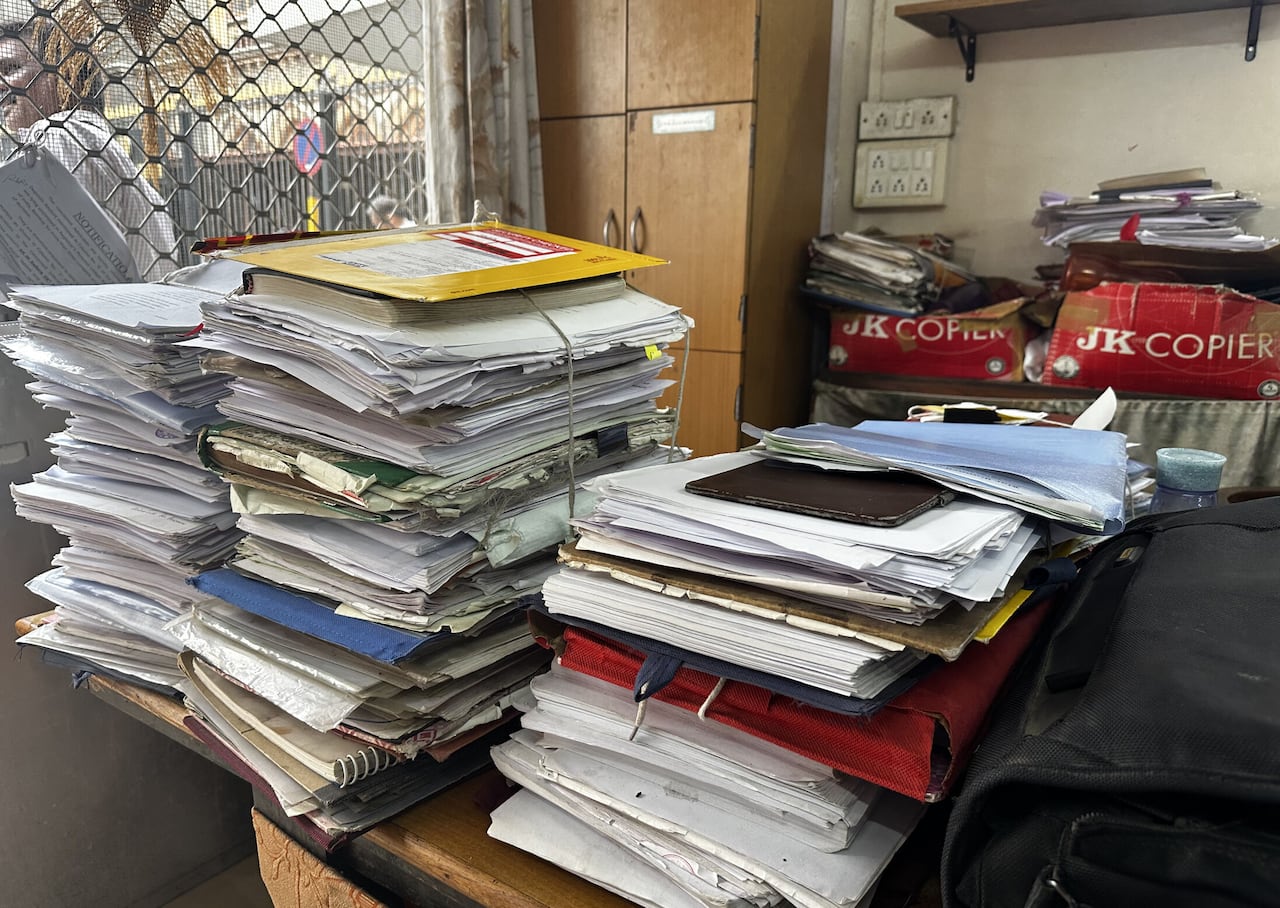

The frustration and weariness crept into Sanjay Goel’s voice as he stared at the giant stack of handwritten court documents in front of him.

He was on one of his countless visits from Vancouver to Mumbai, India, to fight for justice in the brutal killing of his mother and was struggling to describe the excruciating delays in criminal court proceedings.

“It’s beyond my comprehension,” Goel, 61, told CBC News.

“Files have disappeared. Files have been found months later.”

His mother, Dr. Asha Goel, a Canadian citizen, was visiting family in Mumbai when she was badly beaten and killed in 2003 in an attack allegedly ordered by two of her brothers.

Her children initially thought the criminal case would be open and shut. They had a confession from one of the alleged assailants, as well as strong DNA evidence where the match is for one person out of 10 billion.

But even all that evidence couldn’t penetrate India’s massively overburdened justice system, where more than 54 million cases, criminal and civil, are pending.

Lawyers go through a case file inside their chamber at the court complex in Ghaziabad, India, on Sept. 6, 2024. (Money Sharma/AFP/Getty Images)

Lawyers go through a case file inside their chamber at the court complex in Ghaziabad, India, on Sept. 6, 2024. (Money Sharma/AFP/Getty Images)

Goel, his sisters and his elderly father are waiting for a verdict after hundreds of court hearings and oral proceedings, with some witnesses now deceased and others too old or impaired to testify.

“It’s like Groundhog Day,” Goel said. “The judge has to dismiss or render a decision more than once on the same argument.”

Many lawyers and judges forced to navigate India’s archaic judicial system are afflicted with an equal sense of hopelessness.

‘Monumental’ backlog

“There is desperation,” said Gautam Patel, a recently retired Bombay High Court judge.

The backlog “has become so monumental, I think we’re pretty much in panic mode.”

The numbers are staggering, even for a country of 1.4 billion.

At last count, more than 54 million cases are pending across the country, according to the National Judicial Data Grid.

The backlog has doubled in the past decade, with more than 5.5 million lawsuits that have dragged on for upwards of 10 years.

In early 2023, the country’s oldest pending case, a bank liquidation lawsuit filed in November 1948, was disposed of for the most pedantic of reasons — nobody showed up to the last hearing scheduled.

Stacks of court documents pile up at the Bombay High Court. (Ayushi Shah)

Stacks of court documents pile up at the Bombay High Court. (Ayushi Shah)

The rate at which new cases are filed in India’s courts is higher than the bench’s capacity to issue judgments. At the current pace, experts say it would take several hundred years to clear the docket completely — and many believe resolving cases more quickly doesn’t seem to be a priority.

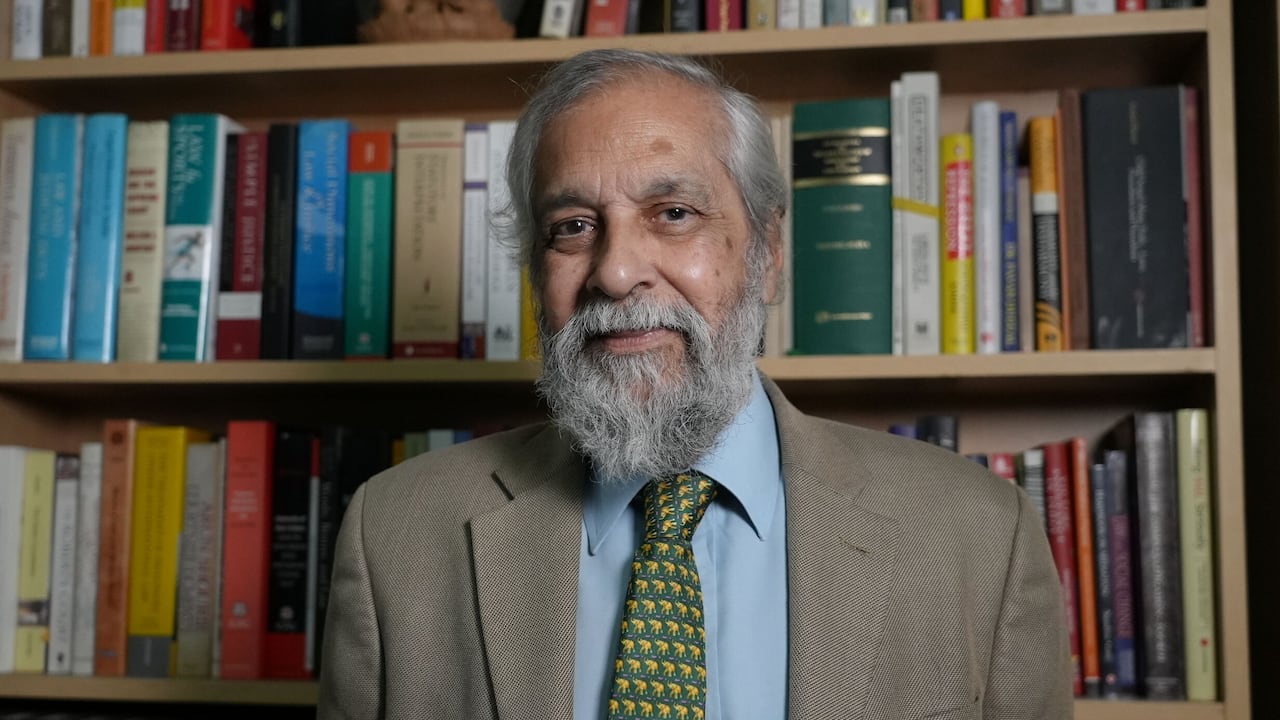

“No serious attempt has been made to try and tackle the backlog,” retired Supreme Court judge Madan Lokur said during an interview at his home in Delhi.

The situation is so dire that then chief justice of India’s Supreme Court, Tirath Singh Thakur, broke down and seemed on the verge of tears during a speech to the country’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, over what he called an “avalanche” of cases, as he pleaded with the government to recruit more judges to tackle the backlog.

That was in 2016, when the number of pending cases was around 27 million — half of what the backlog is now.

The government is India’s biggest litigant, involved in roughly half the cases that are wending their way through the system.

Successive governments have promised to tackle the persistent issue, with little dent made on the country’s massive logjam of pending cases.

‘When will the whole ordeal end?’

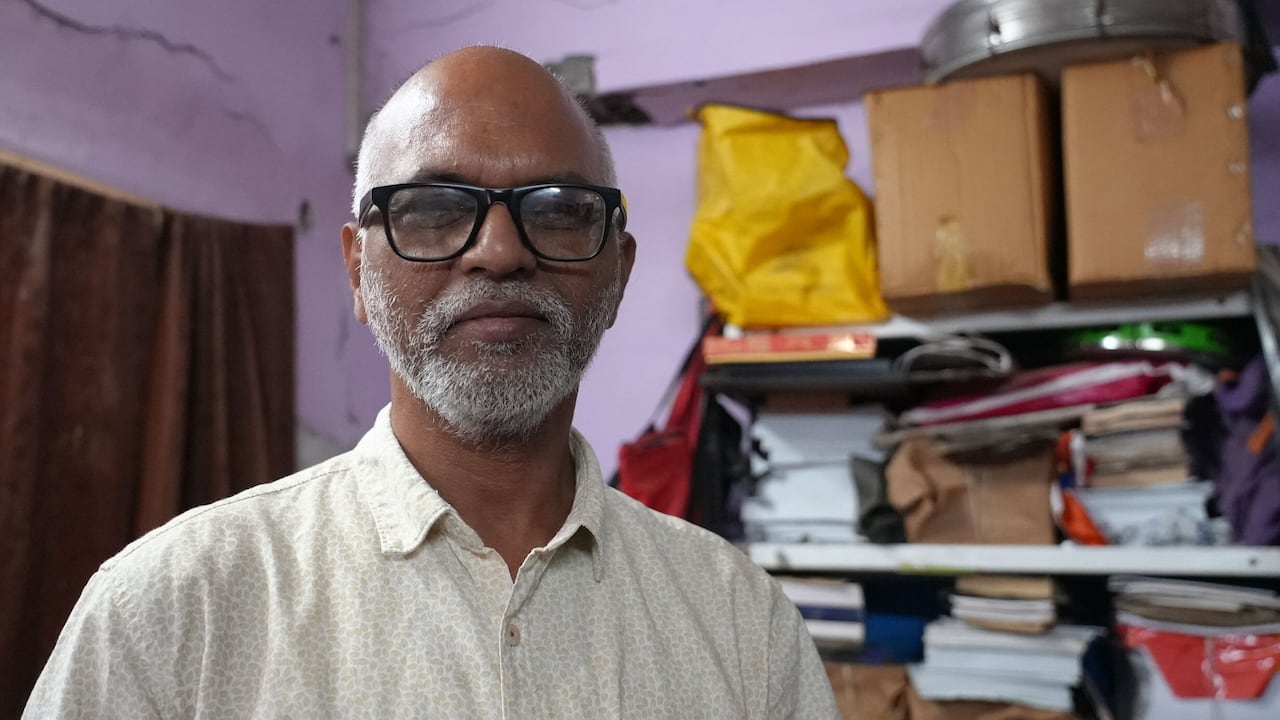

Mumbai activist Sudhir Dhawale is familiar with the pain of waiting for a judgment.

He sat in jail for 6½ years, two of which were in solitary confinement, waiting for bail.

Dhawale was arrested in June 2018 on charges of inciting caste violence, under India’s highly controversial Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), an anti-terrorism law that has been criticized for its vague definitions of criminal activity and strict bail conditions.

Sudhir Dhawale, an activist in Mumbai, spent more than six years in jail waiting for bail. His trial is still pending. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Sudhir Dhawale, an activist in Mumbai, spent more than six years in jail waiting for bail. His trial is still pending. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

“In jail … all people do is wait and wait,” he said. “When will the whole ordeal end? Nobody knows.”

Dhawale, who has spent years demonstrating against caste discrimination in India, found the scale of charges against him shocking.

“The charge sheet is 25,000 pages long. There are more than 350 witnesses,” he told CBC News, adding that prosecutors didn’t appear to know how to frame the charges against him and 15 other academics and activists arrested at the same time.

When he got bail, a judge at the Bombay High Court ruled that Dhawale had suffered an “inordinate delay” that violated his fundamental right to a speedy trial.

Nearly a year after his release, he is still waiting for a trial date.

Procedures compound backlog

A key issue that compounded the backlog is that India’s judicial system, inherited from the British, is rigid and has archaic procedures that rely heavily on oral arguments from lawyers, who also produce lengthy written submissions that tread similar territory.

India’s Supreme Court announced in December that in 2026, it will move to restrict oral arguments to a maximum of 15 minutes, the first attempt to impose a time limit, but Lokur said lawyers “need to be on board” for the limits to work.

Witness testimonies are often written by hand and hard to decipher. Court stenographers have to transcribe all of it, slowing the process down further.

India is also plagued with a shortage of judges, with a ratio of 15 judges for every million Indians, according to data compiled by the India Justice Report, a non-profit organization. In Canada, federal and provincial court data shows there are roughly 65 judges per million people.

Retired Supreme Court justice Madan Lokur says here has been no serious attempt to tackle India’s staggering judicial backlog. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Retired Supreme Court justice Madan Lokur says here has been no serious attempt to tackle India’s staggering judicial backlog. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Lokur, the retired Supreme Court justice, said vacancies hover at around 40 per cent for India’s high court and roughly 20 per cent in lower courts.

“Recommendations [for judge appointments] are not being made on time,” he said, and even if they are eventually made, “the vacancies are not being filled up.”

Another main issue, according to the experienced judge who is serving as chairperson for the United Nations Internal Justice Council, is cases that shouldn’t end up in court, such as bouncing a cheque because of insufficient funds.

In Canada, it’s punishable by a bank fee, but in India, bouncing a cheque is a criminal offence that could land the person who wrote the cheque in jail for up to two years.

“There are hundreds of thousands of such cases that are pending,” Lokur said. “At one point in time, there were almost 1,000 cases [of bounced cheques] being filed in a day in Delhi.”

Bail applications are also exploding, said Patel, the former judge at Bombay’s High Court.

“There are high courts in this country that have 300 new bail applications a day,” he said. “That’s an insane number.”

WATCH | Waiting decades for justice:

Why India’s courts are drowning in 52 million cases

India’s courts are struggling under a massive backlog of cases that would take hundreds of years to clear. CBC’s South Asia correspondent Salimah Shivji explains how the problem got so bad and hears from people who have been waiting decades for justice.

Patel told CBC News it’s hard to start to tackle the issues with India’s judicial system because the archaic systems are so ingrained, recalling for example one case that landed on his desk.

“By the time it came to me, 17 judges had decided the same question of law in exactly the same manner,” he said.

“I was the 18th in a row and they were still saying the same thing that they’d done on Day 1. What a colossal waste of time this is.”

India’s Supreme Court says that in 2026, it will move to restrict oral arguments in cases it hears to a maximum of 15 minutes. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

India’s Supreme Court says that in 2026, it will move to restrict oral arguments in cases it hears to a maximum of 15 minutes. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

It’s a loss of productivity as well. A study from legal think-tank DAKSH estimates lost wages and business that come from attending court hearings amount to nearly 0.5 per cent of India’s GDP.

Patel said a potential solution is to outsource some of the court’s administrative work to management specialists.

He’s also been playing around with generative artificial intelligence, in the form of a new program called Adalat AI, which he said “saves an incredible amount of time.”

It transcribes court proceedings in real time and several languages, eliminating the work of stenographers. The program is slowly spreading and the company says it is used in more than 2,000 district courts in eight Indian states.

When Patel heard about it, his reaction was simple.

“Where have you been all my life?”

‘I’m trying my best’

But for Sanjay Goel, incremental steps to address India’s overburdened courts don’t change his reality — that justice has not been served, it’s been “buried in bureaucracy.”

He said he feels lucky he and his family have the means to keep fighting to see his mother’s killers behind bars.

“I’m trying my best,” he told CBC News. “But it’s tiring.”

Sanjay Goel, left, and his mother, Dr. Asha Goel, right, are shown in an undated photo. (Submitted by Sanjay Goel)

Sanjay Goel, left, and his mother, Dr. Asha Goel, right, are shown in an undated photo. (Submitted by Sanjay Goel)

He’s disappointed that Canadian government officials have “washed their hands of this matter,” he said, even though his mother lived and worked as an obstetrician in Canada for four decades and her brother, who is wanted by Indian police in connection with the killing, is also a Canadian citizen now living in the Toronto area.

But mostly, it pains him to think of his father, widowed and alone at 88.

“It’s hard to look at him. I’d say, ‘Dad, I’ve done what’s expected,'” Goel said, tears in his eyes, his voice quivering.

“I made a promise and I need to fulfil that promise, as best I can.”