“I have lots of colleagues who think this is a bad idea. Even doing the research.”

Would you use technology to try to repair disappearing Arctic sea ice?

Some scientists at one of North America’s biggest climate conferences increasingly think this may be the only way forward – or at least, it deserves much more examination.

“I get their point,” Brendan Kelly said of his colleagues who don’t like that idea. “Most of the things that give them anxiety give me anxiety. My sense is therefore we should do the research. What we don’t know is what can hurt us.”

Kelly is not a fringe participant at ArcticNet, the conference being held in Calgary this week. He chairs the ArcticNet board and is chief scientist for the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He has worked in the Arctic for nearly half a century.

On Monday, he led a panel in which scientists studying sea ice discussed how technology could help.

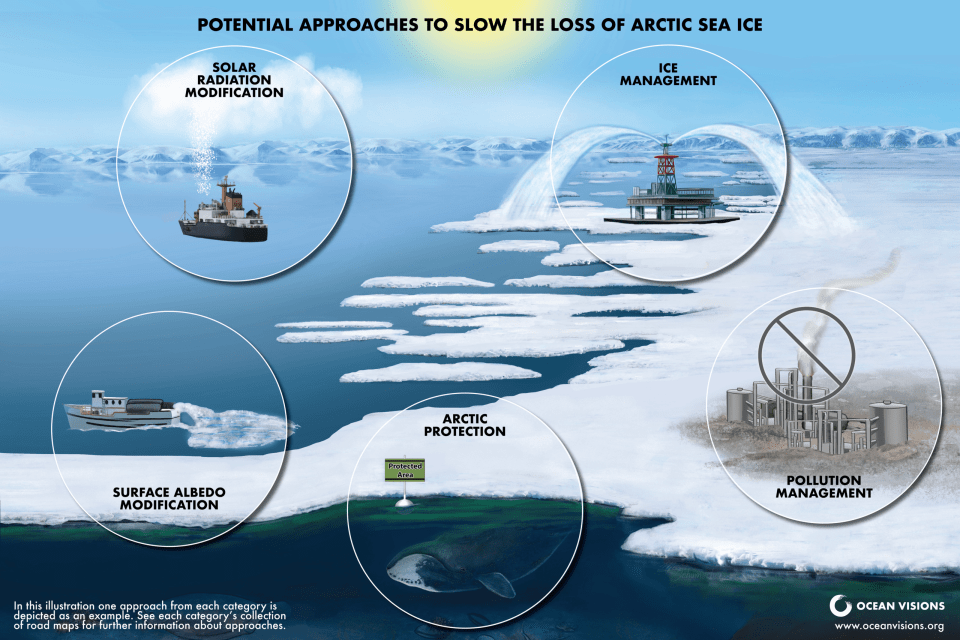

“That could involve all sorts of proposed approaches that people have thrown out,” said Bridget Shayka of Ocean Visions, an American non-profit trying to communicate the severity of the issue and some of the options.

Those approaches could be anything from pumping seawater up from below to thicken sea ice “all the way to atmospheric approaches that might limit some of the sunlight and prevent the Arctic from heating up so quickly,” Shayka said.

An Ocean Visions graphic shows potential ways of repairing sea ice. The word “albedo” refers to how much sunlight a surface reflects.

An Ocean Visions graphic shows potential ways of repairing sea ice. The word “albedo” refers to how much sunlight a surface reflects.

To reach the scale needed to make a significant impact, these would be huge projects.

For decades, scientists have balked at that kind of intervention in part through fear that the consequences may not be fully understood – and could be as worrisome as the damage humans have already done through pollution.

Kelly said the answer should be learning more about those consequences.

“Some billionaire, maybe the richest man in the world, might decide unilaterally: ‘I’m going to do one of these things.’ Could be in the atmosphere, could be in the sea, could be on the ice,” he said.

“If we don’t have a good understanding of what the consequences could be – in other words, we have done the research with local people – we’ll have no tools with which to try to stop such an effort, if that’s what’s warranted.

“We have to harness what Inuit know, and we have to harness what climate modellers know and sea ice ecologists. I would argue we have the information but it is buried. It’s buried in oral tradition and hence not available to decision-makers in the Inuit community, and it’s buried in scientific jargon in the science community.”

Why has it come to this?

Research into the state of Arctic sea ice makes for bleak reading.

There is a consensus that the Arctic is warming about four times faster than other parts of the planet. The latest research projects the Arctic could see its first ice-free September as early as the 2050s or even the 2030s, depending on emissions levels.

Meanwhile, the reflectivity of Arctic sea ice helps prevent global warming. The less sea ice we have, the worse the warming gets.

Another consensus is that the number-one fix would be reducing emissions. Without a major change in emissions, scientists said on Monday, climate engineering will probably just noodle around the edges of a much bigger problem.

Even so, some trials of this technology already exist.

Real Ice, a British startup for which Kelly serves as an advisor, describes its work as “encouraging the natural process of Arctic sea ice generation.”

It plans to do so by pumping seawater onto the ice surface using underwater drones powered by hydrogen.

“At the beginning of winter, we will flood the sea ice with seawater to create an extra layer of sea ice and remove the insulating snow layer,” Real Ice explains on its website.

“At the end of winter, we will re-create the snow layer to protect the sea ice from solar radiations, helping it last longer through the summer months.”

A Real Ice video about its Cambridge Bay tests. (It’ll start midway through, where the video shows seawater being pumped onto the ice.)

At ArcticNet on Monday, Real Ice co-chief executive Andrea Ceccolini said his company is trying to answer three questions: whether this approach is going to work, whether there are “ecological or societal” impacts, and whether it can scale up “to Arctic scale.”

Real Ice has run tests in Alaska and Nunavut, experimenting over several winters on small areas of ice around Cambridge Bay.

“We saw that towards the end of the melt season, our ice was still much thicker than the control areas of the ice that we didn’t treat,” Ceccolini said.

“The other expectation that we started to validate is that when we come into the melt season, our sea ice will also be brighter and so reflect much more radiation back into space and keep the region cooler.”

That presumption is still being tested, he added, as is whether this method can work at scale.

Kelly said overall research into these technologies lags behind most of our Arctic climate knowledge. If our current overall Arctic climate research stands at a 6/10, he said, sea ice climate engineering is a 2/10.

“I’m trying to get this conversation going across the Arctic,” he said. “We have a long ways to go.”

‘We don’t need to thicken the whole Arctic’

At the same time as scientists in a Calgary conference centre figure out how (and whether) to rebuild sea ice, others want the ice to go away.

Increasingly, shipping firms see the Northwest Passage as a viable option because sea ice cover is shrinking. That comes with potential economic benefits as well as a growing likelihood of environmental disaster.

This was illustrated in the summer when a Dutch cargo vessel became stranded in a strait off the coast of Nunavut, prompting a race to free it before the sea ice set in. Ultimately, no crew members were hurt and no pollution was reported to have reached the surrounding environment.

More: What should we learn from another Northwest Passage close call?

This contrast is not lost on residents of Arctic coastal communities, who see an Arctic Ocean dotted with cruise ships and container vessels even as scientists arrive in town to repair the sea ice.

Cyrus Harris grew up in and near Kotzebue, on Alaska’s west coast.

Describing sea ice as important to survival in that region, Harris said on Monday there are 100 words to describe different forms of ice. “They all have a purpose,” he said.

“But the minute you get ice, here comes the icebreaker and damages it all.”

Thamesborg – a freighter that became stranded in the Northwest Passage this summer – is seen in an image published by Wagenborg in 2020.

Thamesborg – a freighter that became stranded in the Northwest Passage this summer – is seen in an image published by Wagenborg in 2020.

Views differ on how to handle the relationship between sea ice repair and increased Arctic shipping.

“We are discussing a world that involves people looking forward to having shipping lanes in the Arctic. It’s inevitable,” Ceccolini said.

“So many countries are coming forward – Japan, China, Russia. They want to be able to move stuff across the Arctic.

“I don’t think ice thickening should necessarily interfere with that. The Arctic is also very big. There will be areas where we thicken up the ice and, at the same time, have dedicated shipping lanes for commerce. The two things can survive. We don’t need to thicken up the whole Arctic. It would be impossible.”

Others at Monday’s session worried that if Arctic shipping is seen as an issue of economic opportunity and sovereignty, people communicating the impact on communities risk being seen as “in the way.”

“Some countries are looking forward to the ice disappearing,” said Shayka. “That means we need to be even more proactive about: what can we do?

“If some countries are saying ‘we don’t need to worry about this right now,’ then that means it’s actually more urgent. We should be learning what we can and figuring out if there’s anything we can do to prolong ice a little longer.”

Bailing out a sinking boat

Sea ice sessions will run throughout the week at ArcticNet, which closes on Thursday evening.

Multiple groups will set out their approaches to climate engineering. The prevailing theme on Monday? There is interest in seeing how these techniques might work, but realism about the dangers of deploying any of them at scale.

Another issue the sessions tackle is who ought to decide which technological options, if any, are ultimately deployed.

A group named Cooling Conversations, in attendance at ArcticNet, has a mission to “speak to the people who are at the centre of these conversations, or should be at the centre of these conversations but perhaps haven’t been.”

Cooling Conversations’ Albert Van Wijngaarden has argued that climate engineering’s practical implications require a nuanced discussion that heavily involves people who live in the Arctic. The team has so far been to northern Scandinavia, Greenland and Iceland.

“We’ve been trying to speak to as many people as possible about what they think is important around these technologies and how we can improve these conversations,” he told Monday’s session at ArcticNet.

“So far, a lot of the conversations around these technologies have been had at a top-down level with assumptions from scientists. But we want to take a step back,” he said, and have “a conversation about the conversation.”

Multiple Indigenous people in Monday’s session described having their concenrs about sea ice or the local environment ignored for years.

“That really sums up who has been deciding,” said Shayka at Ocean Visions, “and it’s people who are not listening to all of the important information and perspectives around the world.”

An image of Brendan Kelly published to the website of Search, the Study of Environmental Arctic Change at the University of Alaska.

An image of Brendan Kelly published to the website of Search, the Study of Environmental Arctic Change at the University of Alaska.

Kelly said humanity’s ongoing failure to control its emissions makes it hard not to be pessimistic about the future, with or without options like climate engineering.

“I don’t want to look people in the eye and say, ‘Oh, it’s all great. We can do this. We’ve got this.’ We don’t have this,” he said.

But he compares the Earth’s current status to that of a sinking boat. If the boat is sinking, he said, you examine any solution and try to collaborate.

“You’re bailing and bailing, and you can see the water is coming in faster than you’re bailing, but you’re not going to stop bailing,” Kelly said.

“The chances I’m going to succeed might be really low but the consequences of not succeeding are extremely high.

“If I’ve got everybody on the boat bailing, maybe – just maybe – we keep this thing from going down.”

Related Articles