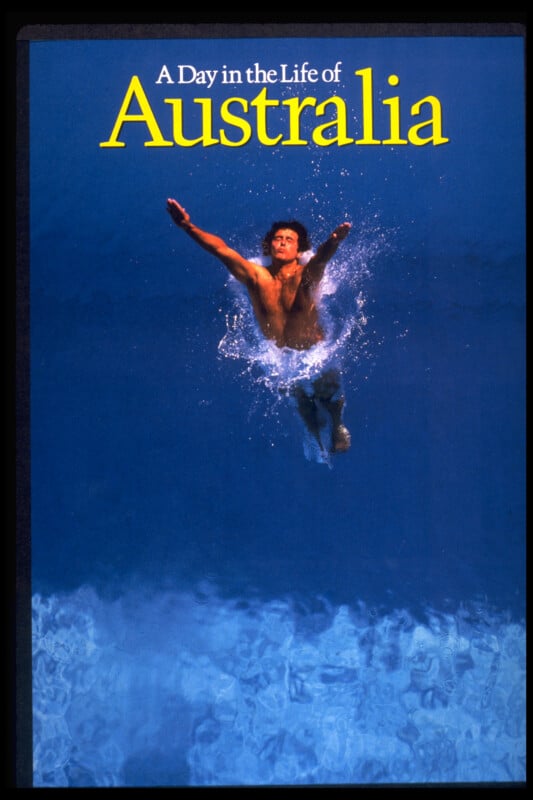

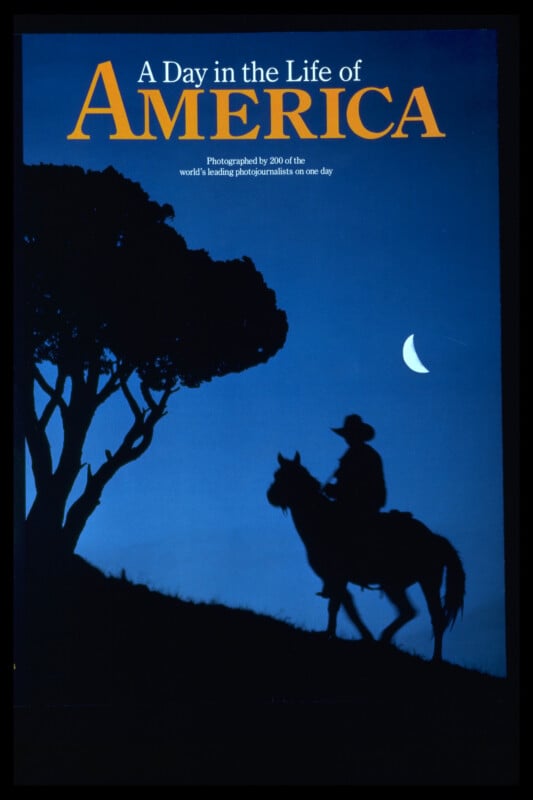

“And I said, ‘You know what, we should all do a book ourselves with no f**king editors. You guys are always asking me about Australia. We should do a day-in-the-life of Australia. We should bring like 30 photographers and do the Olympics of photography. And no editors, just photographers,’ and so all my friends at two in the morning in Bangkok, blowing off steam.

“Okay, Rick, you go organize it, and we’ll all come, they chanted. For them, it was just a random conversation. For me, I was so disillusioned with journalism. So, I met with 35 publishers, all of whom laughed me out of there.

“Because the Prime Minister of Australia had been so kind to me, I went back to him and said, ‘Look, you brought me to Australia. Could you bring 100 photographers to Australia?’ And he said, I don’t have that kind of budget. But I’ll help you. I’ll set up meetings for you with the CEOs of Qantas, Kodak Australia, Hertz Australia, Hyatt Australia, Steve Jobs, and you ask them for free airline tickets, computers, film, hotel rooms, and cars [for your project].

And then came the surprise—the Prime Minister wanted to be one of the 100 photographers. Smolan originally had misgivings about any “selling out” to big brands, but it all worked out in the end, and the book was a success.

“Our sponsors all ran full-page ads saying they were so proud to be the official airline or film, and we suddenly had multimillion-dollar ad campaigns,” smiles Smolan. “If a publisher had said yes to me, I would have made 50 cents a book. I would have done one book and gone back to shooting, but here I had learnt how to publish, publicize, and market it.

“Then the Governor of Hawaii came to Australia, and somebody gave him a copy of the book, and his staff called us and said, ‘Our 25th anniversary is coming up. The Governor wants to know if you’ll come and do [a book for] us.’ And then American Express called and said, ‘We’re fighting with the JCB card in Japan. Could we sponsor A Day in the Life of Japan? And so, I never went back to shooting.

“I could not have done all this without the help of two people—David Cohen and my wife, Jennifer Erwitt. My longtime business partner on Day in the Life and 24/7 projects was David Cohen, and we problem-solved on all projects together. We are still close friends to this day. My wife, Jennifer Erwitt, came on board the Day in the Life projects in 1983 with our second book, A Day in the Life of Hawaii, and has been my partner and co-author on all projects at Against All Odds Productions, beginning with The Power to Heal through The Good Fight.

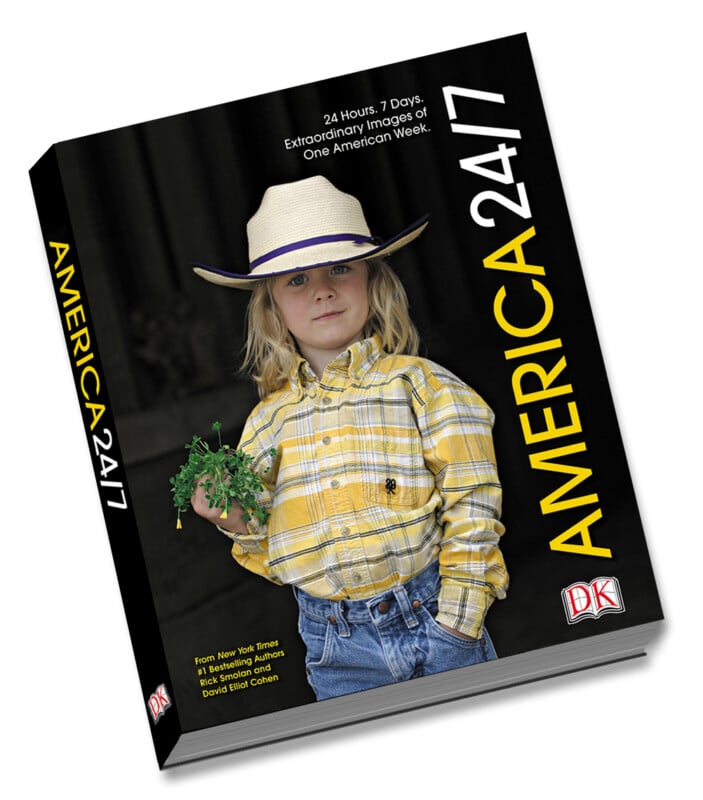

“We started making a one-hour movie about how we did the book, and then we started putting up exhibits. And then when CDs came out, we started doing interactive CDs that came with the book. When everybody and their brother had a cell phone in their pocket, we did America 24/7, inviting the public to participate. We had 2,000 photographers, but 25,000 members of the public were also shooting.

“Everybody could get the book, and then you could order a copy with your own [photo on a] wrap-around dust jacket. IKEA commissioned us to do two books. About the concept of home, no IKEA products. But just what in the world does home mean? Paul McCartney wrote the introduction to the book in England, and Matt Groening of The Simpsons wrote the introduction to America at Home. With each of our books, we keep adding technology.

Keeping the Excitement Alive in Book Publishing

“After doing the 10th Day in Life book, it got to be a bit old, like it felt I’d solved the same problem over and over again in different countries, and it wasn’t as exciting,” says the book maker. “I was a little jaded because every book we did became the number one book in that country, and it was sort of a formula that now wasn’t really as exciting as it was at the beginning, or scary. I’m better when I’m a little scared.

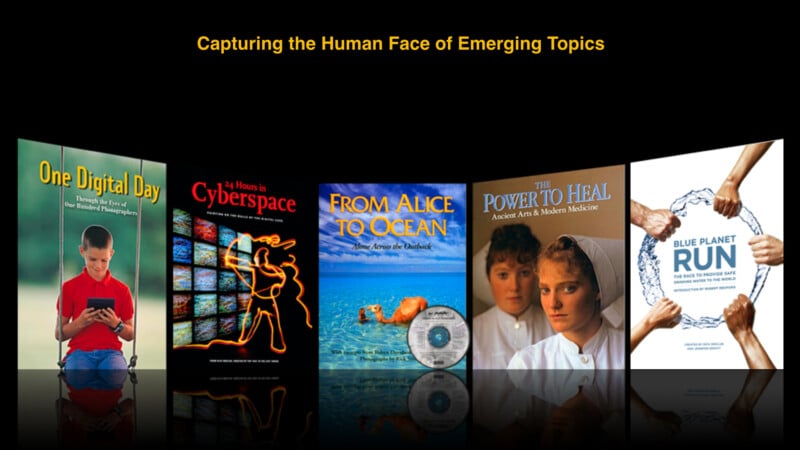

“My father said, ‘Why don’t you do a book with the world of medicine, how the human race is learning to heal itself?’ And so, we did a book called The Power to Heal: Ancient Arts & Modern Medicine. We had 100 photographers worldwide for a week, and one in three doctors in America received a free copy from 11 drug companies. We raised $5 million in two weeks from 11 drug companies. It has dwarfed everything we ever raised for the Day in Life books.

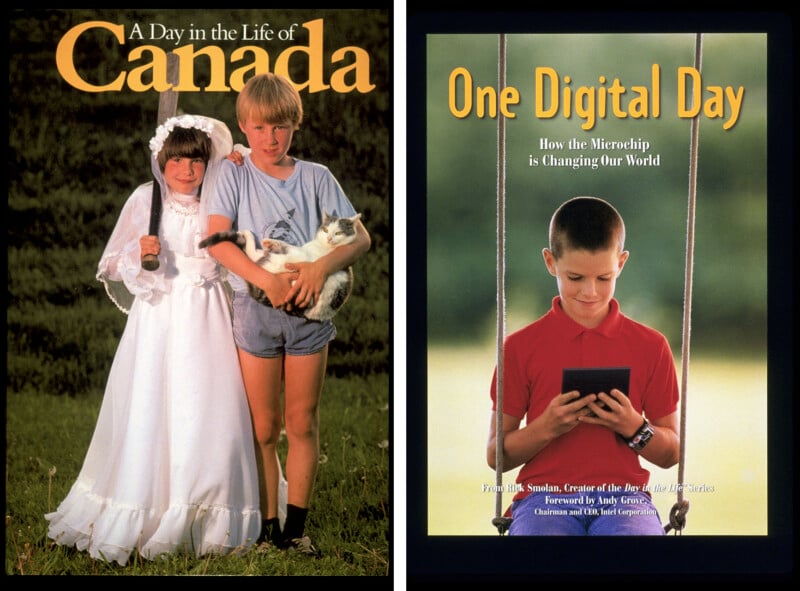

And so, my father set me on a new path. He said, instead of a broad look at a country, what if you do a deep dive? Then we did 24 Hours in Cyberspace. I spoke at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Andy Grove [CEO of Intel] came up to me after my talk and said, ‘Would you do a book about the microprocessor? And I said, I don’t do annual reports. I’m a journalist. And he said, ‘Well, what if it wasn’t about Intel? How many times do you think a microprocessor touches your life in a day? And I said, two or three, you know, go to the bank to get money out. He said, ’32 times. Your car wouldn’t start, and you couldn’t transfer money. You could not make a phone call. These little chips, over the last 30 years, have crept into the background, secretly, quietly into cars, into every aspect of our lives.’ And so, we did a book. One Digital Day: How the Microchip is Changing Our World. It was on the cover of Fortune magazine. It was the most extensive excerpt in Fortune’s history.

“Next, we did Blue Planet Run: The Race to Provide Safe Drinking Water to the world and The Human Face of Big Data. And then, most recently, we did a book about the history of social justice through the eyes of photographers, The Good Fight: America’s Ongoing Struggle for Justice. With every book, we’ve added this sort of technology hook. There are custom covers, smartphone-enabled books, and whatever else. So that’s been our motto. We never let sponsors exercise any editorial control, but we use their resources to promote and publicize the book. We’ve been fortunate. Every book we’ve done has been an enormous success.

“I reached out to all my friends who’ve been on the campaign trail [with Obama], and I said, ‘Do you have pictures that were never published that you shot while you were covering him? We got 40,000 pictures from photographers who had been on the campaign trail. And that was the Obama Time Capsule.

“We’ve done 80 books. Because of the American 24/7 Series, we did every single state in one year. We did 50 books in one year, which is stupid.

Smolan has often been ahead of the technology curve

“We also paid everybody with Macintoshes,” says Smolan after a bit of thinking. “When we did A Day in the Life of Japan, Apple gave us office space, and Steve Jobs came over one day without knowing about it. And at first, he was kind of like, ‘Who let these people in here?’ And then we spoke to him, and I said, ‘Look, we have $1,000 to pay every photographer for A Day in the Life of Japan. Could we buy Macintoshes for everybody?’ which were then costing $3,000 for Macintosh, printer, and software. And so, we worked out a deal with Apple. We probably went through almost 1000 Macs [over different books] for all the editors and photographers.

“We’re the first ones to put a CD-ROM into a book. We’re the first to mass-customize a New York Times bestseller [with your photos on the dust jacket]. We were the first to do smartphone-enabled books where you point your phone at a picture in the book, and it plays the TED Talk. [We started] Photo One in 1980-81, where we created a worldwide network for photographers. But it was too early in the process.

From Alice to Ocean got a tremendous amount of attention because it was the first book to come with a CD, or actually two CD-ROMS. Kodak and Apple sponsored the book, and Apple bundled the CD with 500,000 Macintoshes. Every Macintosh sold that year came with our CD. It got attention not just from the book world, but also from the technology and media worlds — everyone from the Wall Street Journal to the New York Times. The publicity for that book was incredible because it was sort of a merging of the book and the CD-ROM. And then, a year later, we published a book called Passage to Vietnam, which also had links to the internet. And there was an interactive CD that also won the top interactive media awards that year.

“We did a book called 24 Hours in Cyberspace. We worked out a deal with Jeff Bezos at Amazon that allowed people to order the book and upload their own pictures. And so, you were the co-author of the book. Your picture appeared next to Oprah Winfrey on page 32, and the invitation to attend Obama’s inauguration [in The Obama Time Capsule, 2009] bore your name, making it the first best-selling, mass-customized book in history. We kept trying to add more to it.

In the last three books we’ve done, you can point your phone at a photograph, and it streams a YouTube video, a documentary, or whatever.

From Photography to Books to TV Serials

“I’m doing a Netflix TV science fiction series right now, Tunnel in the Sky,” he says with excitement in his voice. It’s my favorite Robert A. Heinlein book since I was 16. I have Guillermo del Toro’s [3 Academy Award Winner] creative partner, J. Miles Dale, as my producer–so Miles and I and the show runner, who did Fear the Walking Dead. I own the book, and I brought them into the picture. The three of us pitched Apple, Hulu, Amazon, Disney, and Netflix, and we chose Netflix because my partners have worked with it before.

“It’s going to be a TV series, and we hope it’ll be three years, three seasons. And I don’t know anything. It’s a brand-new world. I’ve done documentaries; I’ve never done scripted before. Imagine Grand Central Station, and every train track is a wormhole to someplace else in the galaxy. And Earth has become very polluted.

“And so every year they have a contest for 100 teenagers. The best teenagers on earth get to colonize new planets. And the graduation exercise before you get a planet is sending the 100 kids to one planet for a week. You take one weapon. They don’t want the kids to die, but they want to weed out the ones who aren’t the smartest, brightest, or most adaptable. It’s like Lost in Space meets Lord of the Flies, showing how these children build a new society. It’s not dystopian. There’s a lot of conflict, but it’s hopeful.

“So, when I was 16, I met Elliot, or no, when I was 16, I saw Elliot’s work for the first time [which led to my photography career], and when I was 16, I read this book. So, 16 was a very formative year.

“…And that’s my long, boring story.”

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.