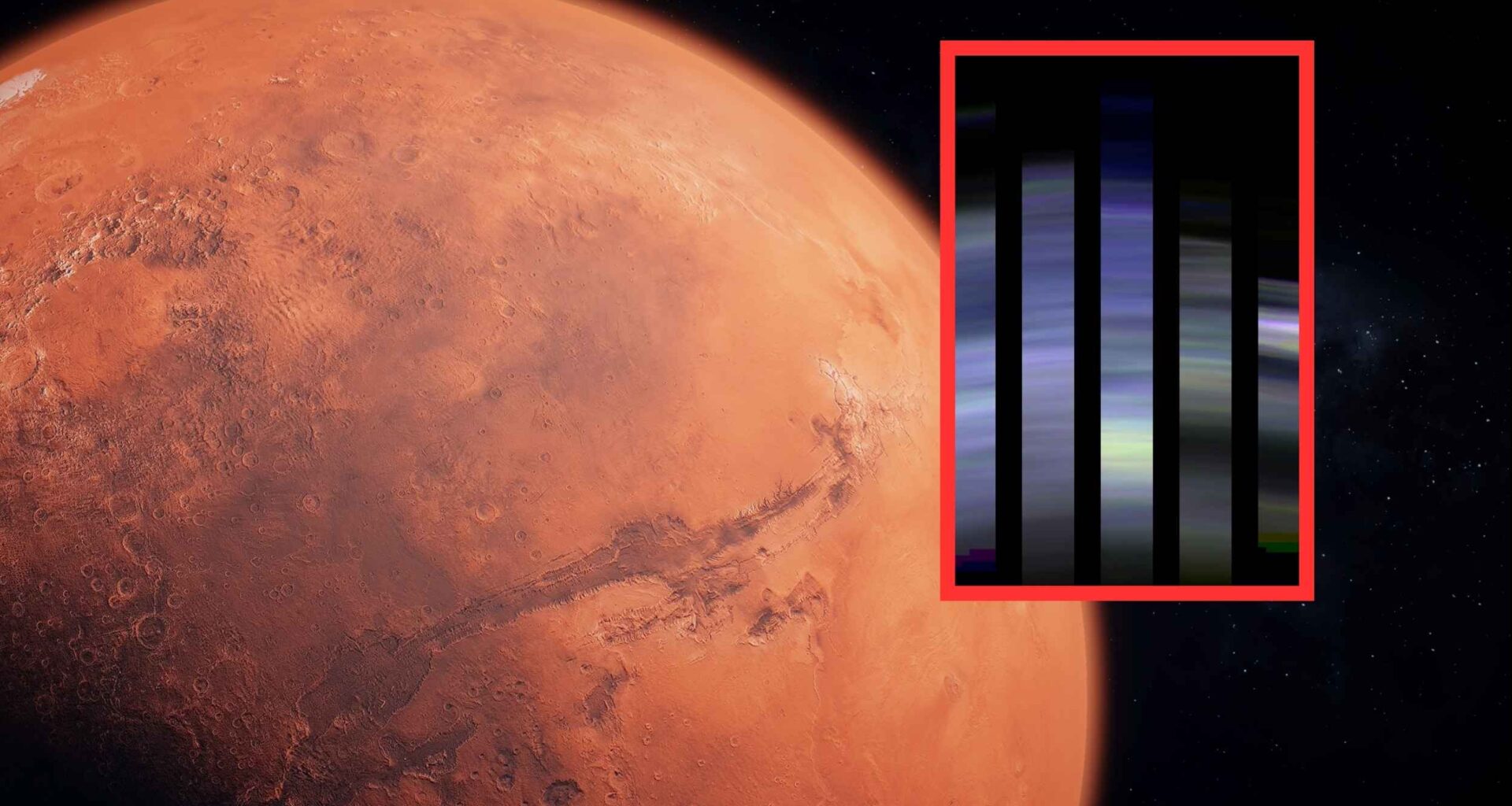

At sunset on January 21, 2024, a European orbiter captured the curved edge of Mars as seen against empty space, glowing with dozens of razor-thin layers.

The images resolve the atmosphere at 59 feet (18 meters) per pixel, according to a new study. ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) flew about 250 miles (400 kilometers) above Terra Cimmeria in the southern highlands, and looked back through twilight.

Its Color and Stereo Surface Imaging System, or CaSSIS, viewed the Martian atmosphere from the planet’s shadow, where backlit layers stand out crisply.

Sunset on Mars

Five narrow, vertical slices, each about 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers) wide, captured the atmosphere’s layered structure at twilight.

The layers repeat from roughly 9 to 34 miles (14 to 56 kilometers) in altitude, showing changes in brightness and subtle shifts in color.

The work was led by Nicolas Thomas, CaSSIS principal investigator, at the University of Bern. His research focuses on high-precision planetary imaging and the physics of dusty sunsets on Mars.

The camera discerns sub-mile structures and records about 20 percent swings in color within individual sheets of haze.

It also measures I/F, a brightness scaled by the incoming sunlight, that climbs near one in this geometry.

Martian sunset geometry

Twilight puts dust between the Sun and the camera in a forward scattering configuration – light deflected mostly in its original direction – that amplifies brightness.

That trick prefers blue wavelengths, which become more concentrated near the Sun, compared with reds that are spread wider across the sky.

“When the blue light scatters off the dust, it stays closer to the direction of the Sun,” said Mark Lemmon, a Curiosity scientist. A NASA resource explains why this happens and documents rover views of blue sunsets on Mars.

Layers, colors, and particle sizes

Color ratios trend toward blue with height, suggesting that aerosols, tiny suspended particles like dust or ice, shrink as altitude increases.

Above roughly 27 miles (43 kilometers), some layers redden again, hinting at shifting compositions and sizes inside the higher atmosphere.

The team also spotted delicate layers in the mesosphere, the cold middle layer of an atmosphere, hovering between about 29 and 35 miles (46 and 56 kilometers).

These detached sheets sit above a bulge of brightness around 25 miles (40 kilometers), a feature that models will need to explain carefully.

Below this height, the layers likely hold dust lofted from the surface, while higher sheets may include tiny water ice grains.

Color changes track particle radius, the average size of the grains, which decreases steadily with height in most profiles.

How CaSSIS got these images

To make these scans, CaSSIS rotated its detector to sweep the limb while the spacecraft cruised at about 2 miles per second (3.2 kilometers per second).

The geometry sat near a phase angle, the angle between the Sun, the object, and the observer in space, of roughly 174 degrees, which is ideal for bright forward scattering.

Five, well-exposed datasets were collected every 124 miles (200 kilometers) along the ground track during a four minute window over southern Terra Cimmeria.

Each image spanned about 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers) across the limb, allowing near continuous sampling of the stacked sheets.

CaSSIS delivers targeted color imaging with about 15 feet (4.5 meters) per pixel detail for surface science. For the limb sequence, the team pushed sensitivity and timing to track thin atmospheric sheets instead of ground textures.

Mars climate clue

Past Mars Climate Sounder profiles show seasonal dust heights and common ice caps above haze, in a complementary report.

The new layering snapshots give modelers a sharper target for how particles stack during calm periods and during stormy weeks.

Mars does not keep a fixed atmosphere, because dust lifting changes with the season and with the intensity of sunlight.

That variability makes vertical layering more than a pretty picture, because it anchors climate models to real heights and colors.

Robotic explorers depend on light and temperature, so knowing how dust and ice stack at sunset clarifies operational planning.

These snapshots also help bridge measurements from orbit with sky observations gathered by landers and rovers on the ground.

Future plans for Mars

ESA plans to repeat these limb observations about once per month to build a long baseline of twilight data.

A seasonal atlas of layers could test whether the current pattern holds or twists under the stress of regional storms.

Scientists will ask why some layers turn red aloft, whether composition shifts explain the change, and how particle sizes evolve over latitude.

They will track the texture from equator to pole to see when the layers thicken, thin, or separate into detached sheets.

For now, the conclusion is simple, because Mars hides more than a red sky at sunset and reveals a precise, layered climate.

With monthly views and careful modeling, those layers will turn into measurements that pin down particle sizes, textures, and motions through the evening air.

The full study is published in Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–